Some data on one of the many ingredients in my NutriBlast Greens Plus.

Tom's Blog on Life and Livingness

Some data on one of the many ingredients in my NutriBlast Greens Plus.

An experimental AI trading bot was given a crypto wallet and tried to send someone about $500 in digital coins – but due to what looks like a technical mistake, it accidentally sent its entire stash worth about $250,000. The recipient quickly sold the coins for around $40,000, though they’d be worth much more now. The bot is now getting people to do random tasks in exchange for $500 worth of that coin.

Finish reading: https://www.zerohedge.com/ai/rogue-ai-just-yeeted-250000-void?utm_source=daily_newsletter

“The strength or weakness of a society depends more on the level of its spiritual life than on its level of industrialization. Neither a market economy nor even general abundance constitutes the crowning achievement of human life. If a nation’s spiritual energies have been exhausted, it will not be saved from collapse by the most perfect government structure or by any industrial development. A tree with a rotten core cannot stand.” – Alexander Solzhenitzyn

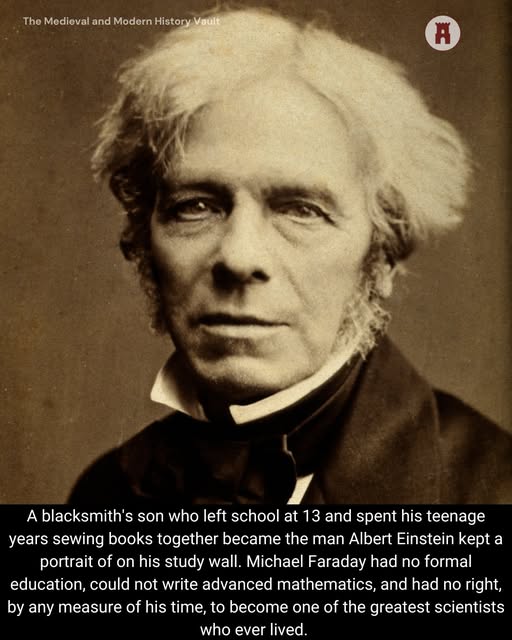

Michael Faraday was born in 1791 in Newington Butts, south London, the son of a blacksmith who was frequently too ill to work. The family was often hungry. His education consisted of learning to read, write, and do basic arithmetic at a church Sunday school, and that was where it ended. At the age of 13 he was running errands for a bookbinder and bookseller. At 14 he was apprenticed to the man, George Riebau of Blandford Street, Marylebone, for a seven-year term. Unlike every other apprentice in that shop, Faraday read every book that came in to be bound.

He read the entry on electricity in the third edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and was so captivated that he built himself a crude electrostatic generator out of old bottles and lumber. He read Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry and began conducting his own chemical experiments. He joined the City Philosophical Society in 1810, a group of young working men who met weekly to hear lectures on science and discuss what they had learned. He was educating himself in the only way available to him, from the inside of a trade he had no intention of staying in.

In 1812, a customer at the bookshop gave the 20-year-old Faraday four tickets to attend lectures at the Royal Institution by Sir Humphry Davy, then the most celebrated chemist in Britain. Faraday attended every one, taking meticulous notes in the careful hand of a man who had taught himself to write properly. He bound those notes into a beautiful 300-page volume and sent them to Davy with a letter asking for any position in science, however small. Davy wrote back kindly but said there was nothing available.

Then, a few months later, Davy’s laboratory assistant was dismissed after getting into a fight. Davy remembered the eager young bookbinder. In March 1813, Faraday was hired as a laboratory assistant at the Royal Institution at 25 shillings a week, two rooms in the attic, and the use of the laboratory. It was, in the judgment of history, one of the most consequential hiring decisions ever made.

Within a year, Davy took Faraday on an 18-month tour of Europe, where he met many of the leading scientists of the age. Back in London, Faraday began his own research. In 1821 he invented the electric motor, demonstrating that electrical current could produce continuous mechanical motion, a concept nobody had achieved before. By 1831 he had made the discovery that would change the world: electromagnetic induction. By passing a magnet through a coil of wire, he generated an electric current. This was the first electrical generator, the foundational principle behind every power station ever built.

