“The reward of a thing well done is having done it.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson, Poet (1803 – 1882)

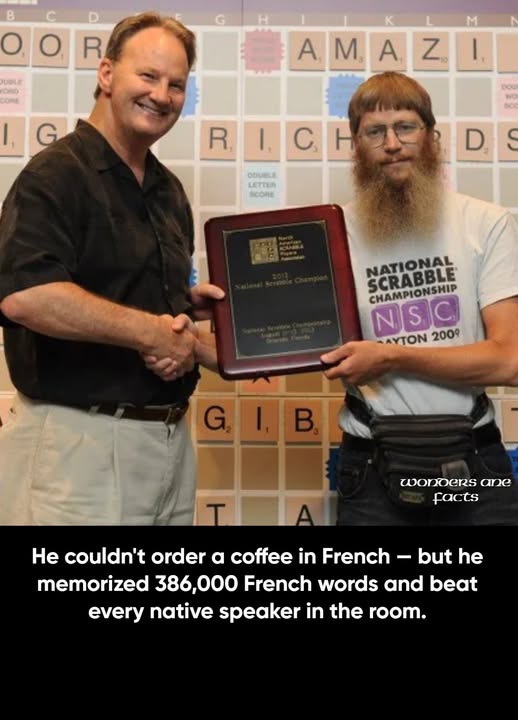

Nigel Richards

In July 2015, a quiet man from New Zealand walked into a Scrabble tournament in Belgium. He sat down across from the best French-speaking Scrabble players on Earth. He could not ask them how their day was going. He could not read a French menu. By his own friends’ account, he could barely count to ten and say “bonjour.”

Nine weeks earlier, Nigel Richards had decided to do something that no one in the history of competitive Scrabble believed was possible. He would enter the French-language Scrabble World Championship — without speaking a single word of French.

His method was as audacious as it was simple. The French Scrabble dictionary contains roughly 386,000 words — more than double the 187,000 in the North American English version. Richards did not learn what any of them meant. He sat with the dictionary and absorbed the words as pure visual patterns — sequences of letters arranged on a page. He didn’t need to know that “miauler” means “to meow.” He just needed to know it existed and where its letters could land on a board.

How was this possible? People who have known Richards for decades say his brain simply works differently than most. The secretary of his first Scrabble club in Christchurch explained that Richards can look at a page and retain the whole thing, like a photograph. Richards himself once described it more precisely: he can recall images very easily, but only if he’s seen them. If he’s only heard a word, it doesn’t stick. But if he sees it once on a page, he can bring it back.

He won 14 of 17 preliminary games. Then he defeated the previous year’s runner-up in the final. The French Scrabble Federation’s official announcement switched to English just to say: “Congratulations Nigel, you’re amazing!”

But Richards wasn’t finished.

He won the French championship again in 2018, proving the first time was no fluke.

Then he turned his attention to Spanish.

He spent about a year memorizing the Spanish Scrabble word list. When he arrived at the 2024 Spanish World Championship in Granada, native speakers doubted whether a non-Spanish speaker could seriously compete at the highest level. Richards answered by winning 23 of his 24 games. The defending champion, who finished second with 18 wins, called it a humiliation for every native speaker in the competition. The tournament organizer said Richards had simply shut their mouths completely.

One competitor captured what it feels like to face him. He said that when Nigel Richards sits down at a table, everyone loses their nerves — even the biggest champions. That playing against him is like playing against a computer.

What makes Richards truly extraordinary isn’t just the memorization. It’s everything surrounding it. He already held five English-language World Scrabble Championships when he decided to conquer French. He has won nearly 200 tournaments across his career. He once simultaneously held the World, American, and British titles. In competitive Scrabble, there is Nigel Richards, and then there is everyone else.

Yet he does not give interviews. He does not seek attention. He reportedly lives simply in Malaysia, without television or radio, spending hours cycling and studying word lists. When journalists request interviews through his friends, he declines because he doesn’t understand what all the fuss is about. When asked after one tournament what he planned to do next, he mentioned there was a very good library nearby.

