I was locking the door on fifty years of my life when he slammed his hand against the glass, desperate, looking like a man who was about to lose the only thing keeping him tethered to the earth.

I didn’t want to open it. The “For Lease” sign was already taped up, mocking me with its bright orange optimism. Inside, my shop was dark. The air smelled of what it always had: ozone, solder, and dust that settled before the internet was born. I was done. At seventy-four, my back felt like a rusted hinge and my rent had just tripled because the neighborhood now needed another artisanal cold-brew coffee lab more than it needed a man who could rewire a lamp.

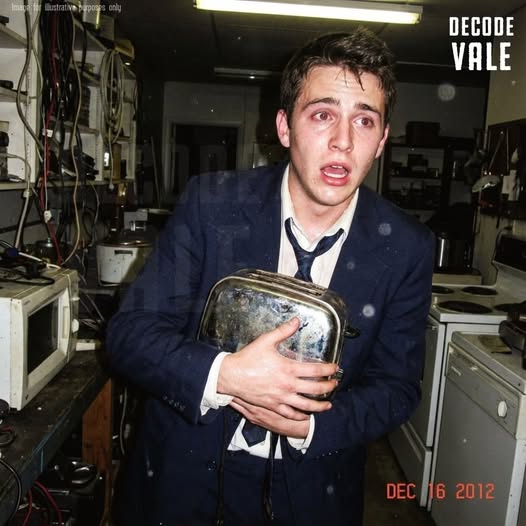

But the boy—he couldn’t have been more than twenty-eight—kept pounding. He wasn’t threatening; he was terrifyingly fragile. He held a cardboard box against his chest like it contained a bomb or a beating heart.

I sighed, the sound rattling in my chest, and turned the key one last time.

“We’re closed,” I said, cracking the door. “Permanently. Read the sign.”

“Please,” he gasped. He was wearing a suit that cost more than my van, but his eyes were red-rimmed shadows. “You’re the only one left. I Googled ’repair shops’ for three hours. You’re the only one who doesn’t just sell phone cases.”

He pushed past me before I could argue, placing the box on the counter. He opened it with trembling hands. Inside wasn’t a bomb. It was a toaster.

Not one of those plastic shells you buy for twenty bucks at a big-box store that die in six months. This was a 1950s chrome tank. Heavy as a cinderblock, with rounded curves and a cloth-wrapped cord.

“It won’t go down,” he said, his voice cracking. “The lever. It won’t stay down.”

I looked at the clock. I had to be out by five. “Son, go buy a new one. That thing is a fire hazard.”

“I can’t,” he whispered. “It was my grandmother’s. She died Tuesday. The funeral is tomorrow morning. I promised my mom… I promised I’d make Gram’s cinnamon toast for breakfast before we leave for the cemetery. It’s the only thing that feels real right now. And I broke it.”

He looked up at me, and I saw the crack in his veneer. He wasn’t just talking about a kitchen appliance.

“I tried to fix it,” he confessed, looking at his hands—soft, uncalloused, typing hands. “I watched a video. But I couldn’t even find a screw. It’s like a puzzle I’m too stupid to solve. Everything I own is like that. I pay for it, but I don’t understand it.”

That hit me. That was the sickness of this whole decade.

I locked the door and flipped the sign to Closed. “Bring it here.”

I cleared a space on the workbench, sweeping aside the remnants of my packing. I plugged in my soldering iron. It hummed to life, a familiar comfort.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Julian.”

“I’m Elias. Now, Julian, look at this.” I pointed to the bottom of the toaster. “You couldn’t find the screws because they didn’t want you to. But back when this was made, they assumed the owner had a brain. The tabs are hidden under the rubber feet.”

I popped the feet off and unscrewed the base. The chrome shell slid off, revealing the naked machinery inside. It was beautiful in its simplicity. Mica sheets, nichrome wire, a simple bimetallic strip. No microchips. No software updates. No terms of service.

“You’re an engineer?” I asked, noticing the ring on his finger—the iron ring of the profession.

Julian laughed, a bitter, dry sound. “Software. I work for a… a large platform. You know what I did last week? I spent sixty hours optimizing an algorithm that keeps teenagers staring at their screens three seconds longer. That’s my contribution to history. If I died today, my work would be deleted or rewritten in a month.”