He went on to discover the laws of electrolysis, coined the terms electrode, anode, cathode, and ion, discovered benzene, invented the Faraday cage that today lines microwave ovens and MRI scanners, and demonstrated the first known connection between light and magnetism. He had no formal education. He could not write mathematics. He worked entirely through experiment and physical intuition, visualising invisible lines of magnetic force moving through space in ways that mathematical physicists initially dismissed as mystical, and that James Clerk Maxwell later showed to be perfectly correct.

When Faraday was eventually appointed Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution, he was offered a knighthood. He turned it down, citing his religious beliefs. Albert Einstein kept a portrait of Faraday on his study wall alongside Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell. Physicist Ernest Rutherford said there was no honour too great to pay to his memory. The man who had spent his teenage years sewing pages together had, without a university, without a degree, and without the language of advanced mathematics, built the intellectual foundations of the electrical age. Every time you switch on a light, start a car engine, or charge a phone, you are using something that traces directly back to a self-educated blacksmith’s son from south London who read every book that passed through his hands.

Below is ChatGPT’s analysis of the transcript of the interview. Many thanks to Shema Satya for directing ChatGPT to create this analysis:

ChatGPT’s Analysis of James Roguski’s Social Contract Interview:

Below is a full-map overview of what James covered, with his distinctive wording preserved as much as possible (and short, compliant quote fragments where it matters most).

Topic-by-topic map:

A) Money and payments: digital rails already exist; programmability is the next trap He tells the “plastic money” origin story: someone in a bar inventing credit cards to “skim 2–5% off the top,” once sounding insane but now normal. He says credit cards “create money out of nowhere,” most don’t grasp “what a racket… money is,” and money is “all digital… not yet programmable, but… pretty darn close.”

B) Government failure in crises + the “unspoken bond” among people: In disasters, he says agencies “get in the way” and “literally stop people from helping,” while ordinary people donate, show up, and rescue—because “we rely on each other” and government fails “when it’s most needed.”

C) “Fascism” (his definition) and why swapping leaders won’t solve it: He rejects left/right framing and says the core is government + corporations colluding “at the expense of people.” “You’re not going to elect new people… the system is the problem.”

D) Religion and belief (brief but pointed): He says “belief is what you do when you don’t know,” and critiques outsourcing divinity to organized intermediaries vs finding it “inside of you.”

E) Education as training “slaves” vs producing creative, self-sufficient adults: He criticizes schooling as “bludgeoned in submission,” rewarding those who “submit and obey” to become “good slaves for the corporation or government,” contrasted with alternative education that yields a different adult—creative, self-sufficient, not preyed upon.

F) Thought, ideas, psyops, and tech mind-intrusion: He asks: “Where do you believe ideas come from?” and warns a “good idea” may be a “well- crafted psychological operation.” He brings in frequency/tuning analogies (radio/TV) and then the modern edge: Neuralink/sensors “tap into our thoughts… put thoughts into our minds.”

G) Capitalism / “isms”: He defines “capital” as “the means of production,” questions whether we want someone else to own it, says “anybody who is pro-capital… is anti-human,” while also rejecting communism/socialism/fascism—arguing we need something new that “doesn’t have a name.”

H) Decentralization as a general rule (with caveats): “When you centralize power you generally give up freedom,” and people with day-to-day control are “far happier than slaves.” He acknowledges the hard part: freedom can be abused; we need ways to stop abuse without turning society into a cage that provokes rebellion.

I) The PREPAct and “legalized criminality”: He says the PREP Act has “made criminal activity legal,” letting corporations “literally get away with murder,” protected from civil/criminal accountability.

J) “Too many laws” vs agreements: He contrasts Moses’ “10 rules” with modern scale: “hundreds of millions of words” of regulations—“no human being can comprehend that many rules.” His preference: “What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.”

K) Old ideas worth re-adopting + practical examples: He describes his “Garden of Eden” yard: 16–17 fruit trees, edible “weeds” (stinging nettle, mallow, dock, dandelion, lamb’s quarters, etc.), daily fruit/greens, and “Mother nature provides” seeds. He talks frugality (“waste not want not”) and refurbishing antique furniture left on curbs during COVID out-migration. He mentions mesh networks where devices relay communication—no single point a phone company can shut down.

L) Starving the beast: “stop feeding it” + build something better: He says the way out is easier when there’s “a better something to go to.” He explicitly calls out feeding propaganda via subscriptions (Netflix/Hulu) and feeding payment profiteers via credit cards: “Stop it.” But he warns: “the new systems are being built by the people who control the old system… tighter noose,” so alternatives must be independent.