His mother once told a New Zealand newspaper something that says everything about how his mind works: she didn’t think her son had ever read a book, apart from the dictionary.

He was introduced to Scrabble at twenty-eight because his mother was tired of him counting cards when they played the card game 500. She thought Scrabble would be harder for him because he’d never been good at English in school. She was wrong. He joined a local club in Christchurch and was very soon beating everyone there. For his first national championship in 1997, he cycled 220 miles to the tournament — and won.

Nigel Richards doesn’t see words the way you and I do. He doesn’t see meaning. He sees structure. He sees possibility. He sees patterns where others see a foreign language, and solutions where others see an impossible wall.

He reminds us of something we too easily forget: that the boundaries we accept are often the boundaries we build. He didn’t speak French. He didn’t speak Spanish. He didn’t need to. He found another path — one built on discipline, memory, and the quiet certainty that what everyone else called impossible was simply a problem he hadn’t solved yet.

The next time you tell yourself something can’t be done, remember the man who memorized hundreds of thousands of words he couldn’t understand and defeated every native speaker in the room.

Then ask yourself what you might accomplish if you stopped believing in the wall.

The Wise Build Bridges

Quote of the Day

“Do something wonderful, people may imitate it.” – Albert Schweitzer, Humanitarian (1875 – 1965)

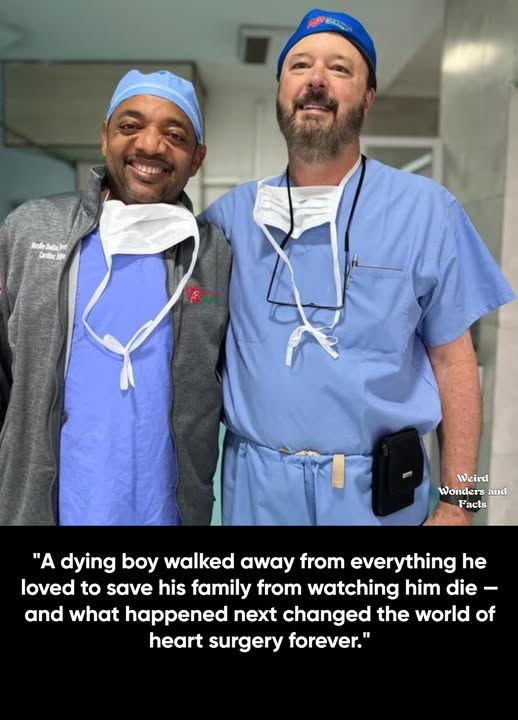

Mesfin and Allen – A Story of Courage and Compassion

A dying boy walked away from everything he loved to save his family from watching him die — and what happened next changed the world of heart surgery forever.

Mesfin Yana was born in 1985 in Shafina, a tiny village in southern Ethiopia. There were no cars, no electricity, no running water. His family were coffee farmers. He had thirteen brothers and sisters. And by every measure that mattered to him, he was happy.

Then, around the age of ten or eleven, he got a sore throat. It seemed like nothing. But in a place with no hospitals and no antibiotics, nothing can become everything. That untreated strep throat quietly turned into rheumatic fever, and rheumatic fever slowly destroyed the valves of his heart.

By the time Mesfin was fifteen, he was dying.

His parents took him to a local doctor, who could only deliver the truth: the boy needed heart surgery, and there was no heart surgeon in the entire country for nearly a hundred million people. There was nothing anyone could do.

So Mesfin made a decision that no child should ever have to make. Rather than force his family to watch him waste away, he left home. He walked miles from his village to the city of Awassa, alone, sick, and barely strong enough to stand. A local shelter run by Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity took him in, and later transferred him to another shelter in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa.

There, his condition continued to worsen — until one day, an American doctor named Rick Hodes walked through the door. Dr. Hodes, an internist who had spent decades caring for the poorest patients in Ethiopia, examined Mesfin and diagnosed him with severe congestive heart failure. The boy’s heart was failing. But Dr. Hodes refused to accept that as the ending.

