“Property may be destroyed and money may lose its purchasing power; but, character, health, knowledge and good judgment will always be in demand under all conditions.”

Roger Babson – Educator (1875 – 1967)

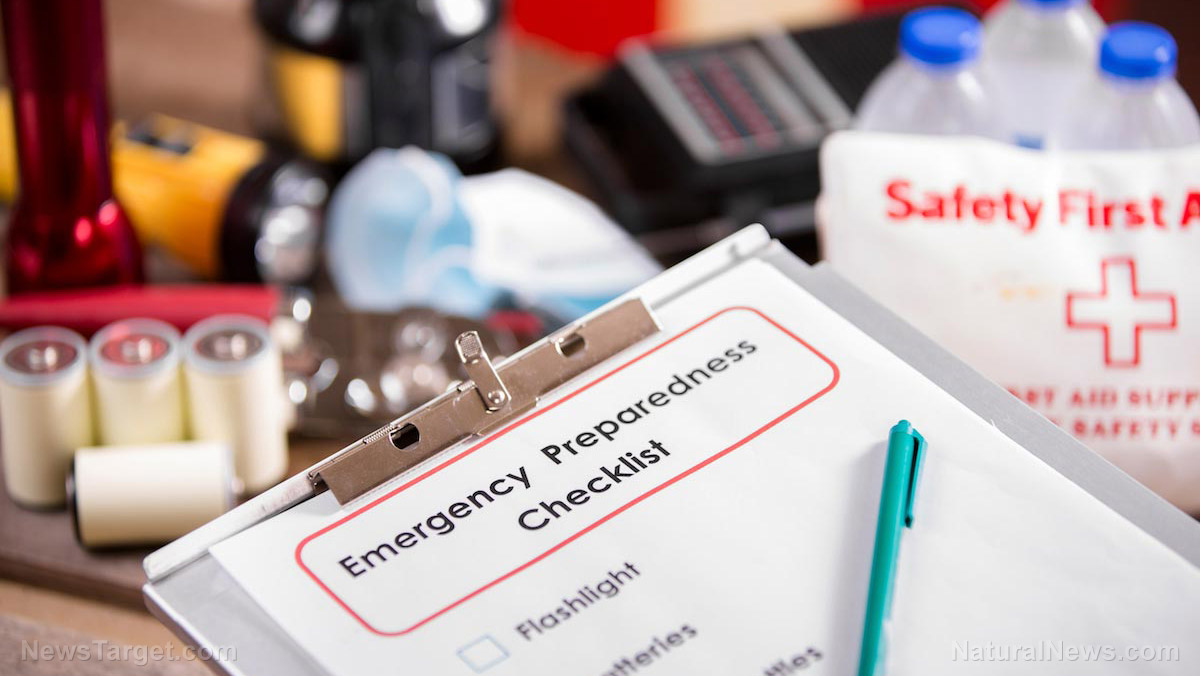

It’s not if, it’s when: why experts say every family needs a 72-hour disaster survival plan

- Prepare before disaster strikes with essential supplies and a clear plan.

- Build a 72-hour disaster kit with water, food, and critical safety items.

- Create and practice a family communication and evacuation plan regularly.

- Include your vehicle in preparedness with a kit, and keep the fuel tank full.

- Maintain readiness through ongoing reviews, drills, and safe generator use.

When disaster strikes your community, will your family be ready? Emergency managers across the nation are sounding the alarm that preparedness is no longer optional but a fundamental responsibility for every household.

“It’s not a question of if; it’s a question of when,” says Dale White, an emergency preparedness manager. The time to prepare is now, before the earthquake trembles, the floodwaters rise, or the wildfire smoke darkens the sky.

The cornerstone of readiness is a disaster supplies kit that enables your family to be self-sufficient for at least 72 hours. Authorities emphasize that help may not arrive immediately, and you might need to shelter in place. White suggests building your kit gradually. “Start by picking up an extra nonperishable food item or a water bottle on your weekly grocery trip,” he advises. “Before you know it, you’re going to have a decent amount of food and water.”

