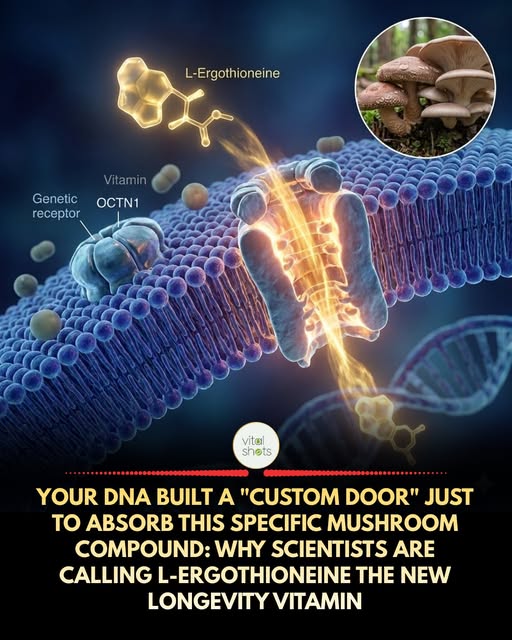

In evolutionary biology, the human body does not waste energy building things it doesn’t absolutely need.

If your DNA codes for a specific receptor, it means that whatever fits into that receptor is critical for your survival.

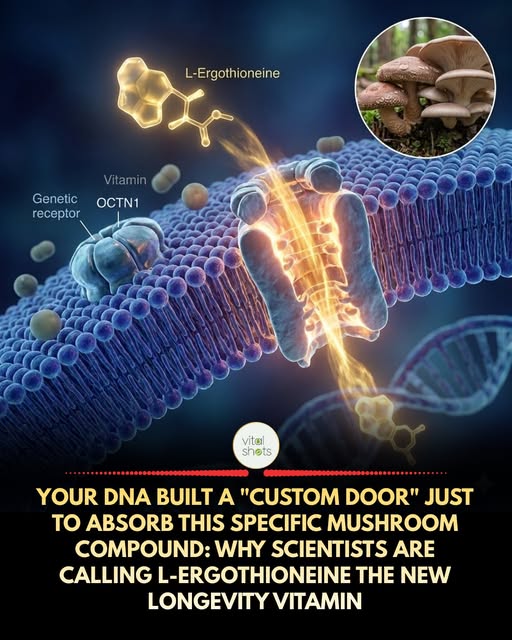

In 2005, scientists made a stunning discovery. They found a specific transport protein in human cells called OCTN1.

They tested hundreds of nutrients to see what this transporter was designed to carry. It ignored almost everything.

It only opened its doors for one rare molecule: L-Ergothioneine (ERGO).

What is L-Ergothioneine?

ERGO is a powerful, rare amino acid that acts as a master antioxidant. But here is the catch: Humans cannot synthesize it. Plants cannot synthesize it. Animals cannot synthesize it.

It is created almost entirely by Fungi (Mushrooms) and certain soil bacteria.

The fact that human genetics evolved a highly specific, customized transportation system just to pull this fungal compound into our red blood cells and central nervous system proves that our ancestors ate massive amounts of mushrooms. Our biology literally expects it.

The “Longevity Vitamin”

Dr. Bruce Ames, an incredibly renowned biochemist at UC Berkeley, proposed classifying ERGO as a “Longevity Vitamin.”

Unlike standard antioxidants (like Vitamin C) which float around the blood and degrade quickly, ERGO is actively pumped inside the cells and stays there for over a month.

It specifically targets the mitochondria and the DNA, acting as an indestructible shield against oxidative stress.

The Clinical Data: Studies comparing blood levels of ERGO across populations show a striking correlation. In regions where mushroom consumption is high (like Japan and Italy), ERGO levels are high, and the rates of neurodegenerative diseases (like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s) are significantly lower than in the US, where mushroom consumption is minimal.

