June 6, 1944.

As the landing craft approached Utah Beach, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. gripped his cane and checked his pistol.

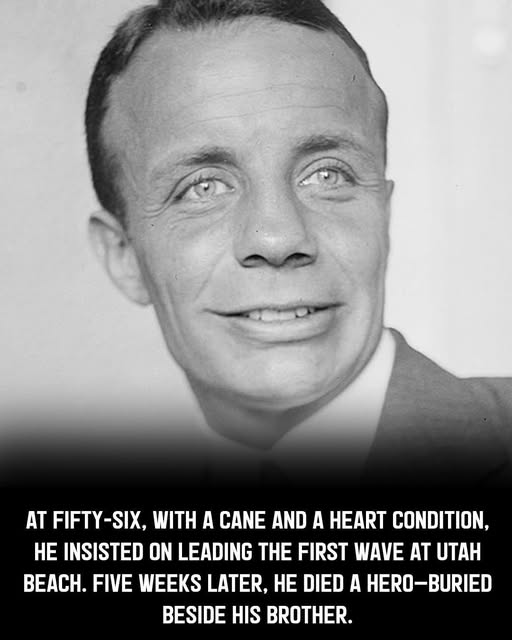

He was fifty-six years old. His heart was failing. Arthritis had crippled his joints from old World War I wounds. Every step hurt.

He wasn’t supposed to be there.

But he had insisted—three times—on going ashore with the first wave of troops. His commanding officer, Major General Raymond “Tubby” Barton, had rejected the request twice. Too dangerous. Too risky. No place for a general.

Roosevelt wrote a letter. Seven bullet points. The last one: “I personally know both officers and men of these advance units and believe that it will steady them to know that I am with them.”

Barton relented.

And so Theodore Roosevelt Jr.—eldest son of President Theodore Roosevelt, veteran of World War I, twice wounded, gassed nearly to blindness—became the only general officer to storm the beaches of Normandy in the first wave.

This wasn’t ancient history. This was June 6, 1944.

The ramp dropped. German guns opened fire. Bullets slapped the water. Artillery shells screamed overhead. Men scrambled onto the sand, some falling before they took three steps.

Roosevelt stepped off the boat, leaning on his cane, carrying only a .45 caliber pistol.

One of his men later recalled: “General Theodore Roosevelt was standing there waving his cane and giving out instructions as only he could do. If we were afraid of the enemy, we were more afraid of him and could not have stopped on the beach had we wanted to.”

Within minutes, Roosevelt realized something was wrong.

The strong tidal currents had pushed the landing craft off course. They’d landed nearly a mile south of their target. The wrong beach. The wrong exits. The whole invasion plan suddenly useless.

Men looked around in confusion. Officers checked maps. The Germans kept firing.

This was the moment that could turn the invasion into a massacre.

Roosevelt calmly surveyed the shoreline. Studied the terrain. Made a decision.

Then he gave one of the most famous orders in D-Day history:

“We’ll start the war from right here!”

For the next four hours, Theodore Roosevelt Jr. stood on that beach under relentless enemy fire, reorganizing units as they came ashore, directing tanks, pointing regiments toward their new objectives. His cane tapping in the sand. His voice steady. His presence unshakable.

A mortar shell landed near him. He looked annoyed. Brushed the sand off his uniform. Kept moving.

Another soldier described seeing him “with a cane in one hand, a map in the other, walking around as if he was looking over some real estate.”

He limped back and forth to the landing craft—back and forth, back and forth—personally greeting each arriving unit, making sure the men kept moving off the beach and inland. The Germans couldn’t figure out what this limping officer with the cane was doing. Neither could they hit him.

By nightfall, Utah Beach was secure. Of the five D-Day landing beaches, Utah had the fewest casualties—fewer than 200 dead compared to over 2,000 at Omaha Beach just miles away.

Commanders credited Roosevelt’s leadership under fire for the success.

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. had been preparing for that day his entire life.

Born September 13, 1887, at the family estate in Oyster Bay, New York, he was the eldest son of Theodore Roosevelt—the larger-than-life president, war hero, and force of nature. Growing up in that shadow was impossible. Meeting that standard seemed even harder.

But Ted tried.

In World War I, he’d been among the first American soldiers to reach France. He fought at the Battle of Cantigny. Got gassed. Got shot. Led his men with such dedication that he bought every soldier in his battalion new combat boots with his own money. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Then, in July 1918, his youngest brother Quentin—a pilot—was shot down and killed over France.

Ted never fully recovered from that loss.

When World War II began, Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was in his fifties. Broken down. Worn out. He could have stayed home. Taken a desk job. No one would have blamed him.

Instead, he fought his way back into combat command. He led troops in North Africa. Sicily. Italy. Four amphibious assaults before Normandy.

And on D-Day, when commanders tried to keep him off that beach, he refused.

“The first men to hit the beach should see the general right there with them.”

After Utah Beach, General Omar Bradley—who commanded all American ground forces in Normandy—called Roosevelt’s actions “the bravest thing I ever saw.”

General George Patton agreed. Days later, Patton wrote to his wife: “He was one of the bravest men I ever knew.”

On July 11, 1944—thirty-six days after D-Day—General Eisenhower approved Roosevelt’s promotion to major general and gave him command of the 90th Infantry Division.

Roosevelt never got the news.

That same day, he spent hours talking with his son, Captain Quentin Roosevelt II, who had also landed at Normandy on D-Day—the only father-son pair to come ashore together on June 6, 1944.

Around 10:00 p.m., Roosevelt was stricken with chest pains.

Medical help arrived. But his heart had taken all it could take.

At midnight on July 12, 1944—five weeks after leading men onto Utah Beach—Theodore Roosevelt Jr. died in his sleep.

He was fifty-six years old.

Generals Bradley, Patton, and Barton served as honorary pallbearers. Roosevelt was initially buried at Sainte-Mère-Église.

In September 1944, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. When President Roosevelt handed the medal to Ted’s widow, Eleanor, he said, “His father would have been proudest.”

After the war, Roosevelt’s body was moved to the Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer—the rows of white crosses overlooking Omaha Beach.

And there’s where the story takes its final, heartbreaking turn.

In 1955, the family made a request: Could Quentin Roosevelt—Ted’s younger brother, killed in World War I, buried in France since 1918—be moved to rest beside his brother?

Permission was granted.

Quentin’s remains were exhumed from Chamery, where he’d been buried near the spot his plane crashed thirty-seven years earlier, and reinterred beside Ted.

Two sons of a president. Two brothers. Two wars. Reunited in foreign soil.

Quentin remains the only World War I soldier buried in that World War II cemetery.

Today, at the Normandy American Cemetery, among the 9,388 white marble crosses and Stars of David, two headstones stand side by side:

THEODORE ROOSEVELT JR.

BRIGADIER GENERAL

MEDAL OF HONOR

QUENTIN ROOSEVELT

SECOND LIEUTENANT

WORLD WAR I

The tide still rolls over Utah Beach. The sand looks the same. Tourists walk where soldiers died.

And somewhere in that vast field of white crosses, two brothers rest together—sons of a president who believed in duty, service, and leading from the front.

Some men lead by orders.

Some lead by rank.

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. led by example—cane in hand, heart failing, utterly unflinching.

He didn’t have to be there.

But he refused to lead from anywhere else.