The gray dust of Macon County, Alabama, did not smell like earth. It smelled like ash. In October of 1896, a man in a crisp suit knelt in a field that had refused to grow a crop for three years. He ran the dry powder through long, sensitive fingers.

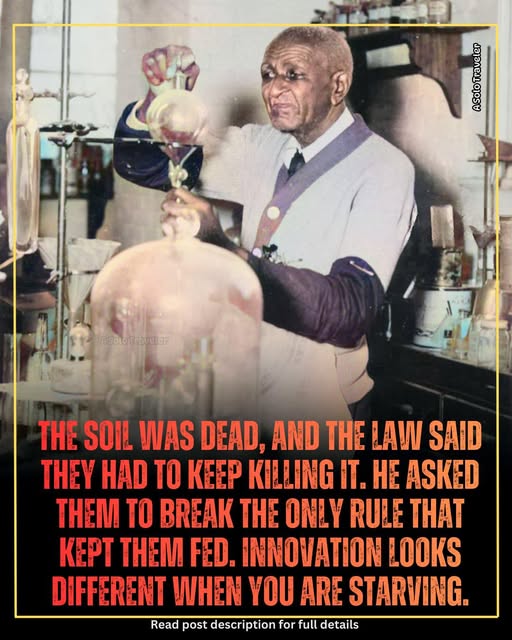

There was no life in it. The man was George Washington Carver, and he had just arrived from Iowa State University. He held a master’s degree in agricultural science, but standing there in the heat, he realized his degree meant nothing to this dead ground. The soil was not resting. It was starving.

He looked up at the farmhouse. It was a single-room shack with gaping holes in the walls. The family watching him was gaunt, their eyes hollow from a diet of salt pork and cornmeal. They were waiting for him to leave so they could go back to worrying about how to survive the winter. They did not know that the man kneeling in their dirt was about to start a war against the economy of the entire South.

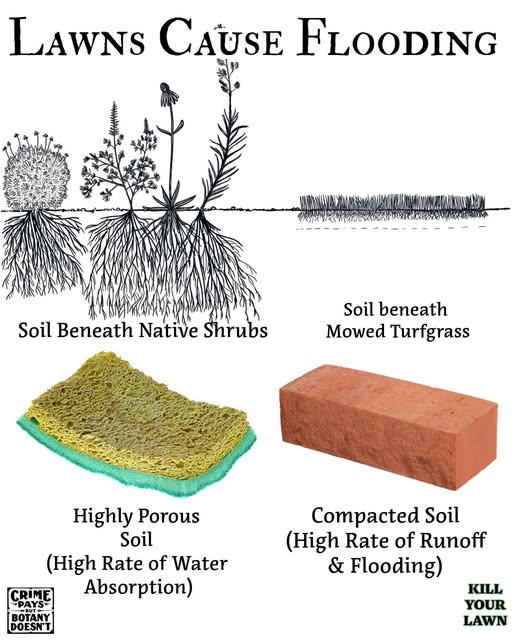

The problem was visible in every direction. For decades, the South had planted only one thing. Cotton was the currency, the culture, and the king. But cotton is a cruel master. It acts like a vampire to the soil, sucking out the nitrogen and nutrients until the earth turns to dust.

In the late 19th century, the cycle was brutal. Farmers, both Black and white, lived as sharecroppers. They did not own the land they worked. They borrowed tools, seeds, and food from the landowner or the local merchant, promising to pay it back with the harvest. It was a system designed to keep people in debt.

When the soil died, the harvest failed. When the harvest failed, the debt grew. Families were trapped in a prison without bars, bound to land that could no longer feed them. Carver saw this within his first month at the Tuskegee Institute. He saw children with bowed legs from rickets and swollen bellies from pellagra. He realized that before he could be a scientist, he had to be a survivalist.

He tried to explain the chemistry. He told them that the land needed to rest from cotton. He told them to plant cowpeas, sweet potatoes, or peanuts—crops that would pull nitrogen from the air and put it back into the ground.

The system did not allow it.

The Southern agricultural economy was a locked engine. Banks and merchants would not lend money for peanuts or peas. They only recognized cotton. The “crop lien” system meant that a farmer’s future harvest was already owned by the merchant before a single seed was planted. If a farmer tried to plant sweet potatoes to feed his starving children, the merchant cut off his credit. No credit meant no tools, no seed, and no food for the winter. The rule was absolute: Plant cotton, or starve immediately.

This economic machine worked perfectly for the few who owned the ledgers. It worked until it met a man who did not care about money, but cared deeply about nitrogen.

Carver stood on a porch in 1897, holding a handful of dried cowpeas. He offered them to a weathered farmer who had just lost his entire cotton crop to disease. The farmer looked at the peas, then at his barren field, and shook his head. He didn’t take them. He couldn’t. Taking the peas meant breaking the contract with the merchant. It was a quiet rejection, born of fear. Carver put the peas back in his pocket. He realized then that being right was not enough.

He retreated to his laboratory, but not to hide. He began to experiment not with high-yield fertilizers that the poor could not afford, but with swamp muck and forest leaves. He turned compost into gold. But he knew the farmers would not come to the school. They were too tired, too poor, and too ashamed of their clothes.

If the people could not go to the school, the school would have to go to the people.

Carver designed a wagon. It was known as the Jesup Agricultural Wagon, a “Movable School.” It was a strange sight—a sturdy carriage loaded with churns, jars, seeds, and plows, pulled by mules across the rough, red-clay roads.

The struggle was slow and exhausting. Carver would pull the wagon up to a church or a dusty crossroads. People would gather, skeptical. They expected a preacher or a tax collector. Instead, they got a man with a high voice who rolled up his sleeves and started digging in the dirt.

He did not lecture them on chemistry. He showed them. He would take a small patch of their ruined land and work it his way. He used the muck from the swamps to fertilize it. He planted the “forbidden” crops—the legumes and the sweet potatoes.

Week after week, month after month, he returned. The farmers watched. They saw the patch of land Carver tended turn dark and rich. They saw the cotton in his demonstration plot grow tall, while their own plants remained stunted.

But the fear of the merchants remained. To break it, Carver had to prove that the alternative crops had value. He wasn’t just fighting bad farming; he was fighting the market. If they couldn’t sell peanuts, they wouldn’t plant them.

So, he went into his laboratory at dawn and came out at dusk. He took the humble peanut and the sweet potato and dismantled them chemically. He found milk, oil, flour, dyes, and soaps hidden inside. He created recipes. He printed bulletins on cheap paper—simple guides on how to cook and preserve these new crops so that even if the merchants wouldn’t buy them, the families could eat them.

He handed out these bulletins from the back of his wagon. He cooked meals for the farmers’ wives, showing them that the “weed” called the peanut could replace the expensive meat they couldn’t afford.

Slowly, the grip of the system loosened. A farmer here, a family there, began to hide a patch of peanuts or sweet potatoes in the back acres. They saw their children grow stronger. They saw the soil in those patches turn dark again. When the boll weevil beetle eventually marched across the South, devouring the cotton fields and bankrupting the old system, the farmers who had listened to the man on the wagon did not starve. They had something else to sell. They had something else to eat.

Carver never patented his discoveries. He claimed the methods came from God and belonged to the people. By the time he was an old man, the South was green again. The gray dust was gone, buried under layers of rich, restored earth.

He had not just fixed the soil. He had broken the economic chains that bound the poor to a dying crop. He proved that science only matters when it serves the person with the least amount of power.

Sources: Tuskegee University Archives; McMurry, L. O. (1981), George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol.