On the morning of April 29, 1975, Major Buang-Ly knew his country had hours left to live.

The South Vietnamese Air Force officer was stationed on Con Son Island, a small outpost fifty miles off the southern coast. The island served primarily as a prison camp, but it also had a small airfield—and on that airfield sat a two-seat Cessna O-1 Bird Dog, a light observation plane built for reconnaissance, not escape.

Buang-Ly looked at his wife. He looked at their five children, the youngest fourteen months old, the oldest just six. North Vietnamese forces were closing in. The prison guards were abandoning their posts. If they stayed, there would be no mercy for a military officer and his family.

He made his decision.

The Bird Dog was designed to carry a pilot and one observer. Buang-Ly helped his wife and all five children squeeze into the backseat and the small storage area behind it. He hot-wired the engine. As the tiny plane lifted off and banked toward the open sea, enemy ground fire zipped past them.

He had no radio. He had no destination. He had only the hope that somewhere out there, the American fleet was still operating.

For thirty minutes, Buang-Ly flew east over the South China Sea. Then he spotted them—helicopters, dozens of them, all flying in the same direction. He followed.

The helicopters led him to the USS Midway.

The aircraft carrier was in the middle of Operation Frequent Wind, the largest helicopter evacuation in American military history. More than seven thousand Americans and at-risk South Vietnamese were being airlifted from Saigon to the ships of Task Force 76. The Midway’s flight deck was chaos—helicopters landing, refugees pouring out, aircraft being pushed aside to make room for more.

At one point, the ship’s air boss counted twenty-six Huey helicopters circling the carrier, not one of them with working radio contact.

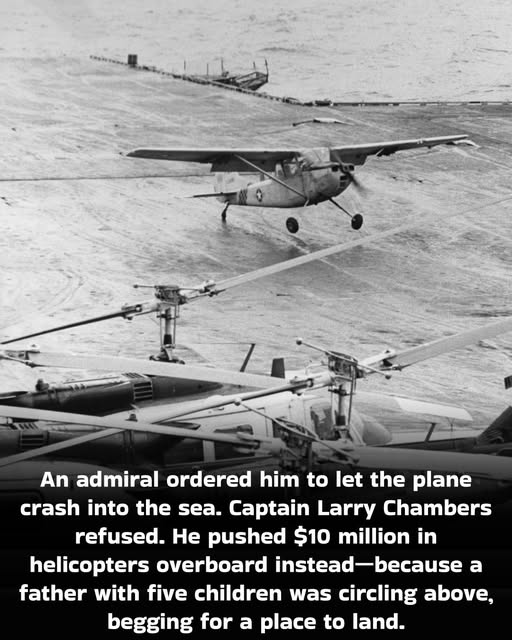

And then the spotters noticed something different. A fixed-wing aircraft. A tiny Cessna with South Vietnamese markings, circling overhead with its landing lights on.

Captain Lawrence Chambers had been in command of the Midway for barely five weeks. He was the first African American to command a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, a graduate of the Naval Academy who had risen through the ranks at a time when such advancement was far from guaranteed. Now he faced a decision that could end his career.

The admiral aboard the Midway told Chambers to order the pilot to ditch in the ocean. Rescue boats could pick up the survivors.

Chambers understood immediately why that wouldn’t work. The Bird Dog had fixed landing gear. The moment it hit the water, it would flip. With a plane packed full of small children, ditching meant drowning. The ship was a hundred nautical miles from the coast—too far for the Cessna to return even if there had been anywhere safe to land.

As the small plane continued circling, Buang-Ly tried to communicate the only way he could. He wrote a message on a scrap of paper and dropped it during a low pass over the deck.

The wind blew it into the sea.

He tried again. And again. Three notes disappeared into the water.

On the fourth attempt, desperate to make himself understood, Buang-Ly dropped a leather pistol holster with a message tucked inside. This time, a crewman grabbed it.

The note was scrawled on a navigational chart. The spelling was imperfect, the handwriting hurried, but the meaning was unmistakable:

“Can you move these helicopter to the other side, I can land on your runway, I can fly 1 hour more, we have enough time to move. Please rescue me. Major Buang, wife and 5 child.”