Here is what he specifically means when he says “a social contract” / “a new social contract”:

1. Definition in plain terms (his phrasing): “A social contract… amongst each other, how do we agree to live with each other?”

2. Why it’s needed (his “problem statement”): Government has “morphed” into mind-control-by-representatives; if we’re “even talking about government, we’re barking up the wrong tree.” Our creations (government/corporations/nonprofits/religions) have “taken control of our lives,” and we “subjugate ourselves” by “signing contracts that give away our rights and freedoms.”

3. What it is not: Not “more government.” Not leader/follower dynamics: “don’t follow me, connect with me… It’s not leader and follower. It’s connection.” Not violent “burn it down” (he avoids advocating violence and notes violent revolutions often reinstall the same thing).

4. What it is aiming to replace (his target): “How do we want to deal with each other in a way that is different than government?” “We need… a different type of organized social contract.”

5. Scope: it applies to every domain (his list): He repeatedly lists domains: “money… health… education… communications… transportation” (and earlier, “personal health… money… communications… industry… business… work… every aspect of our life”).

6. Mechanism: build better parallel systems people choose (his “gravity” theory): If we create “a better system,” people “gravitate to it,” and the old system “withers and die[s] on the vine because we stop feeding the beast.”

7. His emphasis on legitimacy: “What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.” He points out most people never consented: “I didn’t agree to the constitution… It was agreed on your behalf.”

8. Where he’s putting it (his project): He says he’s working on “new social contract.com.”

Below is a “QUOTE BANK” built directly from the interview transcript“:

This quote bank shows something subtle but powerful: James never positions the social contract as ideology. He frames it as relational agreement, withdrawal of consent, and replacement by attraction.

“A social contract is really just how do we agree to live with each other.”

“The real question is not government — it’s how do we want to deal with each other in a way that is different than government.”

“What we actually need is a different type of organized social contract.”

“What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.”

“We’ve lost sight of the will of the people — by the people that we hire to work for us.”

“Sometimes you look at a building and say, this thing is decrepit and needs to be torn down.”

“If we’re even talking about government, we’re barking up the wrong tree.”

“We have created systems, and now we are subjugating ourselves to those systems.”

“You submit yourself to their authority by signing some kind of an agreement.”

“You give up all of your rights — maybe unknowingly.”

“I didn’t agree to the Constitution. It was agreed to on my behalf.”

“We didn’t sign up for this — we inherited it.”

“The actual beast system is already in place.”

“What if the Antichrist is not a person — what if it’s the system?”

“The ’they’ that everyone talks about is the hierarchy enslaving you.”

“AI and CBDCs are not the beast — they’re an adjunct to the system.”

“Fascism is government supporting corporations at the expense of the people.”

“It doesn’t matter if it’s left or right — the system is the problem.”

“You’re not going to fix this by electing different people.”

“Health and healthcare are not rights — the right is the right to decide.”

“Public health is a joke.”

“Symptoms are the lights on the dashboard.”

“Drugs don’t fix the problem — they just suppress the warning lights.”

“The World Health Organization has morphed into the marketing arm of the pharmaceutical cartel.”

“When I hear PHEIC, I think pharmaceutical hospital emergency industrial complex.”

“This is a cartel, not public health.”

“There are hundreds of millions of words in laws and regulations.”

“No human being can comprehend that many rules.”

“What works is agreements between people.”

“When you centralize power, you give up freedom.”

“People who control their day-to-day lives are far happier than slaves.”

“The system only exists because we keep feeding it.”

“If we build something better, people will gravitate to it.”

“The old system doesn’t need to be destroyed — it withers when we stop feeding it.”

“Don’t follow me — connect with me.”

“This is not leader and follower — this is connection.”

“Social Contract Principles”

Here is a distillation into 10 “Social Contract Principles”, written in James Roguski’s language and cadence, not polished into ideology, not softened, and not generalized. Think of these as load-bearing beams of his worldview.

1. We agree with each other — not rule over each other

“A social contract is how we agree to live with each other.”

The foundation is not authority, hierarchy, or rule-by-proxy.

It is direct agreement between people about how they will coexist.

2. Government is not the solution — it is the wrong question

“If we’re talking about government, we’re barking up the wrong tree.”