He stared at the exposed wires of the toaster. “This thing… this thing has lasted seventy years. It fed my dad. It fed me. What have I built that will last seventy years?”

I handed him a pair of needle-nose pliers. “Stop talking. Hold this spring.”

He hesitated. “I might break it.”

“It’s already broken,” I grunted. “That’s the beauty of metal, Julian. It forgives you. You bend it back. You try again. It’s not like your code. You can touch it.”

I guided his hands. We found the problem—a buildup of carbon on the electromagnet contact and a bent latch arm.

“This is why I’m closing,” I said, scraping the carbon away with a small file. “Nobody wants to scrape the carbon anymore. It’s cheaper to throw it in a landfill and buy a new shiny box. They call it ’convenience.’ I call it surrendering.”

“It’s not just convenience,” Julian said softly. “It’s exhaustion, Elias. We’re tired. I make six figures, and I can’t afford a house in this zip code. I have a degree, and I’m terrified of an AI taking my desk. Everything feels like a subscription. I rent my music, I rent my storage, I rent my life. This toaster… it’s the only thing I actually have.”

I looked at him. Really looked at him. I saw the anxiety that seemed to vibrate in the air around young people these days. They were told they could be anything, but they ended up being users. Customers. Data points.

“Then earn it,” I said sternly. “Tighten that nut. Not too hard—snug. Feel the tension.”

He turned the screwdriver. He bit his lip. For twenty minutes, the world outside didn’t exist. There were no emails, no shareholders, no rent hikes. Just the mechanical logic of a latch engaging with a catch. Cause and effect. Tangible truth.

“Okay,” I said. “Plug it in.”

He hesitated, then pushed the plug into the wall. He pressed the lever down.

Click.

It stayed.

We waited. Ten seconds. Twenty. Then, the faint, dry scent of heating dust filled the shop—the perfume of resurrection. The coils inside glowed a deep, angry orange. It was alive.

Julian let out a breath that sounded like a sob. He stared into the glowing coils as if they were a campfire in a frozen wilderness.

“We did it,” he whispered.

“You did it,” I corrected. “I just showed you where to look.”

He pulled a wallet from his jacket. It was thick, expensive leather. “How much? I’ll write you a check. Five hundred? A thousand? Seriously, name it.”

I unplugged the iron and started winding the cord. “Put your money away.”

“No, I have to pay you. You saved me.”

“You can’t pay me, son. The business is closed. Remember?” I picked up the screwdriver we’d used—an old Craftsman with a clear acetate handle, battered and stained with grease from 1985. I pressed it into his hand.

“Take this.”

“What? No, I can’t—”

“Take it,” I commanded. “This is the payment. Listen to me. The world you’re living in? It wants you to be helpless. It wants you to throw things away so you have to buy them again. It wants you to feel like you can’t impact your own reality.”

I closed his fingers around the handle.

“When you go home, don’t just make toast. Look around your apartment. Find a loose hinge. Tighten it. Find a wobbly chair. Glue it. Reclaim your hands, Julian. If you can fix a toaster, you can fix other things. Maybe even things that aren’t made of metal.”

He looked at the tool, then at me. The panic was gone from his eyes, replaced by a quiet, steady weight. He nodded.

He packed the warm toaster back into the box with a reverence usually reserved for religious artifacts. He shook my hand—a firm grip, stronger than when he walked in.

“Thank you, Elias.”

“Go make that toast,” I said.

I watched him walk out. He didn’t check his phone. He walked differently, with the stride of a man who knew how the world worked under the hood.

I turned off the lights in the shop. I looked at the empty shelves, the dusty floor. I wasn’t sad anymore. They could tear this building down. They could put up another glass tower filled with people renting their lives one month at a time. But they couldn’t take away what just happened.

We are told that we are consumers. That we are helpless against the tide of the economy, of technology, of time. But that is a lie sold to us to keep us buying.

The truth is simpler, and it’s the only thing worth knowing:

Anything can be fixed, as long as there is a hand willing to hold the tool, and a heart patient enough to understand why it broke.

I locked the door, leaving the key in the mailbox. I didn’t need it anymore. I had done my job. The shop was closed, but the work—the real work—would continue in a kitchen somewhere, over the smell of cinnamon and heat, where a young man was learning that he wasn’t broken, just in need of a little repair.