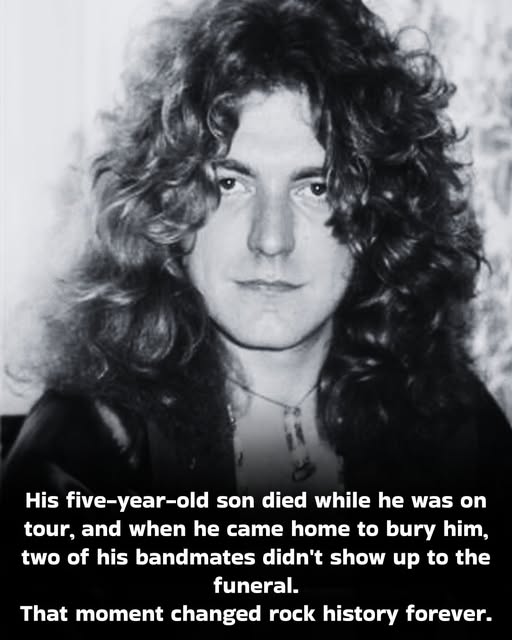

His name was Robert Plant, and on July 26, 1977, he received the phone call that would redefine everything he thought mattered.

He was in New Orleans with Led Zeppelin—the biggest band on Earth. They’d just sold out stadiums across America. Millions of dollars. Infinite momentum. The machine had no off switch.

Then his wife called.

The first call said their five-year-old son Karac was sick—a stomach virus, nothing unusual.

The second call came hours later.

Karac was dead.

Robert Plant—the golden god of rock, the voice that defined a generation, the man who seemed untouchable—fell apart in a hotel room half a world away from where his child had taken his last breath.

There was no warning. No goodbye. Just a sudden infection that killed a healthy five-year-old boy in a matter of hours while his father sang for strangers.

The tour was cancelled immediately. Plant flew home to England.

And when he arrived to bury his son, only one of his three bandmates showed up.

John Bonham—Led Zeppelin’s drummer—came to the funeral. Bonham’s wife Pat came. They stood with Plant’s family through the unbearable.

Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones did not come.

Different accounts exist about why. Some say Page was on a bender. Others say Jones was on vacation. Page later said, “We were all mates. We had to give the man some space.”

But Plant didn’t want space.

He wanted his friends.

Years later, Plant would say about that absence: “The other guys were from the South [of England], and didn’t have the same type of social etiquette that we have up here in the North that could actually bridge that uncomfortable chasm with all the sensitivities required.”

He was more blunt with tour manager Richard Cole: “Maybe they don’t have as much respect for me as I do for them. Maybe they’re not the friends I thought they were.”

Biographer Mick Wall wrote: “Until then, Robert was still in thrall to Jimmy and what he had created with Zeppelin. After that incident, Jimmy no longer held the same mystique for Robert. It was also the beginning of Robert having much more power over what the band did or didn’t do next. He truly no longer cared and therefore was ready to walk at any point.”

Something fundamental broke.

Plant retreated home with his wife Maureen and daughter Carmen. He stopped everything—the drugs, the alcohol, the persona. “I stopped taking everything on the same day,” he said later. “The most important thing to me is my family and when I got off my face, I found it difficult to be all things to the people that meant a lot to me.”

He told Rolling Stone: “I lost my boy. I didn’t want to be in Led Zeppelin. I wanted to be with my family.”

Plant applied for a job at a Rudolph Steiner training college in Sussex. He was serious about walking away from rock entirely. The man who’d sung “Immigrant Song” and “Whole Lotta Love” to millions wanted to teach children in a quiet English countryside school.

“I just thought: ‘What’s it all worth? What’s that all about? Would it have been any different if I was there—if I’d been around?'” Plant recalled. “So I was thinking about the merit of my life at that time, and whether or not I needed to put a lot more into the reality of the people that I loved and cared for.”

John Bonham convinced him to return—not with arguments about duty or money, but with friendship.

“After the death of my son Karac in 1977, I received a lot of support from Bonzo,” Plant said. “He had a six-door Mercedes limousine and it came with a chauffeur driver’s hat. We lived five or six miles apart, and sometimes we’d go out for a drink. He’d put the chauffeur driver’s hat on and I’d sit in the back of this stretch Mercedes and we’d go out on the lash. Then he’d put his hat back on and drive me home.”

Bonham would drive past police while drunk, and the cops would wave them through: “There’s another poor fucker working for the rich!”

“He was very supportive at that time, with his wife and the kids,” Plant said. “So I did go back for one more flurry.”

