In February 1956, Harry deLeyer arrived late to a horse auction in Pennsylvania.

The auction was over. The valuable horses were gone. The only animals left were the ones nobody wanted—skinny, used-up horses being loaded onto a truck bound for the slaughterhouse in Northport.

Harry was a 28-year-old Dutch immigrant who taught riding at a private school on Long Island. He needed quiet horses for his beginner students. Nothing fancy. Just something safe.

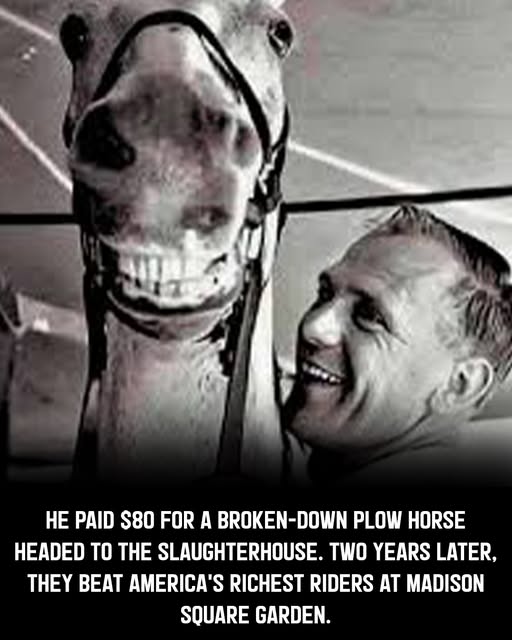

Then he saw him.

A gray gelding, eight years old, filthy and covered in scars from years pulling an Amish plow. The owner warned Harry against buying him. “He’s not sound. He has a hole in his shoulder from the plow harness.”

Harry looked at the horse anyway.

Wide body. Calm demeanor. Intelligent eyes. Good legs despite everything.

“How much?”

“Eighty dollars.”

Harry paid it. The horse stepped off the slaughter truck and into history.

His daughter named him Snowman.

For a few months, Snowman was exactly what Harry needed—a gentle lesson horse the children loved. So gentle, in fact, that Harry eventually sold him to a local doctor for double what he’d paid.

The doctor took Snowman home.

Snowman had other plans.

The next morning, Snowman was back in Harry’s barn.

The doctor took him home again. Built higher fences.

Snowman jumped them. Came back.

Five-foot fences. The horse who’d spent his life pulling a plow was clearing five-foot fences like they were nothing.

Harry stared at this $80 plow horse and saw something nobody else had seen.

Maybe this horse could jump.

In 1958—exactly two years after Harry pulled him off that slaughter truck—Snowman and Harry deLeyer walked into Madison Square Garden.

They were competing against America’s elite show jumpers. Horses with perfect bloodlines. Horses worth tens of thousands of dollars. Horses owned by millionaires who’d never looked at a plow, much less pulled one.

Snowman was still that wide, plain gray gelding.

Still had scars on his shoulder.

Still had the thick neck and powerful hindquarters of a working farm horse.

He won.

Not just won—dominated. The AHSA Horse of the Year. The Professional Horsemen’s Association championship. The National Horse Show championship. Show jumping’s triple crown.

The press went wild. LIFE Magazine called it “the greatest ‘nags-to-riches’ story since Black Beauty.”

They called Snowman “The Cinderella Horse.”

In 1959, they did it again.

Back to Madison Square Garden. Back against the blue-blood horses and their millionaire owners.

Snowman won again. Horse of the Year. Again.

The crowd couldn’t get enough of them. This immigrant riding instructor and his $80 rescue horse, beating horses that cost more than houses.

Snowman jumped obstacles up to seven feet, two inches high. He jumped over other horses. He jumped with a care and precision that made it look easy, even when it wasn’t.

And here’s the part that made people love him even more: the same horse who cleared seven-foot jumps on Saturday could lead a child around the ring on Sunday. Snowman could win an open jumper championship in the morning and a leadline class in the afternoon.

He was called “the people’s horse.”

Snowman and Harry traveled the world. They appeared on television shows. Johnny Carson. National broadcasts. Snowman became as famous as any human athlete.

Secretariat wouldn’t be born for another decade. But people compared Snowman to Seabiscuit—another long-shot champion who’d captured America’s heart in darker times.

The Cold War was raging. The country was anxious. And here was this story: an immigrant and a rescue horse, proving that being born into nothing didn’t mean you were worth nothing.

That the $80 horse could beat the $30,000 horses.

That where you came from mattered less than where you were willing to go.

Snowman competed until 1969.

His final performance was at Madison Square Garden, where it had all started. He was 21 years old—elderly for a show jumper. The crowd gave him a standing ovation. They sang “Auld Lang Syne.”

He retired to Harry’s farm in Virginia, where he lived peacefully for five more years.

Children still came to see him. To touch the horse who’d become a legend. To feed carrots to the champion who’d once been hours away from becoming dog food.

Snowman died on September 24, 1974.

He was 26 years old. Kidney failure.

Harry deLeyer kept teaching, kept training, kept competing. He never found another horse like Snowman. Nobody did.

In 1992—eighteen years after Snowman’s death—the horse was inducted into the Show Jumping Hall of Fame.

In 2011, author Elizabeth Letts wrote “The Eighty-Dollar Champion: Snowman, the Horse That Inspired a Nation.” It became a #1 New York Times bestseller.

In 2015, when Harry was 86 years old, a documentary premiered: “Harry & Snowman.” For the first time, Harry told the whole story himself. His childhood in Nazi-occupied Netherlands, where his family hid Jews in a secret cellar beneath the barn. His immigration to America with nothing. His late arrival at that Pennsylvania auction.

That gray horse on the slaughter truck.

Eighty dollars.

That’s what it cost to save Snowman’s life.

It’s also what it cost to prove that champions aren’t always born in fancy stables with perfect bloodlines.

Sometimes they’re born in Amish fields, pulling plows until their shoulders scar.

Sometimes they’re saved by immigrants who arrive late to auctions and see something nobody else saw.

Sometimes the longest long shot becomes the surest thing.

Harry deLeyer died on June 25, 2021, at age 93.

The obituaries called him many things: riding instructor, champion, immigrant, hero.

But the title he probably loved most was simple.

Snowman’s rider.

The man who paid $80 for a plow horse and got a friend, a champion, and a story that would last forever.