Summary:

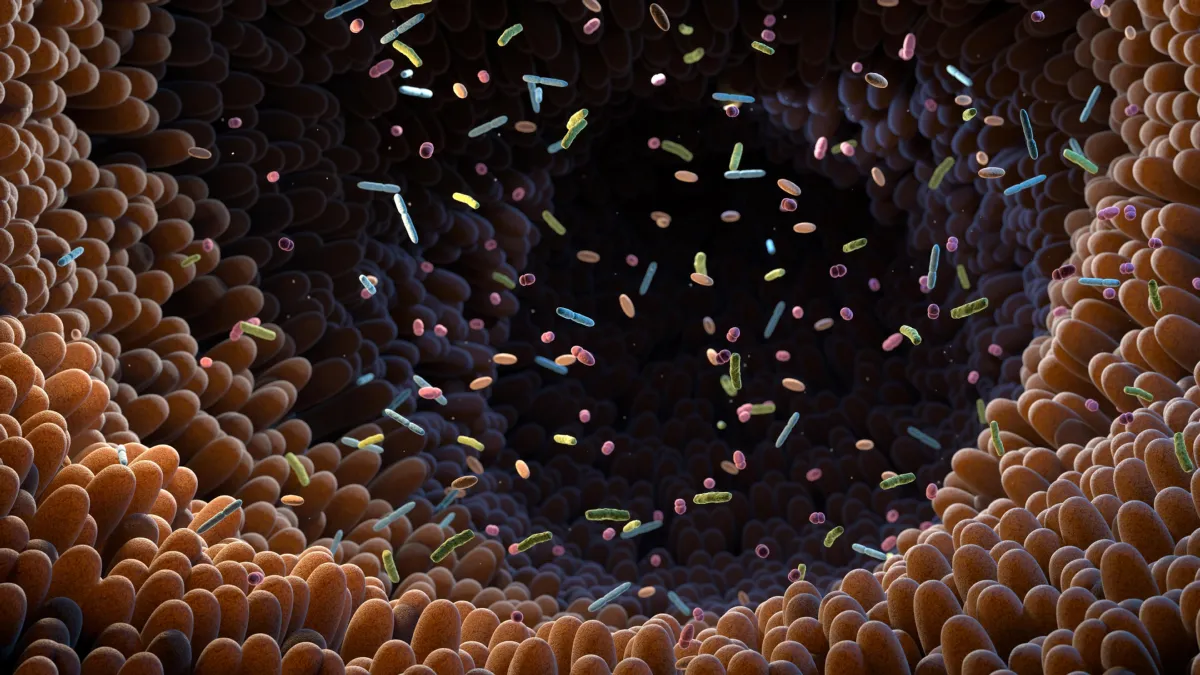

A global study has uncovered a mysterious group of gut bacteria that shows up again and again in healthy people. Known as CAG-170, these microbes were found at lower levels in people with a range of chronic diseases. Genetic clues suggest they help digest food and support the broader gut ecosystem. Researchers say the discovery could reshape how we measure and maintain gut health.

FULL STORY

Scientists have identified a hidden group of gut bacteria that appears to be strongly linked to good health worldwide. The discovery could help define what a healthy microbiome looks like and lead to more targeted probiotics in the future.

A large international study led by researchers at the University of Cambridge has identified a little-known group of gut bacteria that appears far more often in healthy people. The group, called CAG-170, was consistently found at higher levels in individuals without chronic illness.

CAG-170 is known only through its genetic signature. Scientists have not been able to grow most of these bacteria in the lab, which has made them difficult to study directly.

Using advanced computational techniques, the team searched for CAG-170’s genetic fingerprint in gut microbiome samples from more than 11,000 people across 39 countries. The pattern was clear. Healthy individuals had more of these bacteria than people with conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Further genetic analysis showed that CAG-170 has the ability to produce large amounts of Vitamin B12. It also carries enzymes that help break down carbohydrates, sugars, and fibers in the gut.

