In 1970, a 23-year-old physics student at Imperial College London was deep into his doctoral research on cosmic dust when he faced an impossible choice.

Brian May had spent three years studying the zodiacal dust cloud—the faint glow of sunlight reflecting off tiny particles scattered throughout the solar system. He’d built his own equipment, collected data, analyzed measurements, and was making genuine progress toward his PhD in astrophysics.

But he was also the guitarist for a rock band that was starting to gain serious attention.

The band was called Queen. They’d just signed a record deal. Tours were being planned. The opportunity was real, immediate, and unlikely to wait while May finished his academic work.

Standing at that crossroads, May made a decision that would leave a question unanswered for 36 years: he chose the guitar over the telescope.

Queen’s rise was meteoric. By the mid-1970s, they were one of the biggest bands in the world. “Boheman Rhapsody” became one of rock’s most iconic songs. May’s guitar work—his distinctive tone created using a homemade guitar called the Red Special—became instantly recognizable. Albums sold millions. Stadiums filled with fans singing along to “We Will Rock You” and “We Are the Champions.”

May’s academic work sat unfinished, his thesis incomplete, his research abandoned but never quite forgotten.

For most people, that would have been the end of the story. A promising academic career sacrificed for rock stardom—a trade-off that millions would gladly make. The PhD simply wasn’t meant to be.

But Brian May wasn’t most people.

Even as Queen dominated the rock world throughout the 1970s and 80s, May maintained his interest in astronomy and astrophysics. He read scientific journals. He attended lectures when touring schedules allowed. He stayed connected to the academic world he’d left behind, following developments in his field, watching as technology advanced and understanding of the solar system deepened.

His thesis supervisor, Professor Michael Rowan-Robinson, had told him decades earlier: “You can always come back and finish.”

May had never forgotten those words.

In 2006, more than three decades after walking away from Imperial College to tour with Queen, Brian May decided it was time.

He contacted Professor Rowan-Robinson, who was still at Imperial College and still remembered his former student who’d left to become a rock star. They discussed whether it was feasible to complete the work May had started in 1970.

The challenge was significant. Astrophysics had advanced enormously in 36 years. The technology May had used for his original observations was obsolete. The data he’d collected was valuable but incomplete by modern standards. Simply picking up where he left off wouldn’t work—he’d need to update his research, incorporate decades of new discoveries, and meet current academic standards.

But the core of his original work remained valid. His observations of the zodiacal dust cloud were still relevant. His research questions were still meaningful. And Rowan-Robinson was willing to supervise him to completion.

May threw himself into the work with the same intensity he’d brought to Queen’s music.

While still maintaining his music career—performing with Queen + Paul Rodgers and working on various projects—May carved out time to update his thesis. He revisited his original data from the early 1970s. He studied the decades of subsequent research on zodiacal dust. He incorporated modern measurements and refined his analysis using contemporary techniques.

The thesis he ultimately submitted was titled “A Survey of Radial Velocities in the Zodiacal Dust Cloud.” It examined the motion of dust particles in the plane of the solar system, work that contributed to understanding how dust behaves in space—research relevant to everything from asteroid studies to the formation of planetary systems.

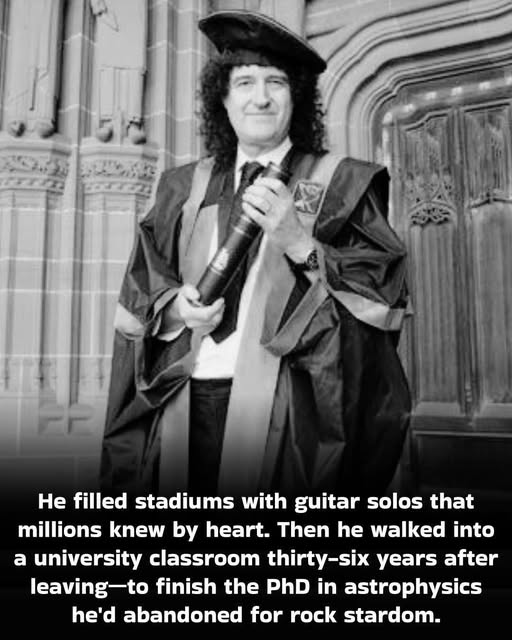

In August 2007, Imperial College London awarded Brian May a PhD in astrophysics.

