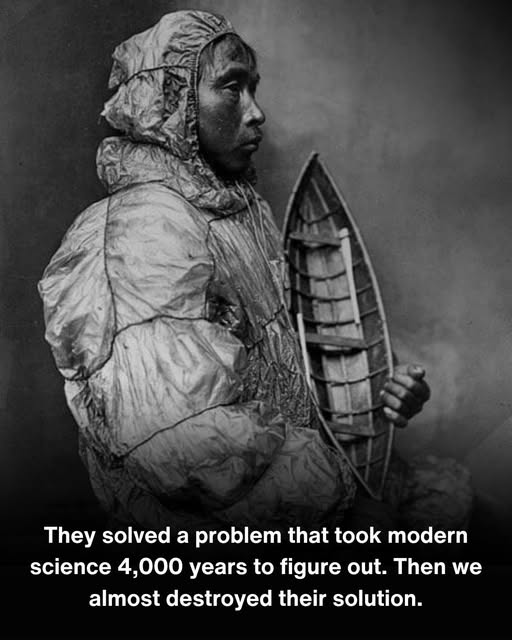

Picture the Arctic—where one clothing mistake means freezing to death in minutes. Where ocean spray at -40°F can kill you before you reach shore.

Indigenous Arctic peoples faced an impossible engineering challenge: create fabric that keeps freezing water OUT while letting body sweat ESCAPE. Because in the Arctic, trapped sweat is as deadly as seawater. Both cause hypothermia. Both kill.

Modern science “solved” this in 1969 when Bob Gore invented Gore-Tex—a revolutionary synthetic membrane with microscopic pores. Too small for water droplets to enter. Large enough for sweat vapor to escape. It changed outdoor clothing forever.

But here’s what they don’t teach you: Indigenous seamstresses had been wearing this exact technology for 4,000 years.

The Inupiat of Alaska. The Yupik of Siberia. The Inuit of Greenland. Across thousands of miles, they independently discovered the same solution: intestines.

Seal intestines. Walrus intestines. Whale intestines. Even bear intestines.

These weren’t crude survival tools. They were masterpieces of textile engineering.

Mammal intestines have a natural membrane structure that works like nature’s Gore-Tex. The outer surface is dense enough to block rain and ocean spray. The inner surface has microscopic pores that release water vapor from your sweat.

Water drops stay out. Sweat escapes. Perfect breathable waterproofing.

But the engineering brilliance wasn’t just the material—it was the construction.

Seamstresses (almost always women, deeply respected for their expertise) would harvest intestines from freshly killed animals. Clean them meticulously—any remaining tissue would rot the fabric. Wash them repeatedly in Arctic water. Then inflate them like translucent balloons and hang them to dry in subzero air.

When dried, intestines became thin, papery, remarkably strong material. A single intestine stretched 6-10 feet long.

Then came the real mastery: waterproof stitching.

Regular seams leak. So these women invented specialized techniques—overlapping strips precisely, using sinew thread, coating seams with seal oil. Each stitch tight enough to prevent leaks, flexible enough to allow movement.

A single parka used intestines from dozens of animals. Thousands of individual stitches. Months of work.

The result? Garments weighing just 85 grams—lighter than your smartphone—that could keep hunters dry through hours of Arctic storms and ocean spray.

They were translucent. Light glowed through them like frosted glass. Some seamstresses added dyed strips, creating patterns that transformed survival gear into wearable art.

For a kayak hunter, these parkas were as essential as the paddle itself. One wave over the bow with regular clothing meant death in minutes. The gut parka was the difference between life and drowning in icy water.

For 4,000 years, this knowledge passed from mother to daughter. Master seamstress to apprentice. The skills survived through practice, necessity, and the simple truth that your family’s survival depended on your ability to make clothing that worked.

Then the 20th century arrived.

Synthetic fabrics. Rubber raincoats. Nylon. Gore-Tex. Materials you could buy instead of make. Materials that didn’t require months of skilled labor.

Traditional gut parka production collapsed. First slowly. Then rapidly.

By the late 1900s, elders who remembered the techniques were dying. Young people learned Western methods instead. The waterproof seam techniques, the specific stitching patterns, the intestine preparation secrets—all nearly extinct.

Some techniques were lost forever.

But not all.

Today, Indigenous communities across the Arctic are fighting to revive this knowledge. Elders teaching younger generations. Museums documenting historical garments. Artists experimenting to reconstruct lost methods.

In 2022, a Sugpiaq elder in Cordova, Alaska, led artists in creating a bear gut parka—one of the first made in generations. They spent months relearning preparation techniques, problem-solving when modern needles didn’t work like traditional bone needles.

They succeeded. They recreated 4,000-year-old technology that still works perfectly today.

This isn’t just preserving history. This is recognizing that “primitive” peoples were brilliant engineers who understood breathable waterproofing principles thousands of years before our laboratories “discovered” them.

Modern outdoor companies spend millions developing waterproof-breathable fabrics. They patent molecular structures. They market “revolutionary” materials.

Every single principle was already understood and applied by Arctic seamstresses 4,000 years ago.

They didn’t have electron microscopes or chemical labs. They had observation, experimentation, and generations of accumulated wisdom. They tested materials, refined techniques, and created clothing that worked in Earth’s most extreme environment.

The intestine parkas prove something powerful: human ingenuity isn’t about technology level. It’s about solving problems with what you have. Observing nature’s solutions. Respecting the knowledge of those who came before.

4,000 years before Gore-Tex, Arctic peoples invented waterproof, breathable fabric.

They created garments lighter than modern rain jackets, more flexible than synthetic shells, perfectly adapted to their world.

Then Western culture called them primitive and almost erased their knowledge.

Now—finally—we’re beginning to understand what nearly vanished.

And across the Arctic, seamstresses are stitching those connections back together, one intestine at a time.