He reached out to his colleague and close friend in Atlanta — cardiologist Dr. Allen Dollar — and together they arranged for Mesfin to fly to the United States for open-heart surgery. At Piedmont Heart Institute, cardiothoracic surgeon Dr. Jim Kauten repaired Mesfin’s damaged mitral valve.

The surgery was a success. Mesfin returned to Ethiopia, and for a brief, beautiful moment, it seemed like the story had its happy ending.

It didn’t. Not yet.

Six weeks later, Mesfin developed a dangerous infection called endocarditis — an inflammation of the heart lining triggered by a dental procedure he’d had while in the U.S. His repaired valve was being destroyed all over again. Dr. Hodes contacted Dr. Dollar, and once more, the two doctors pulled Mesfin back to Atlanta.

This time, during surgery, the team discovered the valve was beyond saving. They replaced it with a mechanical one — a device that would keep him alive but required lifelong blood thinners and constant medical monitoring. The kind of monitoring that simply did not exist in rural Ethiopia.

Mesfin could not go home.

Dr. Allen Dollar called his wife, Shelly, from the hospital. “I think we’re going to have another kid,” he said.

The Dollars were no strangers to opening their home. They already had biological daughters and adopted children from China, El Salvador, and Mexico — many with serious health conditions. Mesfin joined their family in Atlanta, eventually taking their last name. He later said it reminded him of home: “This is as large a family as I had back in Ethiopia.”

And then, quietly, something remarkable began to happen.

Mesfin studied harder than anyone the Dollars had ever seen. He learned English, caught up to his peers, and threw himself into academics with a focus that stunned his teachers. He enrolled at Georgia State University to study respiratory therapy. There, he met his future wife, Iyerusalem. They married and had two sons.

But Mesfin wasn’t done. He moved his young family to Texas and trained as a cardiac perfusionist at the Texas Heart Institute — learning to operate the heart-lung machine, the very device that had kept him alive during his own surgeries. He eventually landed a position at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, where he now runs heart-lung machines during some of the most complex open-heart surgeries performed anywhere in the world. His wife works there too, as a cardiac sonographer.

The first time Mesfin assisted in surgery, his patient was a teenage girl from Ethiopia. She was terrified, crying on the operating table. He walked to her bedside and spoke to her in Amharic. “I had the same surgery,” he told her gently. “Things are going to be just fine.”

Years later, he still sees himself in every patient. “I was on that same operating table,” he says.

Today, Mesfin flies back to Ethiopia regularly alongside Dr. Jim Kauten — the very surgeon who once opened his chest to save his life. Together, through the nonprofit Heart Attack Ethiopia, they perform life-saving heart surgeries for patients who, like Mesfin once was, have no other option. He serves not only as a perfusionist but as an interpreter between Ethiopian and American medical teams, bridging two worlds that shaped him.

He also did something else that speaks to who he truly is: he helped bring his biological parents and several of his siblings to the United States, reuniting the family he once walked away from to protect.

“I’m always grateful,” Mesfin says. “I’m grateful for my family, for just being in the United States. It’s a resurrection for me. You know, I was once lost, dead, and I was resurrected and I’m living a new life.”

His adoptive father, Dr. Allen Dollar, puts it simply: “He has retained this spirit of gratitude. He has never lost sight of what his life could have been, and all the people along the way.”

Mesfin Yana Dollar was once a dying boy who walked away from home so his family wouldn’t have to watch him go. Today, he stands in operating rooms at one of the world’s greatest hospitals, keeping hearts beating with the same machine that once kept his own alive.

Some people are saved so they can save others. Mesfin is living proof.

