She sat quietly knitting while they called her people savages. Then she stood up and used their own words to destroy them.

Juneau, Alaska. February 8, 1945.

The Alaska Territorial Legislature chamber was crowded and tense. In the gallery sat dozens of Native Alaskans—Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian—who had traveled to the capital for this moment. They came for a single law. The Anti-Discrimination Act. A bill that would make it illegal to post signs reading “No Natives Allowed.” That would let them enter any restaurant, any hotel, any theater without being turned away.

A law that would recognize them as equal citizens in their own ancestral homeland.

But first, they had to endure a hearing where white senators explained why Native people didn’t deserve equal rights.

This was 1945. Ten years before Rosa Parks. Nineteen years before the federal Civil Rights Act. Most Americans don’t know that the first anti-discrimination law in United States history was won in Alaska by a Tlingit woman facing down a room of hostile legislators.

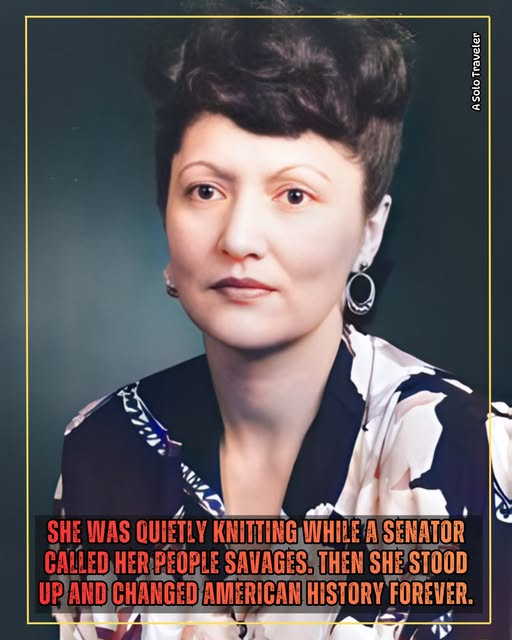

Her name was Elizabeth Peratrovich.

And she was about to deliver one of the most devastating responses in American political history.

One senator after another rose to oppose the bill. They argued that the races should remain separate. That integration would cause problems. That Native people weren’t ready for full equality.

Then the insults became personal.

One senator complained openly that he didn’t want to sit next to Native people in theaters because of how they smelled. Another suggested that Native peoples lacked the sophistication to deserve equal treatment.

The Native people in the gallery sat in dignified silence. They’d heard these attitudes their entire lives—but never so brazenly, never in an official government chamber, never while forced to listen without recourse.

Then Senator Allen Shattuck stood. He was among the most vocal opponents of the bill. He looked directly at the Native people in the gallery, his voice dripping with contempt.

“Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites with five thousand years of recorded civilization behind us?”

The room went silent.

He had just called them savages. Primitives. People barely evolved enough to desire equality with civilized whites.

In the back of the chamber, Elizabeth Peratrovich was knitting. She was thirty-three years old, mother of three, and president of the Alaska Native Sisterhood. She was known for her composure, her quiet dignity even in the face of injustice.

She set her knitting needles down.

She stood.

Elizabeth hadn’t come prepared to testify. She was simply a Native woman who had spent her life seeing signs in windows telling her she wasn’t welcome. Who had been turned away from hotels. Who watched her children learn they were considered less than human in their own homeland.

She walked to the front of the chamber. Every eye followed her. The legislators who had been sneering moments before now watched in heavy silence.

She looked directly at Senator Shattuck. She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t show anger. Her tone was measured, controlled, devastatingly clear.

“I would not have expected that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind gentlemen with five thousand years of recorded civilization behind them of our Bill of Rights.”

The impact was immediate.

She had taken Shattuck’s insult—”barely out of savagery”—and turned it into a weapon. She used his claim of superior civilization to expose his complete lack of it.

A defensive murmur went through the opposition. They knew they’d been caught. Exposed. Shamed.

