Richard Feynman opened a sealed safe at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project using nothing but memory, intuition, and a borrowed screwdriver, then calmly handed out classified files to startled physicists to prove that the world’s most secure laboratory was not secure at all.

He was supposed to focus on equations that would change history, yet he could not ignore the simple fact that the military treated secrecy like magic instead of engineering.

Feynman overheard officers bragging about unbreakable locks. He asked for a copy of the combination system. No one gave it to him, so he studied the filing cabinets instead. He noticed scratches near common numbers, patterns in how physicists set combinations, and the lazy habit of choosing birthdays. Within weeks he opened dozens of safes across the lab with nothing but logic.

He never stole anything. He left polite notes that read, “Please improve your security.” Some generals were furious. Others were terrified. Feynman kept telling them that the point of science was honesty, not ceremony.

Los Alamos changed him. He arrived grieving the death of his first wife, Arline. He wrote her letters every day even after she passed, placing them in a box he kept hidden in his dorm room. He played bongos at night to stay sane. He solved problems on cafeteria napkins. He asked questions that made senior physicists pause. Why does this assumption exist? How do we know it is true? Have we tested it?

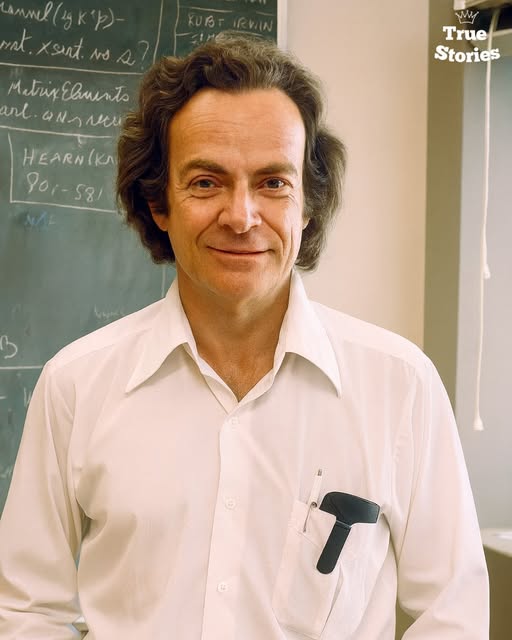

He carried that mindset into the world after the war. At Cornell he lectured with a style students described as electricity. His chalk moved faster than most people could think. Then came Caltech, where he wrote on every surface he could find, including plates, windows, and the back of menus. He once explained quantum electrodynamics on a diner napkin so clearly that the waitress asked if he could tutor her son.

His greatest public moment came in 1986. The Space Shuttle Challenger had exploded and the Rogers Commission asked for his help. Feynman sat through days of technical explanations. Then he dipped a small piece of rubber O ring into a glass of ice water on live television. The rubber stiffened instantly. The room fell silent. Feynman looked up and said, “This is how it happened.” No politics. No spin. Just truth made visible.

He won the Nobel Prize, yet he preferred talking with undergraduates. He hated prestige. He loved curiosity. He believed nature was endlessly interesting if you looked closely enough.

Richard Feynman lived by a simple rule.

If something mattered, he tested it for himself, and he showed the world that clarity can be louder than power.