Your kit must include one gallon of water per person per day for at least three days, with clear plastic bottles recommended for longer shelf life. Add a three-day supply of nonperishable food and a manual can opener. Essential items include a first aid kit, prescription medications, a battery-powered or hand-crank radio, flashlights, and extra batteries. Do not forget a wrench to turn off utilities, plastic sheeting, a whistle, emergency blankets, a change of clothing with sturdy shoes, personal care items, copies of important documents, and cash.

Creating your family plan

A well-practiced plan is what transforms a collection of supplies into a lifeline. “Preparing your family makes everybody a lot calmer,” White notes. Your plan must identify two meeting places: one right outside your home for emergencies like fire, and another outside your neighborhood in case you cannot return home.

Every family should designate an out-of-town contact person. After a disaster, family members can call this relative or friend to relay information, as long-distance calls often go through when local lines are overwhelmed. Complete a family communication plan with all contact information and ensure every member carries a copy.

Practice is non-negotiable. Hold earthquake drills and practice “Drop, Cover, Hold.” Conduct fire drills, ensuring everyone knows two exits from each room. Critically, all adults should know how to shut off your home’s electricity, gas, and water, with the necessary tools kept nearby. Authorities caution that if you turn off gas, only a qualified professional can turn it back on, which could take weeks.

Don’t forget your vehicle

Your car is a key part of your strategy. “Chances are if you’re not at home, your car is going to be nearby,” White observes, or you may need to evacuate quickly. Keep your vehicle’s fuel tank above half full, as stations may be closed during emergencies. Maintain a smaller version of your disaster kit in the car, alongside a safety kit with jumper cables, flares, basic tools, and a paper map.

Special considerations are vital. If you have pets, include food, water, and carriers in your kit. For those with medical conditions or disabilities, plan for necessary equipment and medications. Remember, most public shelters do not accept pets for health reasons, so identify pet-friendly hotels or boarding facilities in advance.

The environmental aftermath of a disaster presents hidden dangers. Floodwater may contain raw sewage or hazardous chemicals. After flooding, mold growth becomes a serious health threat within 24 to 48 hours on wet materials. Standing water also becomes a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Proper cleanup is essential.

Perhaps the most dangerous post-disaster mistake is improper generator use. Officials alert that generator exhaust is toxic. “Always put generators outside well away from doors, windows, and vents,” warns the EPA. “Never use a generator inside homes, garages, crawl spaces, sheds, or similar areas.” Carbon monoxide poisoning is a silent, deadly killer.

True preparedness is not a single action but a maintained lifestyle. Review your plan every six months. Check and rotate your food and water supplies. Test smoke alarms monthly and replace batteries yearly. Conduct family drills. This ongoing commitment transforms fear into confidence.

In our modern world, we have sealed ourselves in tightly constructed homes, often disconnected from the natural rhythms that once guided human resilience. Preparing for disaster reconnects us with a fundamental truth: self-reliance is the first and most important response. Taking these steps today ensures that when the unexpected arrives, your family will not be victims waiting for help, but a capable team ready to respond.

MIT Courses Online

Lainey Wilson

American Idol rejected her 7 times. Never made it past the first round. She showered with a water hose in a flooded camper for three years. Ten years later, she became the first woman since Taylor Swift to win CMA Entertainer of the Year.

A farm girl from a 250-person town became country music’s biggest star by being “too country for country.”

Lainey Wilson was 19 years old.

Standing in line at an American Idol audition, waiting for hours with thousands of other hopefuls, convinced this was her moment.

It wasn’t.

She didn’t make it past the first round.

So she tried again. And again. And again. Seven times total. Seven rejections. Never once got to sing for the celebrity judges.

The Voice rejected her too.

Nobody wanted her.

Everyone in Nashville said the same thing.

“Too country for country.”

“Your twang is too thick.”

“Your sound doesn’t fit the market.”

“Go back to Louisiana.”

She didn’t listen.

Here’s what Lainey knew that everyone else missed… pop-infused country dominated the radio. But real country music wasn’t dead. The audience was still out there. Someone just had to give them something authentic.

