(Tom: The really important thing that determines a man’s productive capacity is, can he learn and can he accurately apply what he learns to produce the desired product.)

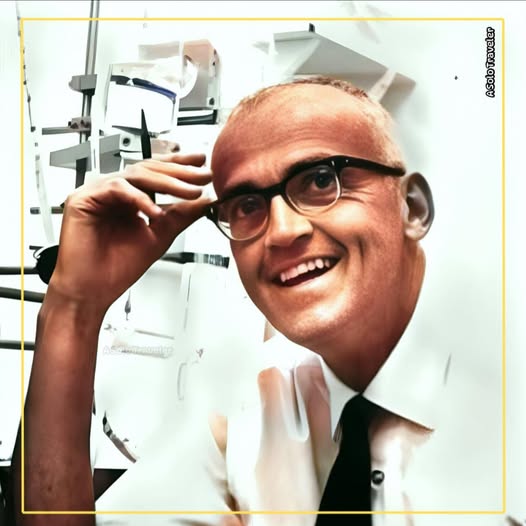

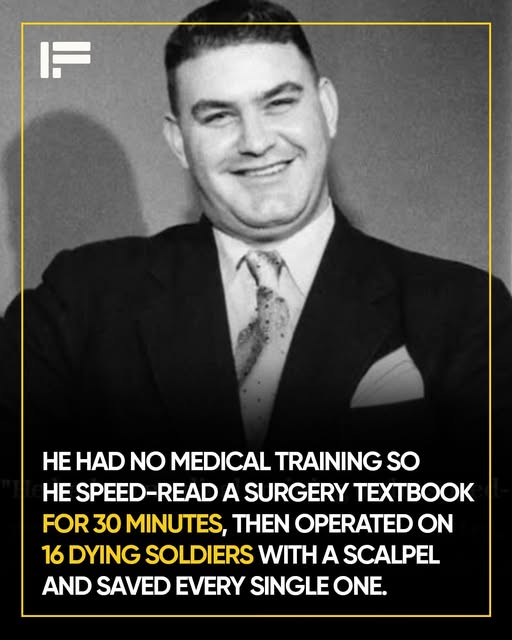

He had no medical degree. No surgical training. No license of any kind.

And yet, after half an hour with a textbook, he picked up a scalpel and saved the lives of sixteen wounded soldiers.

The wounded arrived just before nightfall in 1951, during the Korean War.

A small South Korean junk eased alongside the HMCS Cayuga, a Canadian destroyer operating off the Korean coast. Inside were guerrilla fighters from a failed commando raid. Some were torn open by shrapnel. One man had a bullet lodged dangerously close to his heart. Another had injuries so severe that amputation was the only chance of survival.

The crew turned instinctively to the ship’s surgeon, a calm, capable man serving under the name Joseph Cyr.

There was only one problem.

He wasn’t Joseph Cyr.

And he wasn’t a doctor.

The man wearing the surgeon’s uniform was Ferdinand Waldo Demara, an American with no medical training whatsoever. Months earlier, he had stolen the real Dr. Joseph Cyr’s identity and credentials and used them to enlist in the Royal Canadian Navy, which was urgently recruiting medical officers for wartime service.

Now his deception had reached its breaking point.

Demara understood the stakes immediately. If he confessed, the wounded men would almost certainly die before help could arrive. If he tried to operate, he could kill them himself.

He chose to operate.

He ordered the crew to prepare the patients for surgery and retreated to his cabin. There, he opened a medical textbook and began reading with ferocious concentration, focusing on wound extraction, chest surgery, and emergency amputation. His entire surgical education lasted about thirty minutes.

Then he walked into the operating room.

Throughout the night, Demara performed one operation after another. He removed shrapnel. He closed deep wounds. He amputated a crushed foot. He extracted a bullet from a man’s chest, working perilously close to the heart. He relied on anatomy diagrams, logic, nerve, and an extraordinary ability to absorb information quickly.

When morning came, every single patient was alive.

The crew believed they had witnessed something close to a miracle and began preparing a recommendation for a commendation. That decision would ultimately expose him.

Ferdinand Demara was no ordinary impostor.

Born in 1921 in Massachusetts, he grew up during the Great Depression, watching his family fall from comfort into hardship. As a teenager, he ran away to join a monastery. When that life no longer suited him, he reinvented himself again and again.

Over the years, Demara successfully passed himself off as a monk, a psychology professor, a prison warden, a lawyer, a cancer researcher, and an engineer. He possessed an exceptional memory, remarkable intelligence, and a keen understanding of institutional behavior. He learned how professionals spoke, how authority sounded, and how confidence discouraged scrutiny.

He lived by two rules: never volunteer unnecessary information, and project certainty at all times.

When Demara joined the Royal Canadian Navy under a stolen identity, no one questioned him. Canada needed doctors. The war accelerated paperwork. His credentials were accepted at face value.

Aboard the Cayuga, Demara improvised constantly. When sailors came to him with ailments, he would excuse himself, sprint to his cabin, consult textbooks, and return with a confident diagnosis. He treated many conditions with penicillin, which was widely used at the time. When the ship’s captain needed teeth extracted, Demara performed the procedure successfully, earning praise for his steady hand.

But it was the night of the guerrillas that sealed his legend.

Ironically, his success led to his exposure. Canadian newspapers praised “Dr. Joseph Cyr” for his heroism. One reader was the real Dr. Cyr’s mother, who knew her son was safely practicing medicine in New Brunswick. She contacted authorities. An investigation followed.

When confronted, Demara collapsed under the pressure. He secluded himself for days, sedated, before finally surrendering.

The Royal Canadian Navy faced embarrassment of its own making. Prosecuting Demara would highlight their failures, so they quietly discharged him, paid him in full, and deported him to the United States without charges.

In 1961, Hollywood dramatized his life in The Great Impostor, starring Tony Curtis. The fame ended Demara’s ability to disappear into new identities, but it also changed how people viewed him.

Years later, when Demara attended a reunion of the Cayuga crew, the sailors welcomed him warmly. They remembered him not as a fraud, but as the man who saved lives when no one else could.

Demara spent his final years as a legitimately ordained hospital chaplain in California. He died in 1982 at age sixty.

The question remains unsettled.

Was Ferdinand Demara a criminal, or was he a hero?

Was he reckless, or was he brilliant under pressure?

Do credentials define competence—or does action?

For sixteen wounded men on a ship in Korean waters, the answer was simple.

He showed up.

He acted.

And they lived.