Doing the right thing is very rarely the wrong thing to do.

Weeks into recording “Hotel California” from the album “Hotel California” released in 1976, the Eagles faced a brutal realization. The master take sat in the wrong key for Don Henley’s vocal range. After investing countless studio hours polishing the arrangement, layering guitars, and tightening harmonies, the band made a costly decision. They scrapped the entire version and started again from the ground up.

The foundation of the track came from guitarist Don Felder, who had assembled a series of demo ideas on a 12 string guitar. When the band began shaping it in the studio, the instrumental track felt powerful and expansive. Henley pushed his voice to meet the melody line, but as sessions progressed, strain became obvious. The key demanded sustained high notes that could not hold up across multiple takes. Recording an album at that level of intensity meant repeating vocals for precision. A key that felt barely manageable on day one became punishing after weeks.

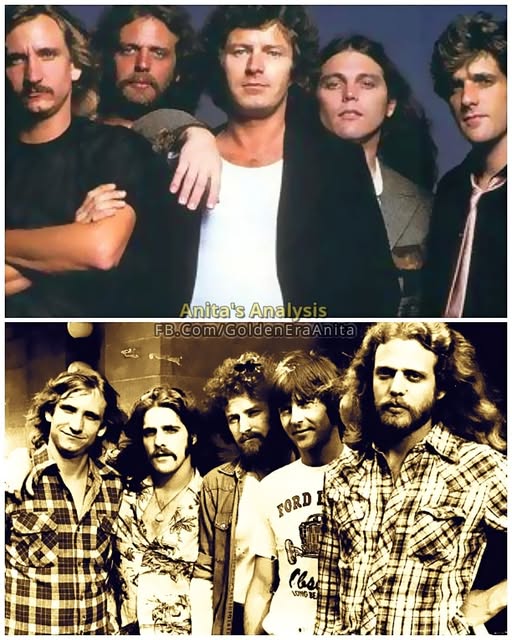

Producer Bill Szymczyk recognized the issue while listening to playback. Technically, nothing was wrong with the arrangement. The rhythm section locked in tightly. Joe Walsh and Don Felder were refining what would become one of the most recognizable dual guitar sequences in rock history. Randy Meisner had already departed the band by that time, leaving Timothy B. Schmit to handle bass duties during the later touring era, though the album sessions still reflected the earlier lineup transition period. The problem centered on sustainability. Henley’s voice carried emotional weight in “Desperado” from 1973 and “One of These Nights” from 1975, yet this melody required a slightly lower placement to preserve strength and tone.

Lowering the key meant dismantling everything. Guitar voicings changed. Chord shapes shifted. Harmonic textures had to be rebuilt. Tape in the mid 1970s was expensive, and studio time in Los Angeles did not come cheap. The band had already invested heavily in making “Hotel California” the defining statement of their career. Letting go of a completed version required discipline few artists demonstrate at that stage of success.

Henley later acknowledged in interviews that he preferred singing within a range that allowed intensity without damage. Touring schedules added pressure. A recording key that barely worked in the studio could collapse under the stress of nightly concerts. The Eagles had learned from earlier albums like “On the Border” released in 1974 that studio precision must translate to the stage. If the song became a single, which it eventually did in 1977, it needed to hold up in arenas.

The restart process sharpened the band’s focus. Instead of treating the setback as failure, they approached it as refinement. Joe Walsh, who had joined prior to the album’s release, contributed textural guitar work that deepened the atmosphere. Felder reworked his parts to match the adjusted pitch. Henley delivered vocals with greater control once the melody sat comfortably in his range. What had begun as a technical obstacle transformed into a defining strength.

There was also a psychological element. By 1976, the Eagles were no longer a developing act. They were expected to produce a landmark record. Pressure mounted from both the label and the industry. Starting over signaled that they valued longevity over convenience. Sacrificing weeks of labor showed a commitment to quality that shaped the final sound.

The finished recording of “Hotel California” achieved commercial and critical success, winning the Grammy Award for Record of the Year in 1978. Listeners never heard the discarded version. They heard a performance balanced between power and restraint. That balance existed because the band confronted a mistake early enough to correct it.

Choosing to reset the key preserved Henley’s vocal authority and secured the song’s durability for decades of live performances, proving that technical humility can define artistic permanence.