So she bought a 20-foot Flagstaff camper trailer for $2,000. Hooked it up to her truck. Drove from Baskin, Louisiana to Nashville, Tennessee.

Population of her hometown: 250 people. Her father was a farmer. Her mother was a schoolteacher. She’d been writing songs since she was 9 years old.

She parked that camper in a recording studio parking lot. A man named Jerry Cupit owned the studio. He’d known her grandfather. Let her borrow electricity, water, and Wi-Fi to get by.

That camper became her home for the next three years.

The winters were brutal.

She slept in three or four jackets. Three pairs of socks. Still froze at night when the furnace couldn’t keep up.

Then her propane tank ran out. Then her shower head broke. Then the floor started rotting because the whole thing flooded.

She had to shower with a water hose.

Cold water. Ankle-deep in standing water. In a parking lot. In Nashville. For years.

“This is some shit,” she remembers thinking. “But whatever.”

She walked up and down Music Row. Handed out CDs and demos to anyone who would take one. Got the same response over and over.

Door after door. Rejection after rejection.

No publishing deal. No record deal. No interest.

For seven years.

She took every gig she could find. Performed Hannah Montana at kids’ parties during the day. Played her own songs at open mics at night.

People called her “the camper trailer girl.” Not as a compliment.

But she wasn’t there to be comfortable. She was there to be heard.

In 2014, everything collapsed at once.

Her mentor Jerry Cupit died. He was from Baskin, like her. Produced her first recordings. Believed in her when nobody else did. Let her park in his studio lot.

Gone.

Then she found out her boyfriend had been cheating. Got another woman pregnant.

“I learned to embrace the heartbreak,” she said.

She wrote hundreds of songs. Three hundred at least. Poured every broken piece into notebooks and recording sessions.

She released an album in 2014. Then another in 2016. Neither broke through. The industry kept telling her she wasn’t pop enough for modern country.

She signed a publishing deal in 2018. Then a record deal with BBR Music Group.

Still nothing happened. Not the way she’d dreamed.

Then Taylor Sheridan heard her music.

The creator of Yellowstone, the most-watched show on cable television, wanted her songs for the series.

In 2019, her music started appearing in episodes. Millions of people heard Lainey Wilson for the first time.

Sheridan called her in 2022. Said he wanted to create a role specifically for her.

“I want you on the show.”

She was terrified. She’d never acted before.

“I love doing things that are scary,” she said. “I love stepping outside my comfort zone.”

She became Abby on Yellowstone. A country singer. Not far from the truth.

But right when everything was finally working, her father got sick.

July 2022. Brian Wilson was hospitalized with a fungal infection that nearly killed him. Nine surgeries in a month. Lost his left eye. Parts of his face had to be removed. Had a stroke on top of it all.

She wanted to quit the show. Go home. Take care of him.

Her dad said no. Told her to keep going. To finish what she started.

So she did.

By September 2021, ten years and one day after she arrived in Nashville, her single “Things a Man Oughta Know” hit number one on the Country Airplay chart.

Ten years and one day. Exactly like they said.

But Lainey wasn’t done.

“Heart Like a Truck” went to number two. Then “Watermelon Moonshine.” Then “Wait in the Truck” with HARDY went double platinum.

In November 2023, she was nominated for five CMA Awards.

She won five. Including the big one.

Entertainer of the Year.

The first woman to win it since Taylor Swift in 2011.

“This is all I’ve ever wanted to do,” she said through tears at the podium. “It’s the only thing I know how to do. It finally feels like country music is starting to love me back.”

In February 2024, she won her first Grammy. Best Country Album for Bell Bottom Country.

In June 2024, she was inducted into the Grand Ole Opry. Her favorite moment so far.

In May 2024, she opened Bell Bottoms Up. A three-story bar, Cajun restaurant, and music venue in downtown Nashville. Right where Florida Georgia Line’s old bar used to be.

In November 2025, she won three more CMA Awards. Entertainer of the Year again. Album of the Year for Whirlwind. Female Vocalist of the Year for the fourth time.

