The wooden box had three metallic wheels.

It looked like a toy, or perhaps a piece of scrap assembled in a garage, but the man holding it believed it was the key to the human mind.

It was December 9, 1968.

In the cavernous Brooks Hall in San Francisco, more than a thousand of the world’s top computer scientists sat in folding chairs, waiting. They were used to the roar of air conditioning units cooling massive mainframes. They were used to the smell of ozone and the stack of stiff paper punch cards that defined their working lives.

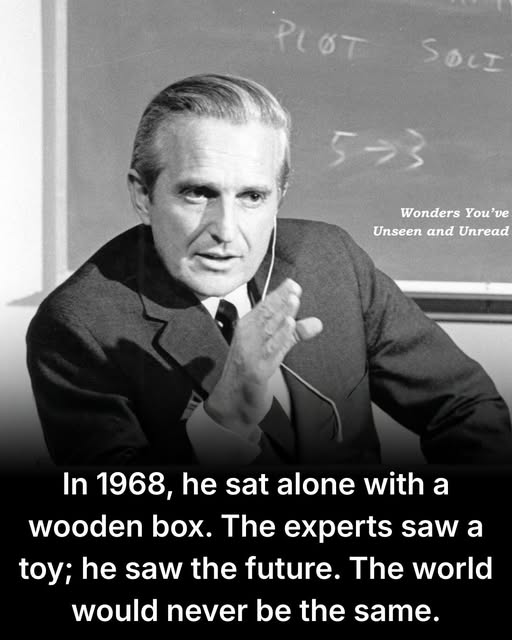

They were not used to Douglas Engelbart.

He sat alone on the stage, wearing a headset that looked like it belonged to a pilot, staring at a screen that flickered with a ghostly green light. Behind the scenes, a team of engineers held their breath, praying that the delicate web of wires and microwave signals they had cobbled together would hold for just ninety minutes.

If it worked, it would change how humanity thought.

If it failed, Douglas Engelbart would simply be the man who wasted millions of taxpayer dollars on a fantasy.

The world of 1968 was analog.

Information lived on paper. If you wanted to change a paragraph in a report, you retyped the entire page. If you wanted to send a document to a colleague in another city, you put it in an envelope and waited three days. If you wanted to calculate a trajectory, you gave a stack of cards to an operator, who fed them into a machine the size of a room, and you came back the next day for the results.

Computers were calculators. They were powerful, loud, and distant. They were owned by institutions, guarded by specialists, and kept behind glass walls. The idea that a single person would sit in front of a screen and “interact” with a computer in real-time was not just technically difficult; it was culturally absurd.

Engelbart, a soft-spoken engineer from Oregon, saw it differently.

He had grown up in the Depression, fixing water pumps and electrical lines. He understood tools. He believed that the problems facing humanity—war, poverty, disease—were becoming too complex for the unassisted human brain to solve. We needed better tools. We needed to “augment human intellect.”

For years, he had run a lab at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). While others focused on making computers faster at math, Engelbart’s team focused on making them responsive. They built systems that allowed a user to point, click, and see results instantly.

They called their system NLS, or the “oN-Line System.”

It was a radical departure from the status quo. To the establishment, computing was serious business involving batch processing and efficiency. Engelbart was talking about “manipulating symbols” and “collaboration.”

The pressure on Engelbart was immense.

The funding for his Augmentation Research Center came from ARPA (the Advanced Research Projects Agency), the same government body responsible for military technology. They had poured significant resources into his vision, but results were hard to quantify. There were no enemy codes broken, no missile trajectories calculated. Just a group of men in California moving text around on a screen.

The critics were loud. They called him a dreamer. They said his ideas were “pie in the sky.” Why would anyone need to see a document on a screen when typewriters worked perfectly fine? Why would anyone need to point at data?

This presentation was his answer.

It was an all-or-nothing gamble.

To make the demonstration work, Engelbart wasn’t just using a computer on the stage. The machine itself—an SDS 940 mainframe—was thirty miles away in Menlo Park. He was controlling it remotely.

His team had leased two video lines from the telephone company, a massive expense and logistical nightmare. They had set up microwave transmitters on the roof of the civic center and on a truck parked on a ridge line to relay the signal.

In 1968, sending a video signal and a data signal simultaneously over thirty miles to a live audience was the equivalent of a moon landing.

The computer industry was built on a specific, rigid logic.

Computing Logic: Computers are scarce, expensive resources. Human time is cheap; computer time is expensive. Therefore, humans must prepare work offline (punch cards) to maximize the machine’s efficiency. Interactive computing wastes the machine’s time.

This logic governed the industry. It was why IBM was a titan. It was why office workers sat in rows with typewriters. It was the “correct“ way to do things.

It worked perfectly—until it met Douglas Engelbart.