But Elizabeth wasn’t finished.

She described what it meant to see signs comparing her people to dogs. To have her children ask why they weren’t allowed in certain stores. To be treated as unwelcome in lands their ancestors had inhabited for thousands of years before any white settler arrived.

Then came what opponents thought would trap her. A senator asked skeptically whether a law could truly change people’s hearts and stop discrimination.

Elizabeth’s response became legendary.

“Do your laws against larceny and murder prevent those crimes?” she asked calmly. “No law will eliminate crimes, but at least you as legislators can assert to the world that you recognize the evil of the present situation and speak your intent to help us overcome discrimination.”

Silence.

She had dismantled every argument. She had proven she understood law, morality, and civilization better than the senators who claimed millennia of it.

The Native people didn’t need education from white legislators. The white legislators needed education from Elizabeth Peratrovich.

When the vote was called, the Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945 passed eleven to five.

The first anti-discrimination law in United States history.

Not in New York. Not in California. In Alaska. Because a Tlingit woman refused to remain silent when called a savage.

The law prohibited discrimination in public accommodations. It made “No Natives” signs illegal. It declared that Alaska would not tolerate racial discrimination.

Nineteen years before the federal Civil Rights Act. Ten years before Rosa Parks became a household name.

Yet most Americans have never heard of Elizabeth Peratrovich.

We learn about Rosa Parks, as we should. We study Martin Luther King Jr., the March on Washington, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. These stories deserve to be taught and remembered.

But the woman who won the first anti-discrimination law in American history? The woman who faced down racist senators and won? She remains virtually unknown outside Alaska.

Why? Because Alaska wasn’t the South where national media focused. Because Native American civil rights struggles didn’t capture headlines the way other movements did. Because Elizabeth didn’t have a national platform or massive organization—just her dignity and her refusal to accept injustice.

But Alaska remembers.

February 16th is Elizabeth Peratrovich Day, an official state holiday. Schools and government offices close. In 2020, plans were announced to feature her on the dollar coin. In Juneau stands a bronze statue of Elizabeth, captured in quiet dignity—just as she stood in that chamber in 1945.

Yet beyond Alaska, her story remains obscure. That’s tragic, because what Elizabeth proved was fundamental.

Civilization isn’t measured by how many years your history spans. It’s not measured by monuments or recorded achievements or military conquests.

It’s measured by how you treat the vulnerable. By whether you uphold dignity or destroy it. By whether you use law to protect people or to oppress them.

Senator Shattuck claimed five thousand years of civilization. Elizabeth Peratrovich proved he had none.

Because what’s civilized about “No Dogs, No Natives” signs? What’s civilized about denying people access to public spaces in their own ancestral homeland? What’s civilized about a government official calling people savages?

Nothing.

Elizabeth didn’t need five thousand years of history. She needed moral clarity and courage.

She weaponized their own claims against them. She demonstrated that the supposed “savage” in the room understood America’s founding principles better than the “civilized” senators did.

And she won.

Elizabeth Peratrovich died in 1958 at age forty-seven. She didn’t live to see the federal Civil Rights Act. She didn’t see her image on coins or statues erected in her honor.

But she lived long enough to see “No Natives” signs removed throughout Alaska. She lived to know her children could enter any business in Juneau without being turned away. She lived to see the law of an entire territory changed because she refused to be silent.

That’s not just one woman’s victory. That’s proof that dignity is powerful. That moral clarity can defeat bigotry. That sometimes changing history requires one person willing to stand, set down their work, and speak truth to power.

The senators thought they had civilization on their side. They thought their recorded history gave them authority.

Elizabeth Peratrovich taught them that civilization isn’t inherited. It’s earned every single day by how you treat people.

She was knitting quietly while senators called her people savages.

Then she reminded them what civilization actually means.

And she won the first anti-discrimination law in United States history.

Elizabeth Peratrovich deserves to be as famous as any civil rights leader in American history.

Now you know her name.