Today, Lainey Wilson has 9 CMA Awards, 16 ACM Awards, a Grammy, and a role on the highest-rated show on cable television.

She’s engaged to former NFL quarterback Duck Hodges.

She played 102 shows in 2024. More stages than the number of people in her hometown.

All because a 19-year-old farm girl from a 250-person Louisiana town refused to stop auditioning after seven American Idol rejections.

She turned a flooded camper trailer into fuel for her fire.

She turned “too country for country” into the most authentic voice in Nashville.

She proved that the people who rejected you don’t get to write the end of your story.

What dream are you abandoning because you’ve been rejected seven times?

What version of “too different” are you letting define you instead of drive you?

What are you giving up on in year three when the breakthrough was waiting in year ten?

Lainey Wilson got told no by American Idol seven times. Never made it past the first round.

She lived in a camper with a rotting floor for three years. Slept in four jackets. Showered with a water hose.

Everyone in Nashville said she didn’t fit the market. Too twangy. Too traditional. Too country.

She walked Music Row handing out CDs for a decade. Got rejected at every door.

Then she hit number one. Won the Grammy. Won Entertainer of the Year twice.

Because she understood something most people don’t.

Ten years of rejection isn’t a sign you’re in the wrong game. It’s proof you’re willing to outlast everyone who quit in year three.

Your “too different” isn’t the reason you’re failing. It’s the reason you’ll eventually be the only option.

The people who rejected you don’t get to decide if you were right. The ones who find you ten years later do.

Stop waiting for permission from people who’ve already said no.

Start thinking like Lainey Wilson.

Show up when it’s uncomfortable. Keep going when it’s unfair. Outlast the timeline you thought you had.

And never let anyone convince you that the thing that makes you different is the thing that disqualifies you.

Sometimes the longest journeys produce the biggest breakthroughs.

Because when everyone else quits in year three, the person still standing in year ten doesn’t have any competition left.

Don’t quit.

Quote of the Day

“If you realized how powerful your thoughts are, you would never think a negative thought.”

Peace Pilgrim – Activist (1908 – 1981)

The Highest Level of Statesmanship

With all that is going on it pays to remind ourselves of the words of Lord Acton:

“The idea that the object of constitutions is not to confirm the predominance of any interest, but to prevent it; to preserve with equal care the independence of labour and the security of property; to make the rich safe against envy, and the poor against oppression, marks the highest level attained by the statesmanship of Greece.” – Lord Acton

Quote of the Day

“Happiness is an inside job.”

William Arthur Ward – Writer (1921 – 1994)

Carol Kaye

Some people change the world so quietly that the world doesn’t notice until decades later.

Los Angeles, 1963. A bass player didn’t show up for a recording session. The studio needed someone immediately. They looked around the room.

“Carol, can you play bass?”

Carol Kaye had never really touched a bass guitar before. But she didn’t say no to challenges. She picked up the instrument, figured out the part, and played the session.

That moment—born from someone else’s absence, from pure chance—changed the sound of popular music forever.

Carol Kaye became one of the most recorded bass guitarists in history. She played on an estimated 10,000 recordings. She created bass lines that became part of your DNA even if you never knew who played them.

And for decades, almost nobody outside the music industry knew her name.

But the musicians knew. When you needed a bass line that was clean, creative, and absolutely perfect, you called Carol Kaye.

Born in 1935 in Everett, Washington, Carol grew up during the Depression in a family that struggled. Music became her escape and eventually her survival.

She taught herself guitar as a teenager, learning bebop jazz by listening to records and figuring out the changes by ear. By her early twenties, she was skilled enough to play clubs alongside jazz legends in Los Angeles.

Throughout the 1950s, Carol worked the LA jazz scene. Bebop clubs on Central Avenue. Backing touring musicians. Making a living doing what she loved.

She was professional, talented, and respected in a world that didn’t often respect women musicians.

Then came the early 1960s and The Wrecking Crew. The loose collective of Los Angeles session musicians who played on countless hit records.

