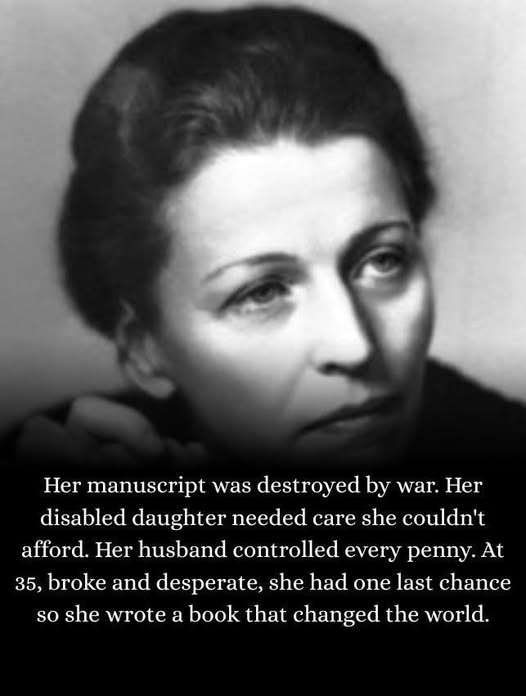

Her manuscript was destroyed by war. Her disabled daughter needed care she couldn’t afford. Her husband controlled every penny. At 35, broke and desperate, she had one last chance—so she wrote a book that changed the world.

Her name was Pearl S. Buck, and she would become the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. But first, she had to survive what would break most people.

Born in West Virginia in 1892, Pearl spent just three months in America before her missionary parents carried her to China. She grew up in Zhenjiang on the Yangtze River, speaking Chinese before English, playing with local children with her blonde hair hidden under a hat.

“I did not consider myself a white person in those days,” she later remembered.

She belonged everywhere and nowhere—a feeling that would haunt and define her entire life.

In 1917, she married John Lossing Buck and settled in rural China. Three years later, she gave birth to Carol.

Something was terribly wrong.

Carol couldn’t speak. She had violent tantrums lasting hours. She couldn’t learn basic tasks. Pearl’s husband withdrew completely, leaving her alone with a child whose condition no doctor could explain. Today we know Carol had phenylketonuria—a metabolic disorder causing severe developmental disabilities. In 1920, it was a mystery that felt like a curse.

Her husband controlled every penny of their money, forcing Pearl to beg for an allowance from her own teaching salary. He refused to return to America where Carol might get better care. Pearl realized with crushing clarity: she alone would be responsible for her daughter’s future, and she had no way to provide it.

Then came 1927.

During China’s civil war, the Nanking Incident erupted—a violent uprising that forced Pearl’s family to flee with only the clothes they wore. Soldiers ransacked their home.

In her attic workspace sat the only copy of her first completed novel—years of work destroyed in minutes.

The Red Cross evacuated them to Japan, then to a cramped rental in Shanghai shared with two other families. Her husband returned to work, leaving Pearl alone with the children in poverty.

She was 35. Her marriage was dying. Her daughter needed expensive lifelong care. Her manuscript was ash. She had nothing.

Most people would have surrendered.

Pearl started writing again—not from inspiration, but from desperation. Writing was her only path to financial independence, her only hope for Carol’s future.

She found a trade magazine listing three literary agents and wrote to all three.

Two rejected her immediately: “No American market for stories about China.”

The third, David Lloyd, said yes. He would represent her for 30 years.

In 1929, Pearl took Carol to America to find care. Touring institutions broke her heart—warehouses where disabled children were hidden and forgotten. She finally found the Vineland Training School in New Jersey, a place that seemed humane.

Leaving Carol there was, she said, the hardest thing she ever did.

To afford it, she borrowed money she had no idea how to repay.

Meanwhile, her first novel, East Wind, West Wind, was finally accepted—after 25 rejections. It was the last publisher on her agent’s list. One more rejection and it would have been withdrawn forever.

Pearl returned to China and began writing in a frenzy, driven by financial terror and creative urgency.

Three months later, The Good Earth was finished.

It told the story of Wang Lung, a Chinese farmer, and his wife O-Lan—ordinary people Pearl portrayed as fully human, complex, dignified, worthy of love. In 1930s America, where racism toward Chinese people was rampant, this was revolutionary.

When the Book-of-the-Month Club chose The Good Earth, Pearl received $4,000—enough for years of Carol’s care. She wept. For the first time in her life, she had security.

The book exploded. Nearly 2 million copies sold in the first year. It remained the bestselling novel of both 1931 and 1932. Pearl earned over $100,000 in eighteen months—an astronomical fortune during the Great Depression. She immediately secured $40,000 for Carol’s long-term care.

In 1938, Pearl S. Buck became the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

But her achievement went deeper than a prize. She had humanized Chinese people to Americans who’d been taught to see them as foreign and lesser. She built bridges across cultures through the simple power of storytelling.

She spent the rest of her life fighting for civil rights, women’s rights, and disability rights. She adopted seven mixed-race children. She wrote over 70 books. She founded Welcome House—the first international interracial adoption agency in America.

Pearl died in 1973 at 80. Carol outlived her mother, dying in 1992 at 72, having spent most of her life safely cared for at Vineland—exactly what Pearl had fought so desperately to ensure.

Pearl’s story teaches us something profound: sometimes our greatest work doesn’t come from comfort or privilege. It comes from necessity. From the determination to survive. From the fierce love that makes us refuse to give up.

She didn’t write The Good Earth because she felt inspired. She wrote it because her daughter needed her, and she had no other way forward.

And that desperation—that pure, undiluted love—produced one of the most important American novels of the 20th century.

Pearl S. Buck proved that when we’re fighting for the people we love, we’re capable of changing the world.