During the filming of the aquatic number in “Footlight Parade” (1933), a female dancer slipped under the water during a synchronized sequence. Dozens of dancers moved in unison in the large studio tank, but James Cagney, standing nearby in costume, noticed something off in her movement. Without a pause, he leapt into the water in full wardrobe and reached her before anyone else reacted. Crew members rushed in with towels, but it was Cagney who had already pulled her to the surface, gasping and pale.

She later said, “If it weren’t for Jimmy, I’d be dead. He never blinked. Jumped in like a lifeguard.” Cagney brushed it off with a grin, saying anyone else would have done the same, but those who knew him disagreed.

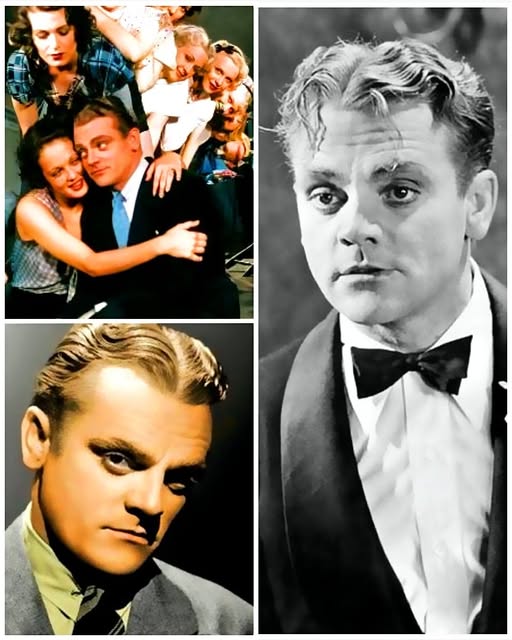

James Cagney was known for playing gangsters and fast-talking tough guys, but in real life, he was quiet, gentle, and fiercely loyal. His longtime friend and frequent co-star Pat O’Brien once told a reporter, “Jim was the only man I knew who could talk down a bar brawl and then go home to read poetry.” That combination of steel and softness defined much of who Cagney was behind the camera.

During the shooting of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” (1942), a young extra on set slipped while coming down the soundstage steps. Cagney was already in costume, practicing lines alone on stage. When he saw her fall, he hurried over, helped her up, and spent twenty minutes sitting with her while a studio nurse arrived. The extra, decades later, recalled that Cagney stayed with her even after the nurse said she’d be fine. “He asked if I was embarrassed and told me not to be,” she remembered. “He said everyone stumbles in this town—what matters is how quick you get up.”

Born July 17, 1899, in New York City, James Francis Cagney Jr. grew up in a rough neighborhood on the Lower East Side. His father, a bartender and amateur boxer, died young. His mother supported the family by working as a cleaner and boarding house manager. Cagney’s early years were filled with hardship, but he often said his mother taught him compassion by action, not lecture. He recalled how she once brought home a beggar from the street and made him a full dinner.

That memory stayed with him, shaping how he treated the people around him throughout his life.

Even at the height of his fame, he maintained friendships with grips, electricians, and drivers. On the set of “Each Dawn I Die” (1939), a gaffer lost his mother and couldn’t afford to travel back home for the funeral. Cagney overheard the conversation and quietly handed the man an envelope with train fare and extra cash.

He never mentioned it again.

When a studio executive tried to replace a background dancer because she had fallen behind in rehearsal, Cagney stepped in. He had watched her push through an ankle injury and asked that she be given another chance. “She’s part of this picture too,” he reportedly told the director. “You don’t cut out family when they’re limping.”

His affection for dancers and the chorus crew was widely known, possibly because his own early career began in vaudeville. Before the suits and Tommy guns, Cagney tapped his way across stages, performing comedy and dance routines that earned him just enough for rent. He never forgot those beginnings.

In later years, when asked about his proudest moment in Hollywood, Cagney didn’t mention awards or critical acclaim. He quietly referred to the dancer he pulled from the water on “Footlight Parade.” “She had a family,” he said. “She went home that night. That’s all that mattered.”

Cagney’s instincts weren’t rehearsed. They came from a place deeper than performance—from the streets that raised him, from the mother who fed strangers, and from a lifetime of watching for people who needed a hand before they asked for it.