The Soil Depletion Crisis

We used to get ERGO indirectly. Cows would eat grass grown in healthy, fungi-rich soil, and we would get the ERGO from the meat or milk.

But modern industrial agriculture (tilling, fungicides, and synthetic fertilizers) has decimated the mycorrhizal fungi networks in the soil. The ERGO is gone from our food chain.

How to get your ERGO:

To fulfill this genetic requirement, you must actively add fungi back into your diet.

The Best Sources: White button mushrooms have very little. You need to eat Oyster Mushrooms, Shiitake, King Oyster, and Porcini.

The Cooking Rule: Unlike many vitamins, ERGO is incredibly heat stable. Cooking the mushrooms actually helps break down their tough chitin cell walls, making the ERGO more bioavailable.

Supplementation: If you hate eating mushrooms, isolated L-Ergothioneine supplements (often derived from fermented yeast) are now hitting the longevity market. Taking 5mg to 10mg daily saturates your OCTN1 receptors, providing your brain with the fungal shield it was genetically designed to have.

Source: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), “Prolonging healthy aging: Longevity vitamins and proteins“, Dr. Bruce Ames.

In evolutionary biology, the human body does not waste energy building things it doesn’t absolutely need.

If your DNA codes for a specific receptor, it means that whatever fits into that receptor is critical for your survival.

In 2005, scientists made a stunning discovery. They found a specific transport protein in human cells called OCTN1.

They tested hundreds of nutrients to see what this transporter was designed to carry. It ignored almost everything.

It only opened its doors for one rare molecule: L-Ergothioneine (ERGO).

What is L-Ergothioneine?

ERGO is a powerful, rare amino acid that acts as a master antioxidant. But here is the catch: Humans cannot synthesize it. Plants cannot synthesize it. Animals cannot synthesize it.

It is created almost entirely by Fungi (Mushrooms) and certain soil bacteria.

The fact that human genetics evolved a highly specific, customized transportation system just to pull this fungal compound into our red blood cells and central nervous system proves that our ancestors ate massive amounts of mushrooms. Our biology literally expects it.

The “Longevity Vitamin”

Dr. Bruce Ames, an incredibly renowned biochemist at UC Berkeley, proposed classifying ERGO as a “Longevity Vitamin.”

Unlike standard antioxidants (like Vitamin C) which float around the blood and degrade quickly, ERGO is actively pumped inside the cells and stays there for over a month.

It specifically targets the mitochondria and the DNA, acting as an indestructible shield against oxidative stress.

The Clinical Data: Studies comparing blood levels of ERGO across populations show a striking correlation. In regions where mushroom consumption is high (like Japan and Italy), ERGO levels are high, and the rates of neurodegenerative diseases (like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s) are significantly lower than in the US, where mushroom consumption is minimal.

The Soil Depletion Crisis

We used to get ERGO indirectly. Cows would eat grass grown in healthy, fungi-rich soil, and we would get the ERGO from the meat or milk.

But modern industrial agriculture (tilling, fungicides, and synthetic fertilizers) has decimated the mycorrhizal fungi networks in the soil. The ERGO is gone from our food chain.

How to get your ERGO:

To fulfill this genetic requirement, you must actively add fungi back into your diet.

The Best Sources: White button mushrooms have very little. You need to eat Oyster Mushrooms, Shiitake, King Oyster, and Porcini.

The Cooking Rule: Unlike many vitamins, ERGO is incredibly heat stable. Cooking the mushrooms actually helps break down their tough chitin cell walls, making the ERGO more bioavailable.

Supplementation: If you hate eating mushrooms, isolated L-Ergothioneine supplements (often derived from fermented yeast) are now hitting the longevity market. Taking 5mg to 10mg daily saturates your OCTN1 receptors, providing your brain with the fungal shield it was genetically designed to have.

Source: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), “Prolonging healthy aging: Longevity vitamins and proteins“, Dr. Bruce Ames.