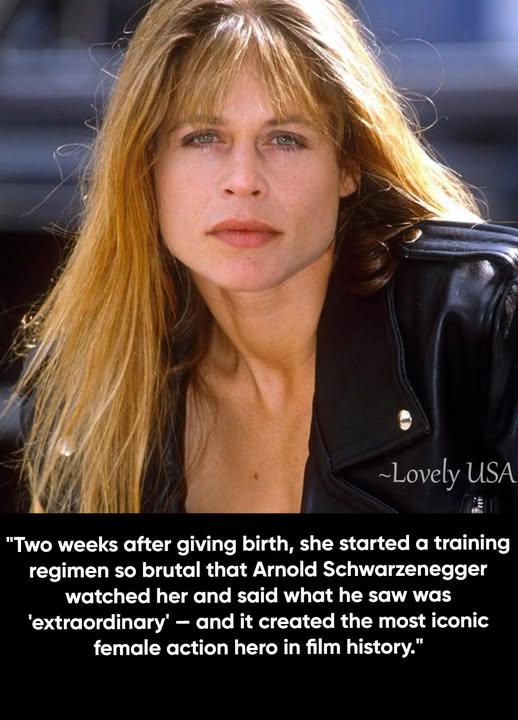

Linda Hamilton as Sarah Connor

Two weeks after giving birth, she started a training regimen so brutal that Arnold Schwarzenegger watched her and said what he saw was “extraordinary“ — and it created the most iconic female action hero in film history.

In 1984, Linda Hamilton walked onto the set of a low-budget science fiction film and played a waitress named Sarah Connor. The character was ordinary by design — a young woman living a quiet life in Los Angeles who is suddenly hunted by an unstoppable cyborg from the future. Sarah spends most of the film terrified, running, screaming, and barely surviving. She is not a warrior. She is everywoman — caught in a nightmare she can’t understand.

The film was called The Terminator. It was directed by a young James Cameron on a modest budget. Nobody expected it to become a phenomenon. But it did — grossing over $78 million worldwide and launching one of the most successful franchises in cinema history.

When Cameron called Hamilton back for the sequel seven years later, he had a radical vision. Sarah Connor would be completely different. The terrified waitress was gone. In her place would be a woman forged by knowledge of the coming apocalypse — someone who had spent the intervening years preparing for a war that only she knew was coming. A woman who had been institutionalized for telling the truth. A woman who had become, in Cameron’s own words, “the Terminator of the second film, at least on a psychological level.“

Hamilton didn’t just agree to this transformation. She demanded it. She wanted Sarah Connor to be just as physically capable and dangerous as Schwarzenegger’s cyborg. She wanted to do her own stunts. She wanted the audience to believe, without question, that this woman could fight, shoot, and survive anything the future threw at her.

And then she did something that still amazes people who hear it for the first time.

Just two weeks after giving birth to her son Dalton, Linda Hamilton began training.

For thirteen weeks — and continuing throughout the entire production — she trained three hours a day, six days a week. Her regimen was punishing: running, biking, swimming, stair climbing, free weights, trampoline drills, walking lunges, and extensive abdominal work, all under the guidance of personal trainer Anthony Cortés. She shed twelve pounds of fat and built visible, functional muscle that redefined what audiences expected a woman to look like on screen.

But that was only half of it.

Hamilton also hired Uzi Gal, a former Israeli special forces commando, to train her in military tactics and weapons handling. She learned judo. She learned how to load clips, change magazines, clear a room upon entry, and verify kills. She trained until she could bench press eighty-five pounds for repetitions, run eight miles, and pump-load a twelve-gauge shotgun with one arm.

When Schwarzenegger — a man who had spent his life in the world of physical fitness and bodybuilding — watched Hamilton train, he was genuinely impressed. He later recalled thinking that what he witnessed was extraordinary, even by his standards.

The result, when cameras rolled on Terminator 2: Judgment Day in 1991, was something Hollywood had never seen before.

In the film’s most iconic introduction, Sarah Connor does pull-ups in a locked cell in a psychiatric institution, her arms lean and corded with muscle, her face empty of anything except focused determination. It’s a single image that tells the audience everything has changed. This is not the same woman. This is not someone who needs to be rescued. This is someone you do not want to cross.

Hamilton’s performance went far beyond the physical. She gave Sarah Connor a psychological depth that elevated the entire film. The scene where Sarah nearly assassinates Miles Dyson — the innocent scientist whose work will eventually lead to the destruction of humanity — is devastating not because of the action but because of what it reveals about what fear and knowledge have done to her. She has become something terrifying herself. And Hamilton plays that moral complexity with a rawness that never flinches.