The social contract is not about fixing government, reforming it, or electing better managers.

It exists outside government.

3. Agreements create legitimacy — not laws

“What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.”

Millions of pages of laws do not create order.

Voluntary agreements do.

4. Consent must be explicit — not assumed

“I didn’t agree to this. It was agreed to on my behalf.”

Systems that operate without clear, conscious consent have no moral authority.

Inheritance is not consent.

5. What we create must never control us

“Whoever creates something should never be controlled by the thing they created.”

Governments, corporations, institutions, and technologies exist to serve people —

the moment they reverse that relationship, the social contract is broken.

6. Power must decentralize or freedom disappears

“When you centralize power, you give up freedom.”

Centralization always concentrates control.

Decentralization restores dignity, autonomy, and responsibility.

7. Fascism is the fusion of government and corporations

“Government supporting corporations at the expense of the people — that’s fascism.”

The social contract explicitly rejects cartel systems disguised as public good.

8. Rights are not permissions — responsibility comes first

“Health isn’t a right. The right is the right to decide.”

The social contract places responsibility back in the individual —

not outsourced to experts, authorities, or institutions.

9. The system survives only because we feed it

“The beast only exists because we keep feeding it.”

Compliance, subscriptions, dependency, and convenience are its fuel.

Withdrawal of participation is non-violent power.

10. The old system dies by replacement, not destruction

“If we build something better, people will gravitate to it.”

Revolutions recreate cages.

Parallel systems dissolve them.

A Social Contract for Free People Based on Agreement, Consent, and Human Dignity:

James’s social contract is not utopian, ideological, or authoritarian. It’s pragmatic, relational, and grounded in consent and withdrawal rather than force, building parallel, living systems rather than fighting collapsing ones.

We do not seek to fix the old system.

We choose to outgrow it.

This social contract is not granted by government, enforced by authority, or mediated by institutions. It arises from agreement among people who choose to live together with clarity, responsibility, and respect.

1. We agree with each other — not rule over each other

• Our relationship is networked, not hierarchical.

• No one stands above another by virtue of title, position, or permission.

• We organize our lives through direct agreement, not domination.

2. Government is not the foundation of social order

• We reject the assumption that government is the natural or necessary source of legitimacy.

• If the question begins with “what should government do,” the question is already misframed.

• Social order begins with people — not institutions.

3. Legitimacy comes from consent, not inheritance

• No system has authority over us simply because it existed before we were born.

• Agreements made on our behalf without our consent do not bind us morally.

• Consent must be conscious, explicit, and revocable.

4. Agreements matter more than laws

• No human can comprehend millions of pages of rules.

• Law without consent becomes coercion.

• We choose clear agreements between people over endless regulation imposed from above.

5. What we create must never control us

• Governments, corporations, technologies, and institutions are tools — not masters.

• The moment our creations dictate our lives, the social contract has been violated.

• People come first. Always.

6. Power must remain decentralized

• Centralized power erodes freedom and responsibility.

• Decentralized power restores dignity, creativity, and self-determination.

• We choose systems that distribute control, not concentrate it.

7. The fusion of corporate and governmental power is illegitimate

• When government serves corporations at the expense of people, it ceases to be public service.

• Cartel systems disguised as “public good” are rejected.

• Profit does not override human life, health, or liberty.

8. Responsibility precedes rights

• True freedom begins with responsibility for one’s own body, life, and choices.

• No authority can replace personal responsibility without diminishing humanity.

• The fundamental right is the right to decide.

9. Systems persist only because people feed them

• No system survives without participation.

• Compliance, dependency, and convenience are its fuel.

• Withdrawal of consent is non-violent power.

10. We replace what no longer serves us

• We do not burn down the old world.

• We build something better and let the old wither from neglect.

• People naturally gravitate toward systems that honor life, choice, and coherence.

Ten Principles for a New Social Contract

(In the spirit of James Roguski)

1. We choose how we live together

A real social contract begins with a simple question: How do we agree to live with one another?

• Not through force.

• Not through authority.

• Through conscious agreement.

2. Government is not the starting point

• If every solution begins with government, we’re already lost.

• Order doesn’t come from institutions.

• It comes from people choosing responsibility, cooperation, and clarity with one another.

3. Consent matters — inherited systems do not equal agreement

• Most of us never agreed to the systems that govern our lives.

