A single ceramic resistor, no larger than a grain of rice, ruined the circuit. It was the wrong part. By every rule of electrical engineering, the device sitting on the workbench was a failure.

It was supposed to be a recorder. The engineer, a man named Wilson Greatbatch, was trying to build a machine that could listen to the sound of a human heart. He had reached into his tackle box of components, his eyes perhaps tired from the dim light, and pulled out a resistor marked with the wrong color bands.

He soldered it into place. He sealed the connection. He flipped the switch.

The machine did not record. It did not whine with static. Instead, it began to speak.

Blip. Silence. Blip. Silence.

The pulse lasted 1.8 milliseconds. The silence lasted exactly one second. Greatbatch stared at the oscilloscope, watching the green line spike and fall. He was not a doctor; he was an electrical engineer who tinkered in a barn behind his house. But he knew rhythm.

He realized the machine wasn’t listening. It was commanding. The mistake was beating exactly like a human heart.

It was 1956 in upstate New York. Greatbatch was working at an animal behavior farm, fixing instruments and building gadgets. He was an ordinary man with a garden and a family to feed. He had no medical degree and no funding.

But he had seen the alternative.

At the time, “heart block”—a condition where the heart’s electrical signals fail—was a death sentence. The only way to keep a patient alive was a painful, terrifying ordeal. Doctors used external machines the size of televisions, plugged into wall outlets. The electricity had to shock the chest through the skin, leaving burns. It was agony.

Worse, the patients were tethered to the wall. They could not leave the room. And if a summer thunderstorm knocked out the power grid, the machine stopped. The heart stopped. The patient died.

Greatbatch looked at his accidental circuit. It was small enough to hold in his hand. He realized that if he could shrink the battery and seal the unit, this didn’t need to be a machine on a cart. It could go inside the body.

He felt a cold resolve settle over him. He knew he had found the answer. He also knew that nobody would believe him.

In the 1950s, the medical rule was absolute: electronics do not go inside the human body. The logic was sound and fiercely defended by the establishment. The human body is a hostile, salty, wet environment. It corrodes metal in weeks. It rejects foreign objects violently.

Furthermore, batteries of that era were toxic. Putting a chemical power source inside a chest cavity was considered malpractice, if not manslaughter. The “standard of care” was the external machine. It was brutal, but it was understood. To suggest cutting a person open and leaving a machine inside them was seen as reckless science fiction.

This rule protected patients from quackery. It worked—until it met Wilson Greatbatch.

Greatbatch went home. He looked at his savings account. He had $2,000—enough to buy a house in some places, or feed his family for a year or two. It was his safety net.

He didn’t call a committee. He didn’t apply for a grant. He walked out to his barn, cleared a space on his workbench, and took the $2,000. He told his family they would have to grow their own vegetables to save money.

He quit his job. The safety net was gone.

For two years, the barn became his world. The struggle was quiet and monotonous. The problem wasn’t just the circuit; it was the packaging. How do you hide a machine from the body’s immune system?

He tried wrapping the components in electrical tape. The body fluids seeped through. He tried casting them in resin. The resin cracked. Every failure meant money lost, and the $2,000 was draining away like water.

Doctors laughed at him. When he showed his prototype to engineers, they pointed out that batteries would eventually run out. “Then you have to cut the patient open again, Wilson,” they said. “It’s too much risk.”

He kept soldering. The smell of burning rosin and melting tin filled the barn. He worked through the winter, heating the space with a wood stove. He modified the circuit to use less power. He found a new type of mercury battery. He found a surgeon, Dr. William Chardack, who was desperate enough to listen.

They tested the device on a dog. It worked for four hours. Then the body fluids shorted it out.

Greatbatch didn’t stop. He found a way to mold the device in a special epoxy used for boat hulls. He tried again. This time, it worked for days. Then weeks.

The pressure from the medical community remained. They argued that if the device failed, the doctor would be a murderer. Greatbatch argued that without the device, the patient was already dead.

In 1960, the theory faced reality. A 77-year-old man was dying of complete heart block. His heart beat so slowly that his brain was starving for oxygen. The external machines were failing him. There were no other options left.

Greatbatch handed over his device. It looked like a hockey puck wrapped in plastic.

The surgeons opened the man’s chest. They stitched the leads to the heart muscle. They tucked the device into the abdomen and closed the skin.

The room went silent. They waited for the rhythm.

Lub-dub.

The external machine was turned off. The wire was unplugged from the wall.

The man’s heart kept beating.

For the first time in history, a machine completely inside a human body was keeping a person alive. The patient didn’t die that day. He lived for another 18 months, eventually passing away from natural causes unrelated to his heart.

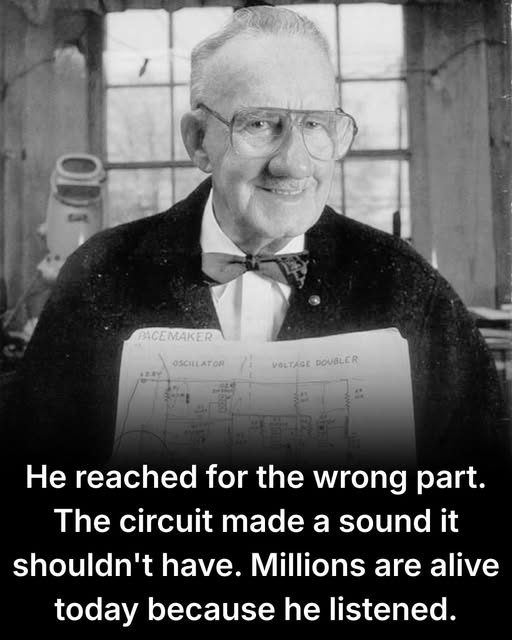

Greatbatch’s accidental resistor had become the implantable pacemaker.

Within years, the “reckless” idea became the gold standard. The device that experts said would kill patients began to save hundreds of thousands of them. Greatbatch didn’t stop there; he spent the next decade inventing a lithium battery that would make the devices last for years instead of months.

He never sought to become a medical tycoon. He held the patent, but he often licensed it in ways that allowed the technology to spread quickly. He was an engineer who solved problems.

Today, millions of people walk the earth with a small device in their chest, keeping time because an engineer in a barn reached for the wrong part, heard a sound, and refused to ignore it.

Sources: The New York Times archives (2011), Smithsonian Magazine (History of the Pacemaker), National Inventors Hall of Fame. Some details summarized.