These weren’t the artists whose faces appeared on album covers. They were the anonymous professionals who actually played the instruments while the “bands” often just sang.

And Carol Kaye became one of their most indispensable members. And the only regular female member of the crew.

After that first bass session in 1963, Carol realized something. She was good at this. Really good.

The bass let her be melodic and rhythmic simultaneously. It let her create foundations that were simple enough to support a song but interesting enough to make it unforgettable.

Producers started requesting her specifically. Word spread. Carol Kaye could play anything. She was fast. Creative. Professional.

And she brought something special. A melodic sensibility from her jazz background combined with the pocket and precision that pop music demanded.

In 1966, Brian Wilson created Pet Sounds, the Beach Boys album that would redefine pop music. Carol played bass on “Good Vibrations.”

Her lines weren’t just accompaniment. They were architectural. They gave the songs movement, color, emotional depth.

She played on Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” productions. She played on Motown hits when Detroit labels brought their artists to LA. The Supremes. The Temptations.

Those iconic bass lines that made you want to dance? Many were Carol.

She played on Monkees hits. Barbra Streisand recordings. Frank Sinatra’s. The Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’”—one of the most-played songs in radio history.

That’s Carol on bass.

And the MASH theme—“Suicide Is Painless.” That iconic, melancholy bass line? Carol Kaye.

She wasn’t just playing notes written on a chart. She was often creating the parts herself. Writing bass lines on the spot that became essential to the songs’ identities.

She was a composer without credit. An architect without recognition.

And here’s what makes Carol’s story both remarkable and infuriating. She was rarely credited.

Session musicians in that era typically weren’t. No royalties. No album credits. No acknowledgment.

For a woman in that environment, it was even harder. Carol had to be twice as good to get the same respect. She had to prove herself constantly in a world that assumed men were better musicians simply by virtue of being men.

She had to be perfect every time.

And she was.

Paul McCartney has called her one of the great bass players. Geddy Lee of Rush has praised her technique. Sting has acknowledged her influence.

These bass legends—men who became famous for their instrument—recognize Carol as a pioneer and master.

In 1976, Carol’s life changed suddenly. A car accident severely injured her hands and arms.

For a bassist, this is catastrophic. Her career as a session player effectively ended.

She could have disappeared. Many musicians do.

Carol chose differently.

After surgery and extensive recovery, she returned to music as a teacher. She began sharing everything she’d learned in those thousands of sessions.

She wrote instruction books. She mentored young musicians. She insisted, gently but firmly, that her contributions be acknowledged.

And slowly, the world started listening.

Today, at ninety years old, Carol Kaye is still teaching. Still inspiring new generations of bassists who are just discovering that the sounds they’ve been listening to their entire lives were shaped by this remarkable woman.

She doesn’t do it for fame. She never did.

She does it because music is what she loves, what she knows, what she has to give.

Carol Kaye’s story teaches us something crucial about greatness. It doesn’t always announce itself.

Sometimes, real greatness shows up, does extraordinary work, and moves on to the next job without needing applause.

But history remembers.

Carol Kaye was one of the architects of modern popular music. She created sounds that became part of global culture.

She proved that women belonged in recording studios not as novelties but as equals. As masters of their craft who could outplay almost anyone.

The next time you hear “Good Vibrations,” or the MASH theme, or any of dozens of classic songs from the 1960s and 70s, listen for the bass.

Really listen.

That’s Carol Kaye. That’s the sound of greatness that didn’t need to shout—because it knew how to create the rhythm that makes songs last forever.

She didn’t demand her place in history.

She earned it. One bass line at a time.

For decades, the world danced to her rhythms without knowing her name. Radio stations played her work thousands of times a day. Musicians built careers on songs she’d helped create.

And she just kept working. Session after session. Song after song. Creating the invisible architecture that held popular music together.

No ego. No demands for recognition. Just excellence repeated ten thousand times.

That’s a different kind of power. The kind that doesn’t need credit to matter. The kind that shapes culture from the inside out.

Carol Kaye changed what bass guitar could be. She brought jazz sophistication to pop simplicity. She made the instrument melodic when everyone else treated it as just rhythm.