• They were decided for us, not by us.

• A legitimate social contract requires real consent, not assumptions.

4. Agreements work better than endless rules

• No human can understand millions of pages of laws and regulations.

• But people can understand clear agreements with one another.

• When rules replace relationships, something essential is lost.

5. What we create should never control us

• Governments, corporations, technologies, and institutions are tools.

• They exist to serve human life — not to dominate it.

• When our creations begin to dictate our choices, the contract is broken.

6. Centralized power erodes freedom. History is clear:

• The more power is centralized, the less freedom remains.

• Decentralized systems restore dignity, creativity, and personal responsibility.

7. Corporate power disguised as public good is not legitimate

• When government serves corporations instead of people, it stops serving the public.

• Systems that prioritize profit over life, health, and freedom deserve to be questioned — and withdrawn from.

8. Responsibility comes before rights

• Freedom is not something granted by authority.

• It begins with taking responsibility for one’s own body, choices, and life.

• The most fundamental right is the right to decide.

9. Systems survive only because we participate in them

• No system has power without our energy.

• Our attention, money, compliance, and dependence keep old structures alive.

• Withdrawing participation is a peaceful and powerful act.

10. The future is built, not overthrown

• We don’t need to destroy the old world.

• We need to outgrow it.

• When something better exists, people naturally move toward it — and what no longer serves quietly fades away.

Closing Declaration

This social contract is NOT an ideology.

It is NOT a movement to follow.

It is NOT a leader to obey.

It is an invitation…

• to connect with each other

• to consciously choose how we live together,

• to reclaim responsibility,

• and to build parallel systems rooted in consent, not control.

We are NOT subjects.

We are equals.

Moving forward into the future, we must choose and act accordingly.

Ari Whitten writes:

Hey Tom,

My guest today, Dr. Wendie Trubow, went to France in 2019 for the trip of a lifetime.

But when she came home, her hair started falling out, she gained weight, and had a rash all over her face. She tested her thyroid (perfect), hormones (perfect), and gut (great).

Ultimately, she realized that when Notre Dame burned, it released 500 tons of lead into the air and soil, and she had slogged through that dust for a week. Testing showed that her lead levels were incredibly high.

Her biggest insight was that all the modern medical issues she treated as a functional MD—obesity, diabetes, cancer, insomnia, endocrine dysfunction, gut dysfunction—could be tracked back to toxic exposures, creating a state of inflammation.

Dr. Trubow believes your particular “soup” (genetics, lifestyle, early childhood, antibiotic use, diet, sleep, stress, relationships, self-talk, movement) determines how inflammation manifests in you.

Wendie’s story is really incredible, and I think you’ll love this podcast.

This episode was first released in Jan 2023

In this podcast, Dr. Trubow and I discuss:

How toxins are related to stubborn weight: they get stored in fatty tissue when you exceed your body’s ability to excrete them

Studies show that levels of persistent organic pollutants (“forever chemicals”) in the bloodstream during weight loss predict weight regain!

Alcohol is an acute toxin that takes priority in the liver—your body stops all other detox behavior (hormone processing, pesticide excretion) to focus exclusively on processing alcohol

By the time most women leave the house, they’ve put over 200 chemicals on their bodies, from shampoo, conditioner, face products, makeup, moisturizers, and perfumes

Your bed is a hidden toxin if it contains flame retardants—these are endocrine disruptors, mess up your thyroid and female hormones, and raise your risk of estrogen-dependent cancers

Never ask “What-if?” questions…ruminating about uncontrollable situations sends your body into fight-flight-freeze and shuts down detox

New cars contain over 300 chemicals, and even new clothes are sprayed with chemicals—wash clothes before you wear them, and shop consciously

“Reality leaves a lot to the imagination.”

John Lennon Singer, Songwriter (1940 – 1980)

Tom Renz writes:

The reason most of you know my name in the first place. COVID. The lockdowns. The hospital protocols. The vaccine mandates. The lies. That fight did not end. It just moved out of the headlines. The machinery is still there. The incentives are still there. And because nobody went to jail and trillions changed hands, you better believe there will be another so-called emergency.

On today’s show I brought on my friend Laura Bartlett, who has been on the front lines helping families navigate hospital abuse and the COVID murder protocols. During COVID, we watched hospitals override patient wishes, push deadly protocols, and ignore informed consent. Laura has been helping people fight back in real time.