Researchers believe the Vitamin B12 produced by CAG-170 likely supports other beneficial gut bacteria rather than directly benefiting the person hosting it. In other words, these microbes may help maintain balance within the broader gut ecosystem.

The findings suggest that CAG-170 could eventually serve as a marker of gut microbiome health. They also point toward the possibility of developing probiotics designed specifically to maintain healthy levels of CAG-170.

Dr. Alexandre Almeida, a researcher in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Veterinary Medicine who led the study, said: “Our work has revealed that CAG-170 bacteria — part of the ‘hidden microbiome’ — appear to be key players in human health, likely by helping us to digest the main components of our food and keeping the whole microbiome running smoothly.”

He added: “We looked at the gut microbes of thousands of people across 39 countries and 13 different diseases including Crohn’s and obesity. We consistently found that people with these diseases had lower levels of CAG-170 bacteria in their gut.”

The study was published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

Exploring the ‘Hidden Microbiome’

This research builds on Almeida’s earlier effort to assemble a detailed reference library of microbial genomes found in the human gut. That resource, known as the ‘Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome catalogue’, maps the genetic blueprints of microbes that live inside us.

To create the catalogue, Almeida used a technique called ‘metagenomics’, which involves analyzing all microbial DNA in a gut sample at once and then separating it into individual species.

The work identified more than 4,600 bacterial species living in the gut. Remarkably, more than 3,000 of these had never been documented there before, highlighting how much of the microbiome remains unexplored.

The catalogue provides reference genomes for each species, including CAG-170. These references act like genetic fingerprints that allow researchers to detect specific microbes in other gut samples.

“Our earlier work revealed that around two-thirds of the species in our gut microbiome were previously unknown. No-one knew what they were doing there — and now we’ve found that some of these are a fundamental and underappreciated component of human health,” said Almeida.

Three Independent Analyses Confirm the Link

The team analyzed more than 11,000 gut microbiome samples from people living primarily in Europe, North America, and Asia. The dataset included healthy individuals as well as people diagnosed with 13 different diseases, including Crohn’s disease, colorectal cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis.

By comparing each sample to the Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome catalogue, researchers found that CAG-170 stood out as the group within the ‘hidden microbiome’ most strongly associated with good health. This pattern was consistent across countries.

In a second analysis, the scientists examined the full gut microbiome composition of more than 6,000 healthy individuals to identify which species appeared most capable of stabilizing the gut ecosystem. Once again, CAG-170 ranked as the group most consistently linked to health.

A third analysis focused on people with dysbiosis, a condition in which the gut microbiome becomes imbalanced. Lower levels of CAG-170 were associated with a greater likelihood of dysbiosis. This imbalance has been linked to long-term conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and anxiety and depression.

Implications for Future Probiotics

The human gut contains billions of bacteria representing about 4,600 species. Although each person’s microbial mix is unique, the overall goal of the microbiome is the same: to help the body function properly.

Researchers hope that by better defining what a healthy microbiome looks like, they can identify how it changes in disease and potentially restore balance. Tailored probiotics are one possible approach, and this study represents an important step in that direction.

“The probiotic industry hasn’t really kept up with gut microbiome research — people are still using the same probiotic species that were being used decades ago. We’re now discovering new groups of bacteria like CAG-170 with important links to our health, and probiotics aimed at supporting them could have a much greater health benefit,” said Almeida.

Until now, much of microbiome research has focused on bacteria that can be grown and studied in the lab. Most CAG-170 bacteria cannot yet be cultured this way. Scientists will need to develop new methods to grow and test them before these findings can lead to potential new therapies.

Journal Reference:

- Ana C. da Silva, Jacob Lapkin, Qi Yin, Efrat Muller, Alexandre Almeida. Meta-analysis of the uncultured gut microbiome across 11,115 global metagenomes reveals a candidate signature of health. Cell Host, 2026; DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2026.01.013