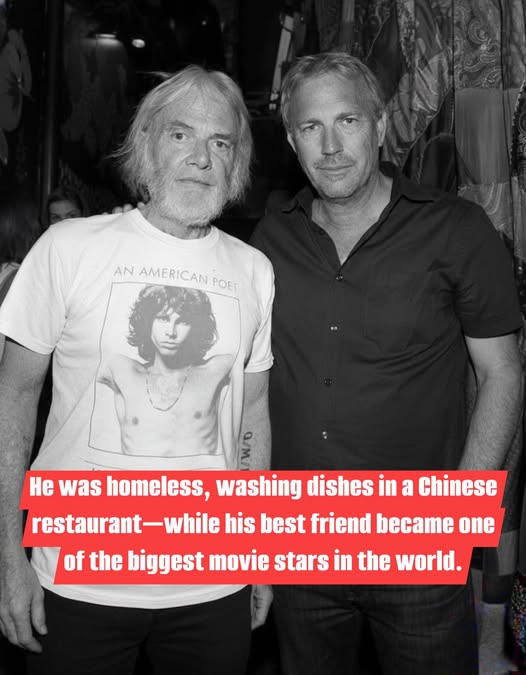

He was homeless, washing dishes in a Chinese restaurant—while his best friend became one of the biggest movie stars in the world.

That friend would later make a single decision that changed both their lives forever.

In the late 1970s, Michael Blake arrived in Hollywood with nothing but a typewriter and an unshakable belief that stories mattered. By 1981, he crossed paths with another struggling actor named Kevin Costner. No fame. No money. Just rejection letters and long days chasing auditions that went nowhere.

They were outsiders together. And that shared struggle welded them into friends.

In 1983, Blake wrote a small, scrappy film called Stacy’s Knights. Costner starred. The movie failed quietly. No buzz. No future.

Their friendship survived.

Then everything changed—except for Blake.

Kevin Costner’s career exploded. One role led to another. Suddenly, doors opened wherever he went. Instead of leaving his old friend behind, Costner tried to pull him forward. He set up meetings. He praised Blake’s talent. He put his own reputation on the line.

But every report came back the same.

“I sent him on a lot of jobs,” Costner later said,

“and every report that came back was that he pissed everybody off.”

Blake was brilliant—but difficult. Bitter. Angry. Rejection had hardened him. He blamed executives. Studios. The system. Everyone but himself.

Costner watched his friend self-destruct.

One afternoon, the frustration boiled over. Costner grabbed Blake and shoved him against a wall.

“Stop it!” he shouted.

“If you hate scripts so much, quit writing them!”

The moment shattered everything. It felt like the end.

A week later, Blake called.

He had nowhere to sleep.

Could he stay?

Costner said yes.

For nearly two months, Michael Blake lived on Kevin Costner’s couch. He read bedtime stories to Costner’s daughter. He stayed up late every night, pouring anger and heartbreak onto the page. Writing wasn’t just hope anymore—it was survival.

Eventually, the family needed space. Blake packed what little he owned and drove to Bisbee, Arizona.

There, far from Hollywood, he washed dishes in a Chinese restaurant for minimum wage. Some nights he slept in his car. Other nights on borrowed couches.

But every night, he wrote.

He carried a story he couldn’t let go of—about a lonely Civil War soldier who finds belonging among the Lakota Sioux. A Western—when Hollywood said Westerns were dead. Expansive—when studios demanded safe, small films. Risky—when executives feared anything different.

Costner and producer Jim Wilson believed in it. But they knew the truth.

No studio would touch it.

Their advice was simple:

Turn it into a novel first.

Blake did.

Thirty publishers rejected it.

Thirty.

Finally, in 1988, Fawcett released a modest paperback. The cover looked like a romance novel. When Blake asked about a second printing, he was told to write something else.

Costner never forgot the story.

When he finally read the book, he stayed up all night. He finished at sunrise and immediately called Blake.

“Michael,” he said,

“I’m going to make this into a movie.”

Costner paid $75,000 of his own money for the rights. He asked Blake to write the screenplay. He chose to direct—despite never directing before. And he would star in it himself.

Hollywood laughed.

They called it “Kevin’s Gate.”

A three-hour Western.

Subtitled Native dialogue.

A first-time director.

They predicted disaster.

Costner didn’t blink.

Filming lasted five brutal months in South Dakota—scorching heat, freezing cold, thousands of buffalo, hundreds of horses, live wolves. When the budget spiraled, Costner invested $3 million of his own money to finish the film.

On November 21, 1990, Dances with Wolves premiered.

Critics were stunned.

Audiences were moved.

The film earned $424 million worldwide—becoming the highest-grossing Western in history.

At the 63rd Academy Awards, it received twelve nominations.

It won seven.

Best Picture.

Best Director.

And Michael Blake—the man who once washed dishes and slept in his car—walked onto that stage in a tuxedo and accepted the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Years later, Costner said simply:

“We made the movie. And Michael won the Academy Award.”

Michael Blake died in 2015. His novel sold millions. Dances with Wolves was preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

But his real legacy isn’t the Oscar.

Or the box office.

It’s this:

He was rejected for years.

He burned bridges.

He hit rock bottom while his friend soared.

And he never stopped writing.

Dreams aren’t secured by perfect timing or easy applause.

Sometimes the difference between those who make it and those who don’t isn’t talent.

Sometimes it’s just refusing to quit.