A single PFAS chemical featured in the movie “Dark Waters” last year about contamination from a Teflon plant in Parkersburg, W.Va. resulted in a $670 million court settlement. A community study showed the chemical was linked to six diseases: kidney cancer, increased cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, preeclampsia and testicular cancer.

But that chemical, PFOA, is just one of the more than 4,000 types of PFAS chemicals that scientists believe could undermine human health across the world. While most researchers study a handful of these chemicals at most, Carla Ng is one of the few scientists trying to find an approach that works for all of them.

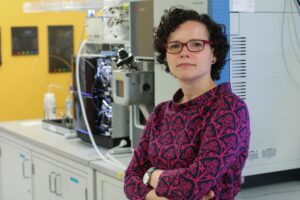

“So without a lot of data, how are we going to tackle all these?” Ng, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, asked a group of scientists at a PFAS toxicology conference in 2019, where she was the only scientist invited to give two presentations.

To make headway, Ng is building more sophisticated animal models and studying the chemicals through computer simulations. But it is not enough to research how these chemicals might be bad for us, she said, since many chemicals are already polluting the environment. So she is helping to track where the chemicals are being used and looking for new ways to clean them up.

https://www.publicsource.org/pitt-scientist-toxic-pfas-4000-chemical-contamination/