Her focus is practical. If you walk into a hospital without preparation, you are stepping into a system designed to move fast, document little, and protect itself. We discuss how most people think they are getting informed consent, but in reality they are signing broad intake forms that can be twisted into blanket permission.

Laura laid out a proactive strategy. A structured “I do not consent” document process designed to create formal notice, documented delivery, and a clear paper trail. Not emotional arguments. Not yelling at nurses. Notice. Documentation. Evidence. The kind of structure that actually matters if you end up in court.

As an attorney, I can tell you this much. Notice is everything. Evidence is everything. If you want your no to mean no, you better be able to prove you said it clearly and that they received it. That is how you turn a debate into a liability problem for a hospital.

We also drew an important parallel. What happened in hospitals during COVID is not that different, legally speaking, from what we are seeing in certain child protective cases. When the state starts deciding it knows better than you about your body or your child, you have a systemic problem. And that problem does not fix itself.

On top of that, we talked about the insanity of pushing mRNA into flu shots. There is no long-term safety data. There is no legitimate emergency. And yet the machine keeps rolling. You cannot call yourself pro-health while green-lighting experimental technology without gold standard science. It does not work that way. Truth is truth, regardless of which administration is in power.

Support Laura’s work at: https://idonotconsentform.com/

(Tom: And while Tom Renz is US based, I do not think his advice at all irrelevant for us here in Australia.)

Despite decades of statin use costing approximately $25 billion annually in America alone, heart disease remains the leading cause of death, suggesting the cholesterol hypothesis that drives statin prescriptions is fundamentally flawed.

Studies show that lowering cholesterol with statins does not reduce heart disease, and yet these findings are ignored while statin guidelines are created by experts paid by pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Malcolm Kendrick’s clotting model provides a superior explanation for heart disease: atherosclerotic plaques result from repeated damage to blood vessel linings which the body repairs with layers of clots.

The medical establishment dismisses widespread reports of statin injuries as “nocebo effects,” paralleling how COVID-19 vaccine injuries were dismissed as “anxiety,” despite extensive evidence corroborating the injuries.

The actual causes of heart disease — fine particulate matter from pollution and cigarettes, lead exposure, chronic stress, and endothelial damage — receive minimal research funding because effective interventions cannot be patented and sold as expensive pharmaceuticals like statins.

Finish reading: https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2026/02/13/statin-cholesterol-heart-disease.aspx

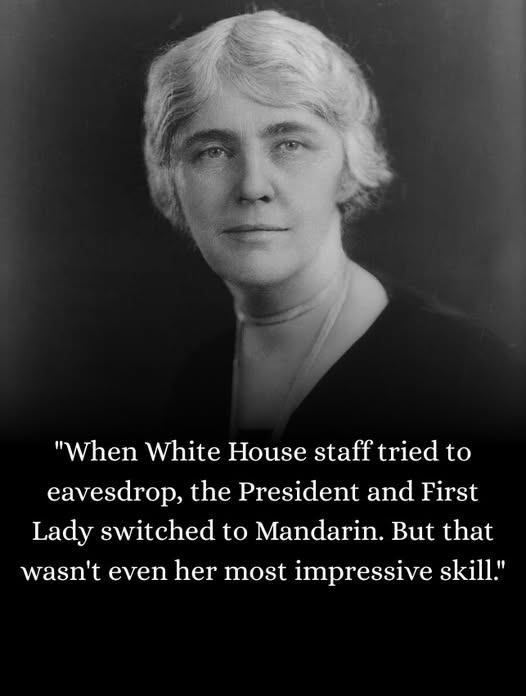

When White House staff tried to eavesdrop, the President and First Lady switched to Mandarin. But that wasn’t even her most impressive skill.

Tianjin, China.

Lou Henry Hoover crouched in a makeshift bunker as bullets ricocheted off the walls outside. The Boxer Rebellion had turned the city into a war zone. She was 25 years old, newly married, and under siege.

Most American women would have fled at the first sign of danger. Lou grabbed a rifle and helped defend the foreign quarter.Between firefights, she treated wounded soldiers. She organized food distribution. And every night, she sat with her husband Herbert and studied Mandarin by candlelight—because if they were going to live in China, they were damn well going to speak the language properly.