Not an honorary degree—universities frequently give those to celebrities and donors without requiring actual academic work. This was a real PhD, earned through genuine research, peer review, and the same rigorous standards applied to any doctoral candidate.

The examination was conducted by experts in the field who evaluated his work on its scientific merits, not his fame as a guitarist. The thesis had to withstand the same scrutiny any astrophysics PhD would face. May had to defend his research, answer technical questions, and demonstrate mastery of his subject.

He passed.

At age 60, Brian May—rock legend, guitarist whose solos had been heard by hundreds of millions—became Dr. Brian May, astrophysicist.

The accomplishment made headlines around the world, but not because a celebrity had purchased a credential or received an honorary title. It made news because it was genuinely remarkable: a world-famous musician had returned to complete legitimate academic work abandoned 36 years earlier, proving that it’s never too late to finish what you started.

The story resonated because it defied easy categorization. We’re used to dividing people into categories: artists versus scientists, creative types versus analytical minds, rock stars versus academics. Brian May refused to fit into any single box.

He’d always been both.

As a child, May had been fascinated by the night sky. He built telescopes with his father. He studied physics and mathematics not because he had to, but because he loved understanding how the universe worked. When he got to Imperial College—one of the world’s top science universities—he excelled academically while also playing guitar in bands.

The guitar he played, the legendary Red Special, was itself a fusion of science and art. May and his father had built it by hand when Brian was a teenager, using materials including parts of an old fireplace mantle, motorcycle springs, and knitting needles. Every design choice was carefully calculated for acoustic properties and tonal qualities. The result was an instrument with a unique sound that would become part of rock history.

That blend of scientific thinking and artistic creativity defined everything May did. His guitar solos were technically complex but emotionally powerful. His approach to music was both intuitive and analytical. He didn’t see science and art as opposites—to him, they were different expressions of the same curiosity about the world.

Earning the PhD wasn’t about proving anything to critics or adding credentials to his resume. May didn’t need the degree for career advancement—he was already one of the most successful musicians in history. He pursued it because the unfinished work bothered him, because he’d always wondered what conclusions his research would reach, because he valued knowledge for its own sake.

After earning his PhD, May didn’t treat it as a culmination but as a beginning. He became increasingly active in science advocacy and public education about astronomy. He served as Chancellor of Liverpool John Moores University for over a decade. He co-founded Asteroid Day, an annual event raising awareness about asteroid impacts. He collaborated with NASA on various projects, including creating stereoscopic images from the New Horizons mission to Pluto.

He published books combining his interests, including academic books about stereoscopy and popular books about astronomy illustrated with historic 3D photographs. He gave lectures at universities worldwide, speaking about both his astrophysics research and the intersection of science and creativity.

And he continued making music, because he never had to choose between being a scientist and being an artist—he was always both.

The 36-year gap in his academic career became part of his story, not a failure but proof that paths don’t have to be linear. You can start something, set it aside for a valid reason, and come back to it decades later if it still matters to you.

That message resonated far beyond the worlds of rock music and astrophysics. Students who’d left school to work could see that returning was possible. People who’d abandoned dreams for practical reasons found encouragement. Anyone who’d ever felt they had to choose between two passions saw an example of someone who ultimately refused to choose.

When May received his doctorate, he joked in interviews that his thesis was “the world’s longest delayed homework assignment.” But beneath the humor was a serious point: intellectual curiosity doesn’t expire. Knowledge you once pursued remains valuable even if you step away from it. And completing something you started, even decades later, brings its own satisfaction independent of external recognition.

The story of Dr. Brian May, astrophysicist and rock legend, stands as a reminder that human beings are not meant to fit into single categories. We can contain multitudes. We can excel in completely different domains. We can be both the person shredding guitar solos in front of 80,000 fans and the person quietly analyzing data about cosmic dust.

In fact, the same qualities that made May an exceptional musician—attention to detail, pattern recognition, creative problem-solving, dedication to craft—translated directly to his scientific work. The disciplines weren’t as separate as they seemed.

Today, when astrophysicists discuss zodiacal dust or musicians analyze Brian May’s guitar technique, they’re talking about the same person—someone who proved that you don’t have to choose between passion and profession, between art and science, between finishing what you started and embracing new opportunities.

You can have both. It might just take 36 years.

But as Dr. Brian May demonstrated: some things are worth coming back to finish, no matter how long the journey takes.