The message was rushed to the bridge. Chambers read it. He picked up the phone to call his air boss, Commander Vern Jumper.

“Vern,” he said, “give me a ready deck.”

Jumper’s response, Chambers later recalled, contained words he wouldn’t want to print.

It didn’t matter. Chambers called for volunteers—every available sailor, regardless of rank or duty, to the flight deck immediately. What followed was controlled pandemonium. Arresting wires were stripped from the deck—at the Bird Dog’s slow landing speed, they would trip the plane and send it cartwheeling. Helicopters that could be moved were shoved aside.

And the helicopters that couldn’t be moved quickly enough?

Chambers ordered them pushed over the side.

The sailors of the Midway shoved four UH-1 Huey helicopters and one CH-47 Chinook into the South China Sea. Ten million dollars worth of military hardware, tumbling into the waves. Chambers didn’t watch. He already knew the admiral was threatening to put him in jail.

“I was scared to death,” he admitted years later. But he also knew what would happen if he followed the order to let the plane ditch. “When a man has the courage to put his family in a plane and make a daring escape like that, you have to have the heart to let him in.”

Meanwhile, the ship’s chief engineer reported a problem. Half the Midway’s boilers had been taken offline for maintenance. They didn’t have enough steam to make the twenty-five knots Chambers needed to generate proper headwind for the landing.

Chambers told him to shift the hotel electrical load to the emergency diesel generators and make it happen.

The old carrier groaned as she picked up speed, turning into the wind. The ceiling was five hundred feet. Visibility dropped to five miles. A light rain began to fall. Warnings about the dangerous downdrafts behind a steaming carrier were broadcast blind in both Vietnamese and English—hoping the pilot could somehow hear them even though he had no radio.

Buang-Ly lined up his approach.

He had never landed on an aircraft carrier before. The runway was 1,001 feet long—enormous for a carrier, impossibly small for what he was attempting. The downdraft behind the ship could slam his overloaded plane into the deck or flip it over the side. He had one chance.

He looked at his family.

“When I looked at my family,” he said later, “my gut told me I could do it.”

He pushed the throttle forward and began his descent.

The Bird Dog crossed the ramp, bounced once on the deck, touched down in the exact spot where the arresting wires would normally have been, and rolled forward. The flight deck crew sprinted toward the plane, ready to grab it before it went over the angle deck.

They didn’t need to. Buang-Ly brought the Cessna to a stop with room to spare.

The crew erupted in cheers.

And then something unexpected happened. Major Buang-Ly and his wife jumped out of the cockpit, pulled the backseat forward—and out tumbled child after child after child. The deck crew had expected two passengers. They watched in amazement as five small children emerged from a plane built for one.

Captain Chambers came down from the bridge. He walked up to the exhausted pilot, this man who had risked everything on an impossible gamble, and did something that no regulation authorized but every sailor understood.

He pulled the gold wings from his own uniform and pinned them on Buang-Ly’s chest.

“I promoted him to Naval Aviator right on the spot,” Chambers said.

The crew of the Midway adopted the family. They collected thousands of dollars to help them start their new life in America. The Buang family became seven of the estimated 130,000 Vietnamese refugees who eventually resettled in the United States. All seven are now naturalized American citizens.

Captain Lawrence Chambers was never court-martialed. He was promoted to Rear Admiral and retired in 1984 as the first African American Naval Academy graduate to reach flag rank. Today, at ninety-six years old, he still speaks about that day with the same conviction.

“You have to have the courage to do what you think is right regardless of the outcome,” he said at a recent commemoration. “That’s the only thing you can live with.”

Major Buang-Ly, now ninety-five, lives in Florida. The Bird Dog he flew that day hangs from the ceiling of the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, still bearing its South Vietnamese markings. Beside it, in a display case, is the crumpled note he dropped onto the deck of the Midway.

Fifty years later, both men—the pilot who refused to let his family die and the captain who refused to let them drown—are still here to tell the story.

Some moments become symbols larger than themselves. This was one of them. Not just an escape, but a testament to what becomes possible when desperate courage meets uncommon decency.

A father who would not give up. A captain who would not look away.

And a flight deck cleared for landing.