But Plant was different when he returned. The swagger was gone. The mythology felt obscene.

“I didn’t really want to go swinging around,” he said. “‘Hey hey mama, say the way you move’ didn’t really have a great deal of import anymore.”

Led Zeppelin released one more album—In Through the Out Door in 1979. Plant wrote “All My Love” about Karac, a song that became both tribute and testimony to what had been lost.

“I think it was just paying tribute to the joy that he gave us as a family and, in a crazy way, still does occasionally,” Plant told Dan Rather decades later. “His mother and I often… the memory gets… changes, the contrast and the focus changes as time goes on. It’s a long time ago that we lost him. 40 years ago.”

Plant and his wife had another son, Logan, in 1979. “We were blessed with another boy who came along about two years later and the two images are blurred. The definition between Karac and Logan is—it’s a tough one to chip through the two things, but he was a little nature boy, you know? He was a mountain man.”

In 1980, Led Zeppelin prepared for their first North American tour since Karac’s death.

On September 24, 1980, John Bonham—Plant’s closest friend in the band, the man who’d sat with him through the darkest grief—arrived at rehearsals and began drinking.

He didn’t stop.

By midnight, Bonham had consumed approximately 40 shots of vodka—roughly 1.5 liters of alcohol in 12 hours.

He passed out. Someone put him to bed on his side.

The next morning, September 25, 1980, tour manager Benji LeFevre and bassist John Paul Jones found Bonham dead. He’d choked on his own vomit during sleep. He was 32 years old.

On his last day alive, driving to what would be his final rehearsal, Bonham had told Plant: “I’ve had it with playing drums. Everybody plays better than me. I’ll tell you what, when we get to the rehearsal, you play the drums and I’ll sing.”

The North American tour was cancelled.

On December 4, 1980, Led Zeppelin issued a statement:

“We wish it to be known that the loss of our dear friend and the deep respect we have for his family, together with the sense of undivided harmony felt by ourselves and our manager, have led us to decide that we could not continue as we were.”

Led Zeppelin was over.

No farewell tour. No final album. No goodbye spectacle.

The most profitable band in rock history simply stopped.

For decades afterward, the offers came. Reunion tours worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Festival headlining spots. Record-breaking paydays. Every offer bigger than the last.

Plant said no to all of them.

Fans called him selfish. Ungrateful. Cowardly. The industry kept waiting for him to crack, to need the money, to miss the glory enough to resurrect the machine.

He never did.

Instead, Plant did something radical: he dismantled the voice that made him famous.

He lowered his range. Abandoned the scream. Explored folk, bluegrass, world music, African rhythms. He collaborated with Alison Krauss on Raising Sand—an album of quiet, intimate songs that won five Grammy Awards including Album of the Year.

Critics called it decline. Plant called it survival.

“I couldn’t be that man anymore,” he said. “He died with my son.”

People remember Robert Plant as the golden god of Led Zeppelin—shirtless, screaming, invincible. That image freezes him in 1973, before the damage, before the loss, before the choices that revealed who he actually was.

His real legacy is harder and more important.

He proved that sometimes the most shocking act isn’t destruction—it’s refusal.

Refusal to monetize grief.

Refusal to let momentum consume the people caught in it.

Refusal to resurrect something that only survives by killing parts of the people inside it.

This story matters because it exposes a truth most people live with quietly: the world will keep asking you to return to what worked, even when returning would destroy what’s left of you.

Plant didn’t fade away. He didn’t burn out in a dramatic collapse.

He stopped.

He walked away from the most profitable brand in music history because his child mattered more than the mythology.

He refused reunion tours worth hundreds of millions because he’d already learned what momentum costs.

He changed his art entirely because staying the same would have required becoming someone he could no longer be.

In an industry built on endless resurrection, on squeezing every dollar from nostalgia, on never letting the machine stop—Robert Plant’s decision to simply walk away remains the most radical thing he ever did.

Not the screams. Not the stadiums. Not the golden god mythology.

The refusal.

The quiet, permanent, non-negotiable refusal to sacrifice what remained of his humanity for what the audience wanted.

Forty-five years later, Robert Plant is 76 years old. He still makes music. Still tours. Still creates.

But he’s never been Led Zeppelin again.

And he never will be.

“Every now and again Karac turns up in songs,” Plant said in 2018, “for no other reason than I miss him a lot.”

That’s the real Robert Plant.

Not the golden god frozen in 1973.

The father who buried his five-year-old son, lost his best friend three years later, and chose to protect what was left rather than feed it to the machine that wanted more.