All four engines died at 37,000 feet—and the captain’s announcement became the calmest statement in aviation history.

June 24, 1982. Seven miles above the Indian Ocean.

British Airways Flight 9—a Boeing 747 carrying 263 souls—was cruising peacefully through the night when something impossible began.

First, the crew noticed St. Elmo’s fire. An eerie blue glow crackling across the cockpit windows like electricity dancing on glass.

Then shimmering sparks appeared along the wings, as if the aircraft were trailing fire through darkness.

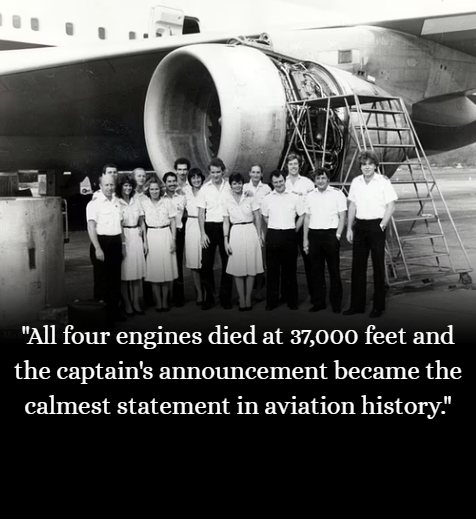

Captain Eric Moody and his crew had thousands of flying hours between them. They’d seen unusual weather. They’d handled emergencies.

But they’d never seen anything like this.

Then came the alarm they dreaded most.

Engine four had failed.

Before they could process it, engine two quit.

Then engine one.

Then engine three.

In less than 90 seconds, all four engines had stopped.

Complete silence.

At seven miles above the ocean.

A commercial jet losing one engine is manageable. Losing two is a serious emergency. Losing three is catastrophic.

Losing all four?

That’s not supposed to happen. Ever.

Yet here was Captain Moody, flying a 300-ton glider with 263 people aboard, no engines, no power, and no idea why.

The 747 was descending—losing altitude at an alarming rate. Below them: the dark Indian Ocean and the mountainous Indonesian coastline.

They had minutes to figure out what happened and somehow restart the engines.

In the cabin, passengers saw strange sparks outside their windows. Oxygen masks dropped. Thick, acrid smoke filled the air, smelling like sulfur.

People began writing farewell notes.

Then Captain Moody’s voice came over the intercom with what would become one of the most famous announcements in aviation history:

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain speaking. We have a small problem. All four engines have stopped. We are doing our damnedest to get them going again. I trust you are not in too much distress.”

A small problem.

All four engines stopped.

Seven miles in the sky.

That’s not just British understatement. That’s leadership—keeping 263 people calm while facing catastrophe.

In the cockpit: controlled chaos.

Senior First Officer Roger Greaves’ oxygen mask had broken, leaving him gasping in the thin air. Moody immediately descended—trading precious altitude for breathable air.

Flight Engineer Barry Townley-Freeman worked frantically through engine restart procedures while First Officer Barry Fremantle handled communications with Jakarta.

They tried restarting the engines.

Nothing.

Again. Nothing.

Ten attempts. Twelve. Fifteen.

Each failure meant less altitude. Less time. Less sky.

The aircraft descended through 15,000 feet. Then 14,000. Then 13,000.

Below them, somewhere in darkness, were Java’s mountains.

They were running out of options.

At 13,500 feet—with terrain looming—engine four suddenly coughed, sputtered, and roared back to life.

Then engine three.

Then engine one.

Finally, engine two.

All four engines—dead for 13 minutes and 13,000 feet of descent—had somehow restarted.

They had power. They had control.

But they still weren’t safe.

Whatever had killed the engines had also destroyed the windscreen. The windows were opaque, sandblasted to translucence by millions of tiny particles traveling at 500 mph.

Captain Moody could barely see through them.

They had to land this crippled aircraft essentially flying blind.

They used side windows for glimpses. Relied on instruments. Followed radio guidance from Jakarta, trusting voices from the ground.

And somehow, impossibly, Captain Moody brought the battered 747 down safely at Jakarta’s Halim Perdanakusuma Airport.

Not a single person died.

All 263 passengers and crew walked away.

Only after landing did investigators discover the truth.

Mount Galunggung in Java had been erupting. On June 24, it sent a massive ash cloud eight miles high—spreading across flight paths.

Flight 9 had flown directly through it in darkness.

Volcanic ash is pulverized rock—microscopic glass shards suspended in air. Invisible to weather radar. Nearly impossible to see at night.

When jet engines running at over 1,000 degrees ingest it, the ash melts instantly, coating components like molten glass and choking the engines completely.

The engines restarted only because Moody’s descent brought them below the ash cloud, where cooler air allowed the melted glass to solidify and break off.

It was luck as much as skill.

But the skill kept them alive long enough for the luck to matter.

British Airways Flight 9 changed aviation forever.

Before June 24, 1982, volcanic ash was considered a minor nuisance.

After Flight 9:

Global volcanic ash detection systems were established

Airlines receive real-time eruption alerts.

Flight paths are immediately rerouted around ash clouds

The International Airways Volcano Watch was created.

Captain Moody’s experience—and his crew’s quick thinking—saved not just 263 people that night.

It potentially saved thousands in the decades since.

Captain Moody continued flying until retirement. He’s remembered not just for his skill, but for that famous announcement—the calm understatement quoted in aviation training worldwide.

“We have a small problem. All four engines have stopped.”

That’s leadership. Keeping people calm when the world is falling apart. Refusing to give up when giving up would be understandable.

The lesson:

The impossible sometimes happens. Prepare anyway.

Calm leadership saves lives. Panic kills.

Never give up. Moody’s crew tried over 15 times to restart those engines. The 15th attempt worked. If they’d stopped at 14, everyone dies.

June 24, 1982.

All four engines died at 37,000 feet.

The crew had 13 minutes to solve an impossible problem.

They couldn’t see why the engines failed.

They couldn’t see the ash cloud killing them.

They couldn’t see the runway when they landed.

But they could think. They could try. They could refuse to quit.

And 263 people survived because four men in a cockpit refused to accept the impossible.

That’s not just an aviation story.

That’s a reminder that even when all four engines fail—literally and metaphorically—you keep trying. You stay calm. You don’t give up.

Because sometimes, the 15th attempt is the one that works.