202 people died in one night.

Hundreds more were burned beyond recognition.

And one surgeon in Australia had already built the answer — years before anyone knew they would need it.

Saturday night. October 12, 2002.

Kuta Beach.

The streets were loud with music and laughter. Tourists filled the bars. It was the kind of tropical evening people replay in their memories for years — right up until the moment the sky turns into fire.

At 11:08 PM, a bomb exploded inside Paddy’s Pub.

Fifteen seconds later, a second and far more devastating car bomb detonated outside the Sari Club.

The blast wave shattered windows blocks away. The fireball swallowed entire rooms. When the smoke settled, 202 people were dead. Hundreds more were alive — but horribly burned.

Some had third-degree burns covering 40%, 50%, even 60% of their bodies. Clothing had melted into skin. Entire layers of tissue were gone.

The most critically injured were airlifted to Royal Perth Hospital in Western Australia.

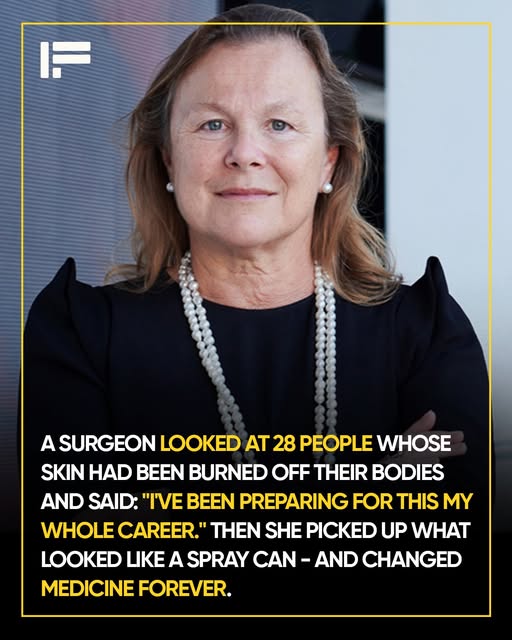

That’s where Dr. Fiona Wood walked into the ward.

And everything changed.

Severe burn treatment in the 1990s relied on one brutal truth: to repair destroyed skin, surgeons had to cut healthy skin from elsewhere on the body and graft it onto wounds.

For patients with limited unburned skin, this created a devastating cycle. To heal one injury, doctors had to create another.

Even worse, growing sheets of cultured skin in laboratories could take weeks. Critically burned patients often didn’t have weeks. Infection could claim them in days.

Fiona Wood, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon who had trained in the UK before moving to Australia, believed this wasn’t good enough.

Working alongside medical scientist Marie Stoner, she began refining an experimental approach: instead of transplanting sheets of skin, what if you could spray a suspension of a patient’s own skin cells directly onto the wound?

The concept became known as ReCell.

Take a tiny biopsy — sometimes smaller than a postage stamp — from surviving healthy skin. Process it rapidly. Create a suspension of living skin cells. Spray them evenly across the wound bed using a specialized device.

The cells would adhere, multiply, and regenerate skin in place.

To many in the field, it sounded improbable.

To Fiona Wood, it was necessary.

Throughout the 1990s, she and her team tested and refined the technique on smaller burn cases. Results showed faster healing and reduced scarring compared to traditional grafting alone.

Then Bali happened.

When Bali survivors began arriving in Perth, the scale of injuries overwhelmed conventional treatment plans.

These were not minor burns. These were catastrophic injuries.

Wood’s team moved immediately.

Small biopsies were taken from each patient’s remaining healthy skin. Lab teams worked around the clock to culture viable cell suspensions. Meanwhile, ICU teams fought infection and organ failure hour by hour.

When the first batches of cells were ready, Wood applied them using the spray device directly onto wounds that would otherwise require extensive grafting.

New epithelial growth began forming faster than traditional methods alone would have allowed.

Patients who might not have survived under older protocols began stabilizing. Healing times shortened. Scarring was reduced in many cases.

Survival rates among the critically burned Bali victims treated at Royal Perth were significantly higher than historical expectations for burns of that magnitude.

The world noticed.

What had begun as years of careful research inside a Perth lab had suddenly become a frontline lifesaving tool in a mass-casualty disaster.

In 2005, Fiona Wood was named Australian of the Year.

But recognition was never the objective.

ReCell technology evolved further and gained regulatory approval in multiple countries. It has since been used in civilian burn centers and military medicine — particularly for blast injuries and combat-related burns.

Today, spray-on skin technology and its descendants are part of modern burn care protocols globally.

Children injured in house fires heal with less extensive grafting. Industrial accident survivors recover faster. Military personnel receive treatment options that did not exist a generation ago.

The exact number of lives improved — or saved — because one surgeon refused to accept “good enough” is impossible to calculate.

But it spans continents.

Fiona Wood didn’t invent spray-on skin because she predicted an attack in Bali.

She built it because she saw suffering every day and believed medicine could do better.

For years, she tested, adjusted, refined, and defended an idea that sounded too ambitious.

Then one night, the crisis arrived.

And she was ready.

Real heroism is rarely dramatic in its early stages. It looks like research notes. Failed trials. Long lab hours. Skepticism from peers. Quiet persistence.

The explosion in Bali was sudden.

The preparation in Perth was not.

That’s the difference between reacting to disaster — and being prepared to transform it.