(Tom: We all owe this being a debt of thanks!)

He discovered how old the Earth was. Then he discovered something that could destroy us all.

For thousands of years, humanity wondered about the age of our planet. Religious texts offered one answer. Philosophers debated another. Scientists made educated guesses based on fossils and rock layers. But nobody actually knew.

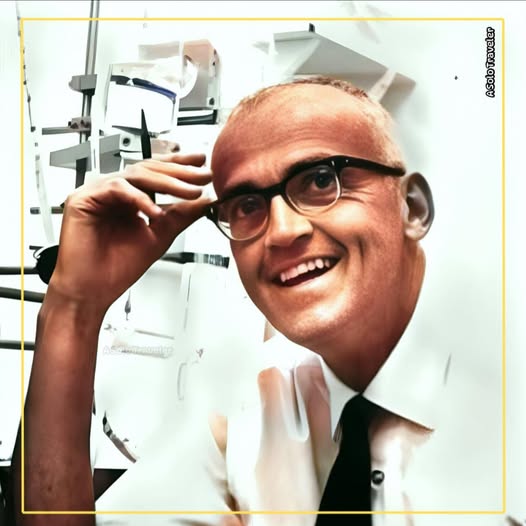

Until a quiet scientist named Clair Patterson figured it out in 1953.

He should have become instantly famous. His name should have appeared in every textbook. Instead, what he discovered next turned him into a target. He found himself standing alone against one of the most powerful industries on Earth, fighting a battle that would determine whether millions of children would grow up with damaged minds.

And for decades, almost nobody knew his name.

Patterson’s journey began in the late 1940s at the University of Chicago. He was a young geochemist with an impossible assignment: measure the precise amount of lead isotopes in a meteorite fragment called Canyon Diablo.

The theory was elegant—if he could measure these specific lead ratios accurately, he could calculate when the solar system formed, and therefore, when Earth was born.

But there was a problem that nearly broke him.

Every time he tried to measure the lead in his samples, the numbers were wildly inconsistent. One day high, the next day higher, never stable. His equipment seemed fine. His calculations were correct. Yet the data was chaos.

Most scientists would have given up or blamed the methodology. Patterson was different. He possessed an almost obsessive attention to detail and patience that bordered on stubborn madness.

One day, he realized something shocking: the problem wasn’t his rock sample. The problem was everything else.

There was lead everywhere. On the lab benches. In the air. Tracking in on people’s shoes. Floating as invisible dust particles. The entire world was contaminated, and it was sabotaging his measurements.

So Patterson did something unprecedented. He built the world’s first ultra-clean laboratory.

He scrubbed every surface until his hands bled. He sealed cracks in walls with tape. He installed specialized air filters. He made his assistants wear protective suits and wash repeatedly before entering. For years, he cleaned and refined and eliminated every possible source of contamination.

Finally, in 1953, he achieved it. He got a clean reading. He ran the numbers through a mass spectrometer, performed the calculations, and suddenly held an answer that no human in history had ever known:

4.55 billion years.

The Earth was 4.55 billion years old.

It’s said that in his excitement, he drove straight to his mother’s house in Iowa and told her he’d solved one of humanity’s oldest mysteries. The weight of not knowing had finally lifted.

But while building his clean room, Patterson had stumbled onto something far more disturbing.

Where was all this lead coming from?

Lead is naturally rare on Earth’s surface. It stays locked deep underground in mineral deposits. It doesn’t float freely in the air. It doesn’t coat laboratory tables. Yet it was everywhere—in quantities that made no sense.

Patterson began testing the world outside his lab. Ocean water. Mountain snow. Everywhere he looked, lead levels were hundreds of times higher than natural background levels.

And then he understood.

Since the 1920s, oil companies had been adding a compound called tetraethyl lead to gasoline. It prevented engine knock and made cars run smoother. But every car on every road was functioning as a poison dispersal system, spraying microscopic lead particles into the air with every mile driven.

Lead is a neurotoxin. It damages developing brains. It lowers IQ. It causes behavioral problems, aggression, and cognitive impairment. And an entire generation of children was breathing it every single day.