She also suffered real consequences for her commitment. During filming, Hamilton fired a gun inside an elevator without her ear plugs in place. The blast caused permanent hearing damage in one ear — an injury she carries to this day.

Terminator 2 grossed over $500 million worldwide and is widely regarded as one of the greatest action films ever made. Hamilton’s portrayal of Sarah Connor became a cultural landmark — the definitive female action hero alongside Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley in the Alien franchise.

But after the film’s triumph, something Hamilton had predicted came true. She was immediately offered a flood of “Terminator imitations“ — tough-woman roles that wanted her body and her intensity but not her range. She tried to build a broader career. She starred opposite Pierce Brosnan in the disaster film Dante’s Peak. She took television roles. She appeared on stage. But the shadow of Sarah Connor was long, and Hollywood’s imagination for what she could do remained stubbornly narrow.

Hamilton eventually stepped away from the spotlight entirely, moving to New Orleans to live what she called “a lovely, authentic life“ far from Los Angeles. She was open about her struggles, including her diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and she found peace in a quieter existence.

Then, in 2019, at the age of sixty-three, she came back.

James Cameron called. There was a new Terminator film — Dark Fate. Cameron wanted her. Hamilton was deeply reluctant. She had built a life she loved. She didn’t want to play the Hollywood game again. And above all, as she told the New York Times, she was afraid — not of disappointing fans, but of disappointing the character: “I was afraid to let Sarah Connor down.“

She agreed — on the condition that she would help shape who Sarah had become. And then she did it all over again. She spent a full year training with Mackie Shilstone — the legendary performance coach who had trained Serena Williams and Peyton Manning. At sixty-one years old, she submitted to a comprehensive program of weight-lifting, Pilates, cross-training, and a strict diet that eliminated carbohydrates for an entire year. She worked with a cardiologist, a physical therapist, and a dietitian. She trained with an Army Ranger to relearn weapons handling.

Cameron had told Shilstone something that fueled the entire effort: he wanted to change Hollywood’s habit of “throwing female actors away after the age of forty.“

Hamilton walked back onto a Terminator set nearly three decades after her legendary T2 transformation and proved, once again, that Sarah Connor was not a role. It was a standard.

Most recently, in 2025, Hamilton appeared as Dr. Kay in the final season of Netflix’s Stranger Things — a villainous military researcher — adding yet another dimension to a career that Hollywood once tried to reduce to a single character.

Linda Hamilton didn’t just play Sarah Connor. She became her — at a physical cost, an emotional cost, and a professional cost that most audiences never saw. She trained harder than almost any actress in history. She sacrificed her hearing for a single scene. She walked away from fame to protect her own sanity. And when the world asked her to come back, she did it again at sixty-three — not for the money or the applause, but because she wouldn’t let anyone else diminish what she had built.

She once said, after completing T2: “I don’t think anything can hurt me.“

Looking at what she’s endured and what she’s achieved, it’s hard to argue with her.

Discipline

“Discipline isn’t punishment — it’s self-respect. It’s choosing your future over your feelings, over and over again.” – Elena Cardone

“Self-discipline is the ability to make yourself do what you should do, when you should do it, whether you feel like it or not.” – Elbert Hubbard

Step Away From The System

Here is a blueprint of specific, actionable steps to help you do exactly that: https://howtolivethehealthiestlife.com/

Quote of The Day

“The strength or weakness of a society depends more on the level of its spiritual life than on its level of industrialization. Neither a market economy nor even general abundance constitutes the crowning achievement of human life. If a nation’s spiritual energies have been exhausted, it will not be saved from collapse by the most perfect government structure or by any industrial development. A tree with a rotten core cannot stand.” – Alexander Solzhenitzyn