Engelbart believed that human time was the precious resource, not the machine’s. He believed the machine should serve the mind, even if it was “inefficient” for the hardware.

As the lights went down in Brooks Hall, the hum of the crowd faded.

Engelbart looked small on the big stage. The screen behind him, a massive projection of his small monitor, glowed into life.

He spoke into his microphone, his voice steady but quiet.

“If in your office, you as an intellectual worker were supplied with a computer display, backed up by a computer that was alive for you all day, and was instantly responsive to every action you had, how much value could you derive from that?”

It was a question nobody had ever asked.

He moved his right hand.

On the massive screen, a small dot moved.

The audience froze.

He wasn’t typing coordinates. He wasn’t entering a command code. He was simply moving his hand, and the digital ghost on the screen followed him. He was using the wooden box with the wheels—the device his team had nicknamed “the mouse” because the cord looked like a tail.

Today, a cursor moving on a screen is as natural as breathing. In 1968, it was magic.

But he didn’t stop there.

He clicked on a word. It was highlighted.

He deleted it. It vanished.

The text around it snapped shut to fill the gap.

A murmur ran through the hall. He wasn’t rewriting the page. He

was manipulating information as if it were a physical object, yet it was made of light.

He showed them a “grocery list.” He categorized items. He collapsed the list so only the headers showed, then expanded it again to show the details.

He called this “view control.” We call it windowing.

He showed them a map. He clicked a link, and the screen jumped to a detailed diagram of a component. He clicked back, and he was at the map again.

He called it “hypermedia.” We call it the internet.

The demonstration continued, each minute adding a new impossibility to the list.

The tension in the control room was suffocating. Every second the system stayed online was a victory against the laws of probability. A single blown fuse, a misaligned microwave dish, a software bug—any of it would have turned the screen black and ended the dream.

Then came the moment that truly broke the room.

Engelbart introduced a colleague, Bill Paxton.

Paxton wasn’t on stage. He was thirty miles away, sitting in the lab at SRI.

His face appeared in a window on the screen, crisp and clear.

The audience gasped.

They were looking at a man in Menlo Park, while listening to a man in San Francisco, both looking at the same document on the same screen.

“Okay, Bill,” Engelbart said. “Let’s work on this together.”

On the screen, two cursors appeared. One controlled by Engelbart, one by Paxton.

They edited the text together. Engelbart would point to a sentence, and Paxton would paste it into a new location. They were collaborating, in real-time, across a distance, using a shared digital workspace.

It was Google Docs, Zoom, and Slack, demonstrated a year before the internet (ARPANET) even existed.

The audience, composed of the smartest engineers in the world, sat in stunned silence. They were watching science fiction become a documentary.

They weren’t just seeing new gadgets. They were seeing the destruction of their entire worldview. The idea of the solitary computer operator was dead. The idea of the computer as a mere calculator was dead.

Engelbart was showing them a window into a world where minds could connect through machines.

He typed, he clicked, he spoke. He operated a “chorded keyset” with his left hand, entering commands as fast as a pianist, while his right hand flew across the desk with the mouse. He was a conductor of information.

For ninety minutes, the system held.

The microwave links stayed true. The software didn’t crash. The mainframe thirty miles away processed every command.

When Engelbart finally took off the headset and the screen went dark, there was a pause.

A hesitation.

Then, the audience stood.

It wasn’t a polite golf clap. It was a roar. It was the sound of a thousand experts realizing that everything they knew about their field had just become obsolete.

They rushed the stage. They wanted to touch the mouse. They wanted to see the keyset. They wanted to know how he did it.

The “Mother of All Demos,” as it was later christened, did not immediately change the market. Engelbart did not become a billionaire. He was a researcher, not a salesman. His system was too expensive and too complex for the 1970s.

But the seeds were planted.

Sitting in the audience were the young engineers who would go on to work at Xerox PARC. They would take the mouse, the windows, and the graphical interface, and they would refine them.

Steve Jobs would visit Xerox PARC a decade later, see the descendants of Engelbart’s mouse, and use them to build the Macintosh.

Bill Gates would see it and build Windows.

Tim Berners-Lee would use the concept of hypermedia to build the World Wide Web.

Every smartphone in a pocket, every laptop in a cafe, every video call made to a loved one across the ocean—it all traces back to that ninety-minute window in 1968.

Douglas Engelbart died in 2013. He never sought fame. He watched as the world caught up to the vision he had seen clearly half a century before.

He proved that the pressure of the status quo—the belief that “this is how it’s always been done”—is brittle. It can be broken by a single person with a wooden box and the courage to show us what is possible.

The system said computers were for numbers.

He showed us they were for people.

Sources: Detailed in “The Mother of All Demos” archives (SRI International). Smithsonian Magazine, “The 1968 Demo That Changed Computing.” New York Times obituary for Douglas Engelbart, 2013. Summary of events from the Doug Engelbart Institute records.