Patterson had to make a choice.

He was a geochemist. His job was studying rocks and isotopes, not fighting corporations or advocating for public health. He had stable funding and a promising academic career. He could have simply published his Earth-age discovery and moved on to the next project.

But he couldn’t unsee what he’d found.

In the mid-1960s, he published papers warning that industrial lead contamination was poisoning the environment and harming human health.

The response was swift and brutal.

The lead industry was massive, wealthy, and had no intention of losing billions in revenue. Their chief scientific defender was Dr. Robert Kehoe, who had spent decades assuring the public that environmental lead was natural and harmless. Kehoe was polished, well-funded, and had the backing of powerful corporations.

When Patterson challenged this narrative, the industry attempted to buy his silence. Representatives visited him offering generous research grants and institutional support. All he had to do was redirect his focus elsewhere.

Patterson refused.

So they tried to destroy him professionally.

His funding from petroleum-connected sources was immediately cut. The industry pressured his university to dismiss him. They used their influence to block his papers from peer-reviewed journals. They publicly dismissed him as an overzealous geologist stepping outside his expertise.

For years, it worked. Patterson was marginalized, labeled an alarmist, and isolated from mainstream scientific discussions.

But Patterson had something the industry couldn’t counter: evidence from before the contamination began.

He realized he needed a time machine—a way to prove what Earth’s atmosphere was like before automobiles. So he traveled to one of the most remote places on the planet: Greenland.

In brutal, freezing conditions, Patterson and his team drilled deep into ancient glaciers, extracting long cylinders of ice. These ice cores were frozen time capsules. Snow that fell in 1700 was preserved deep in the ice. Snow from 1900 was higher up. Snow from the 1950s was near the surface.

Back in his clean lab, Patterson carefully melted layers of ice from different time periods and measured their lead content.

The results were devastating to the industry’s claims.

For thousands of years, atmospheric lead levels were essentially zero. Then, starting precisely in the 1920s—exactly when leaded gasoline was introduced—the levels shot upward like a rocket. The graph was unmistakable. The contamination wasn’t natural. It was recent, man-made, and accelerating.

Armed with this irrefutable proof, Patterson returned to the fight.

He testified before congressional committees, sitting across from industry lawyers who tried to confuse the science. He wasn’t comfortable with public speaking.

He was nervous, awkward, and preferred the quiet predictability of his laboratory. But he refused to back down.

He told legislators they were poisoning their own children. He showed them the ice core data. He made the invisible visible.

Slowly, reluctantly, the truth broke through.

Other scientists began supporting his findings. Public health advocates took notice. Parents started demanding action. The tide turned.

In the 1970s, the United States passed the Clean Air Act and began the slow process of removing lead from gasoline. It took years of regulatory battles, but eventually, unleaded gasoline became the standard.

The results were nothing short of miraculous.

Within years, blood lead levels in American children dropped by nearly 80%. An entire generation was saved from cognitive impairment, behavioral disorders, and reduced intelligence. Millions of lives were protected from lead-related health problems.

Clair Patterson had won.

Yet when he died in 1995, few outside the scientific community knew his name. He never received a Nobel Prize. He never became wealthy. He simply returned to his laboratory and continued studying the chemistry of the oceans and the history of the Earth.

Patterson’s story is a reminder of what integrity looks like when nobody’s watching.

It’s easy to do the right thing when the crowd is cheering. It’s infinitely harder when powerful interests are trying to ruin you, when your career is threatened, when taking the money would be so much easier.

He could have stayed silent. He could have enjoyed a comfortable, well-funded career studying rocks while children’s minds were damaged. He could have said, “Not my problem.”

But he looked at the data, looked at the world, and decided truth mattered more than comfort.

He gave us the age of the Earth—a number that changed our understanding of time itself.

And then he gave us a future—a world where children could grow up without poison in their lungs.

We often imagine heroes as soldiers, activists, or celebrities. But sometimes a hero is just a stubborn man in a white lab coat, scrubbing a floor over and over, refusing to accept a convenient lie.

He cleaned the room.

And then he cleaned the world.