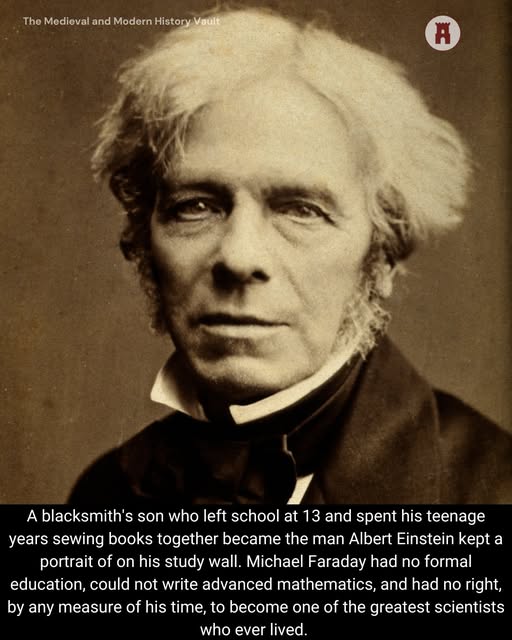

Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday was born in 1791 in Newington Butts, south London, the son of a blacksmith who was frequently too ill to work. The family was often hungry. His education consisted of learning to read, write, and do basic arithmetic at a church Sunday school, and that was where it ended. At the age of 13 he was running errands for a bookbinder and bookseller. At 14 he was apprenticed to the man, George Riebau of Blandford Street, Marylebone, for a seven-year term. Unlike every other apprentice in that shop, Faraday read every book that came in to be bound.

He read the entry on electricity in the third edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and was so captivated that he built himself a crude electrostatic generator out of old bottles and lumber. He read Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry and began conducting his own chemical experiments. He joined the City Philosophical Society in 1810, a group of young working men who met weekly to hear lectures on science and discuss what they had learned. He was educating himself in the only way available to him, from the inside of a trade he had no intention of staying in.

In 1812, a customer at the bookshop gave the 20-year-old Faraday four tickets to attend lectures at the Royal Institution by Sir Humphry Davy, then the most celebrated chemist in Britain. Faraday attended every one, taking meticulous notes in the careful hand of a man who had taught himself to write properly. He bound those notes into a beautiful 300-page volume and sent them to Davy with a letter asking for any position in science, however small. Davy wrote back kindly but said there was nothing available.

Then, a few months later, Davy’s laboratory assistant was dismissed after getting into a fight. Davy remembered the eager young bookbinder. In March 1813, Faraday was hired as a laboratory assistant at the Royal Institution at 25 shillings a week, two rooms in the attic, and the use of the laboratory. It was, in the judgment of history, one of the most consequential hiring decisions ever made.

Within a year, Davy took Faraday on an 18-month tour of Europe, where he met many of the leading scientists of the age. Back in London, Faraday began his own research. In 1821 he invented the electric motor, demonstrating that electrical current could produce continuous mechanical motion, a concept nobody had achieved before. By 1831 he had made the discovery that would change the world: electromagnetic induction. By passing a magnet through a coil of wire, he generated an electric current. This was the first electrical generator, the foundational principle behind every power station ever built.

He went on to discover the laws of electrolysis, coined the terms electrode, anode, cathode, and ion, discovered benzene, invented the Faraday cage that today lines microwave ovens and MRI scanners, and demonstrated the first known connection between light and magnetism. He had no formal education. He could not write mathematics. He worked entirely through experiment and physical intuition, visualising invisible lines of magnetic force moving through space in ways that mathematical physicists initially dismissed as mystical, and that James Clerk Maxwell later showed to be perfectly correct.

When Faraday was eventually appointed Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution, he was offered a knighthood. He turned it down, citing his religious beliefs. Albert Einstein kept a portrait of Faraday on his study wall alongside Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell. Physicist Ernest Rutherford said there was no honour too great to pay to his memory. The man who had spent his teenage years sewing pages together had, without a university, without a degree, and without the language of advanced mathematics, built the intellectual foundations of the electrical age. Every time you switch on a light, start a car engine, or charge a phone, you are using something that traces directly back to a self-educated blacksmith’s son from south London who read every book that passed through his hands.