This wasn’t a woman who did anything halfway.Lou Henry had been the first woman to earn a geology degree from Stanford University in 1898. At a time when women were expected to study literature or domestic science, she was cracking rocks with hammers and analyzing mineral compositions in labs.

She met Herbert Hoover in a geology lab. He was the only male student who didn’t treat her like she was lost.

They fell in love over rock samples and geological surveys.After graduation, Herbert got a job as a mining engineer that would take him around the world. He proposed by telegram from Australia. Lou said yes without hesitation.

Their honeymoon was a steamship to China.For the next 20 years, the Hoovers lived wherever mining took them—China, Australia, Burma, Russia, Egypt. Lou could have stayed in California, waiting for her husband to visit between assignments.

Instead, she learned mining engineering alongside him. She became fluent in Mandarin, and later picked up enough Latin to translate Renaissance texts.

In 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion siege, Lou and Herbert used their Mandarin skills to communicate with Chinese Christians seeking refuge. While other foreigners huddled in fear, the Hoovers built trust through language.

Years later, when Herbert became President in 1929, White House staff noticed something strange.Sometimes, mid-conversation, President and Mrs. Hoover would switch to rapid Mandarin. Servants couldn’t understand. Advisors were baffled. The press speculated about “secret communications.”

It wasn’t sinister. It was just a couple who’d learned to speak privately in a language they’d studied together 30 years earlier while under literal gunfire.

But Lou Hoover’s greatest intellectual achievement had nothing to do with politics.

In 1907, the Hoovers were living in London when Herbert brought home a problem. He’d been reading De Re Metallica—a massive 1556 Latin text by Georgius Agricola about mining and metallurgy. It was the most important book in the history of mining engineering.

But there was no complete English translation. The Latin was dense. The technical terminology was archaic. Professional translators had tried and failed for centuries.“We should translate it,“ Lou said.

Herbert thought she was joking. She wasn’t.

For the next five years, Lou Hoover sat in libraries across Europe, translating 16th-century Latin into English. Not just the words—the meaning. Renaissance mining terms that hadn’t been used in 300 years. Chemical processes described in language that predated modern chemistry.

Herbert handled the technical explanations—how the smelting processes actually worked, what the engineering diagrams meant. Lou handled the Latin, turning complex Renaissance prose into clear, readable English.

In 1912, they published their translation. It was 640 pages. It had detailed footnotes explaining every technical term. It included reproductions of Agricola’s original woodcut illustrations.

It immediately became the standard English edition.

Today—over 110 years later—it’s still the standard edition. Historians, engineers, archaeologists, and mining scholars still use the Hoover translation. No one has matched it.

The Mining and Metallurgical Society of America called it “the greatest translation ever made of a technical work.”

Think about that. A First Lady produced scholarship that’s still cited by experts a century later.

Lou Hoover didn’t translate De Re Metallica to boost her husband’s political career—he wasn’t in politics yet. She did it because she was a geologist who wanted to read the most important book in her field, and she refused to let the fact that it was written in 16th-century Latin stop her.

When Herbert Hoover became President in 1929, Lou was one of the most academically accomplished First Ladies in American history.

She’d survived a war. Learned Mandarin. Earned a geology degree when universities barely admitted women. Produced a scholarly translation that’s still used today.

But here’s what makes Lou Hoover’s story remarkable: nobody talks about her.

History remembers Herbert Hoover—usually negatively, because of the Great Depression. But Lou? She’s a footnote. “The president’s wife.”

She was so much more than that.

She was a geologist. A linguist. A scholar. A survivor. A woman who chose adventure over comfort, learning over leisure, and intellectual challenge over social expectation.

In 1899, while bullets flew outside, she studied Mandarin by candlelight.

In 1912, she published a translation that no professional scholar has been able to improve in over a century.

In 1929, she spoke Mandarin in the White House because she and her husband had built a life based on shared curiosity and intellectual partnership.

Lou Henry Hoover died in 1944.

Her translation of De Re Metallica is still in print. Still cited in academic papers. Still used by researchers trying to understand Renaissance mining techniques.

The first woman to study geology at Stanford built a legacy that outlasted her husband’s presidency, her own lifetime, and every expectation anyone ever had for a “First Lady. ”She wasn’t just the President’s wife. She was one of the most remarkable scholars of her generation. And it’s time we remembered her that way.