She did it while being the only woman in rooms full of men who didn’t always want her there. She did it while raising children. She did it while fighting for fair pay and basic respect.

And she did it so well that her work became timeless.

Ninety years old and still teaching. Still sharing. Still making sure the next generation understands that greatness doesn’t require fame.

It just requires showing up, doing the work, and doing it better than almost anyone else can.

For those who’ve ever done excellent work that nobody noticed—what kept you going when the recognition never came but you knew the work mattered anyway?

Colonel David Hackworth

Colonel David Hackworth went on national television in 1971 and accused the U.S. Army of failing its own soldiers during the Vietnam War, knowing the interview would likely end his career.

At the time, David Hackworth was one of the most decorated officers in the military. He had earned eight Purple Hearts, two Distinguished Service Crosses, and more than 90 medals across Korea and Vietnam. Inside the Army, he was considered a combat legend. On May 27, 1971, sitting under studio lights on ABC’s Issues and Answers, he became something else.

A whistleblower in uniform.

Hackworth did not speak in generalities. He described drug use spreading through combat units, officers chasing body count statistics instead of protecting troops, and leadership decisions that he said were getting soldiers killed. He called the situation “a crisis in leadership” and warned that the Army was breaking down from the inside.

The reaction was immediate.

Pentagon officials were furious. Senior commanders accused him of disloyalty and exaggeration. Investigations into his conduct began within weeks. Hackworth later said he understood the risk before he spoke. “I knew when I did that interview, my career was over.”

The scrutiny intensified.

Military auditors examined his finances, his awards, and his command decisions. Hackworth denied wrongdoing, but the pressure mounted. Facing potential court martial and the collapse of his position, he resigned from the Army in 1971 after 26 years of service.

The consequences followed him into civilian life.

Some veterans saw him as a truth teller who spoke for enlisted soldiers. Others viewed him as a traitor who publicly attacked the military during wartime. The division never fully disappeared.

But Hackworth did not retreat.

In 1989, he published About Face, a 700 page memoir that detailed corruption, poor leadership, and systemic failures inside the Army. The book became a bestseller and is still used in military leadership courses. Later, as a military analyst for Newsweek and television networks, he continued criticizing Pentagon decisions, including readiness problems in the 1990s.

The irony defined his career.

David Hackworth had built his reputation by fighting wars aggressively and leading from the front. In Vietnam, he had created “Tiger Force” style units designed for mobility and survival, pushing commanders to reduce casualties rather than chase statistics.

His most controversial battle was not against an enemy.

It was against his own institution.

Colonel David Hackworth did not destroy his career because he opposed the military.

He risked it because he believed loyalty to soldiers mattered more than loyalty to the system that was failing them.

The Hawthorne Effect

1. In 1924, researcher Elton Mayo conducted an experiment that many later tried to bury. He told workers they were being “observed for productivity.” And it was true — they were constantly monitored. Yet within weeks, they began to improve: more focus, higher output, greater initiative. A simple observation changed real behavior — as if the brain had received a “silent command.”

2. Years later, other researchers repeated the study with self-observation. One group was told they possessed an “internal monitoring ability.” The tasks were identical, but those who observed their own thoughts produced responses that were 94% more accurate. The scientists were clear: “We didn’t increase ability. We changed the way they observed themselves.”

3. One participant summarized it this way: “I just watched my thoughts… and then I controlled them.” Mayo explained that when the mind directs conscious attention toward itself, the body begins to act as if under direct command. The brain doesn’t respond to talent — it responds to self-observation.

4. The dark side is the opposite: when someone ignores their own thoughts and lives on autopilot, the brain acts chaotically. Lack of self-observation reduces mental control almost as much as chronic fatigue. The body operates without direction, aligning with the internal void that’s been created.

5. A Harvard psychologist put it plainly: “We become aware of who we are when we watch our thoughts — until we realize we never did.” By changing internal self-observation, the nervous system reorganizes. This is the moment you stop living on autopilot and start living consciously.