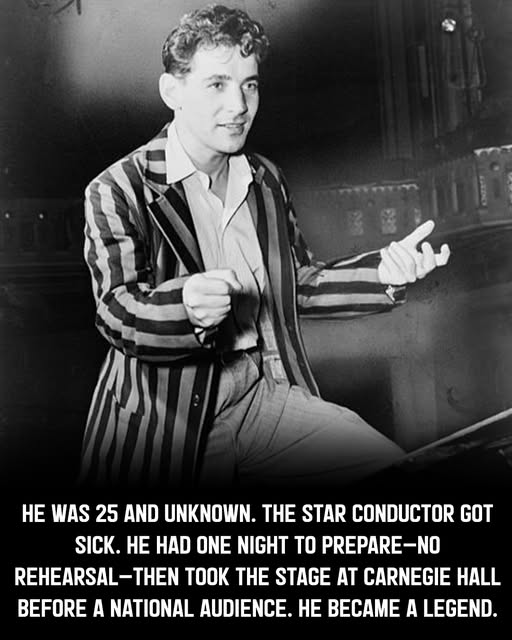

He was 25, an assistant conductor nobody knew. The star conductor got sick. He had one night to prepare—no rehearsal—then walked onto Carnegie Hall’s stage in front of a national radio audience.

November 13, 1943. Saturday evening. Leonard Bernstein was at home in New York when his phone rang. The voice on the other end belonged to someone from the New York Philharmonic, and they had news that would change his life.

Bruno Walter—one of the most celebrated conductors in the world—had fallen ill with the flu. He couldn’t conduct tomorrow’s concert at Carnegie Hall. The concert was sold out. It would be broadcast live on CBS Radio to millions of listeners across America.

They needed a replacement. Immediately.

Leonard Bernstein was 25 years old. He’d been appointed assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic just a few months earlier—a promising position, but essentially a backup role. He attended rehearsals, studied scores, and waited for opportunities that rarely came.

Now one had arrived. With less than 24 hours’ notice.

Most conductors would panic. The program was demanding: Schumann’s Manfred Overture, a difficult contemporary work by Miklós Rózsa, Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote, and Wagner’s Prelude to Die Meistersinger. Complex pieces requiring precise communication between conductor and orchestra.

And Bernstein wouldn’t get a single rehearsal.

He’d have to walk onto that stage cold, in front of a packed Carnegie Hall audience and a national radio broadcast, and conduct one of the world’s greatest orchestras through a program he’d never rehearsed with them.

He said yes.

That night, Bernstein barely slept. He pored over the scores, visualizing every tempo change, every entrance, every dynamic shift. He’d studied these works before—he had a photographic memory for music—but studying and conducting are different things entirely.

Sunday, November 14, 1943. Afternoon. Bernstein arrived at Carnegie Hall. No time for a full rehearsal. No time to work out details with the orchestra. Just a brief sound check, a few words with the musicians, and then—showtime.

At 3:00 PM, Leonard Bernstein walked onto the stage of Carnegie Hall.

The audience had come to hear Bruno Walter, a legendary conductor who’d worked with Mahler himself. Instead, they saw a 25-year-old kid they’d never heard of.

Bernstein raised his baton.

What happened next became legend.

From the opening bars of Schumann’s Manfred Overture, it was clear something special was happening. Bernstein didn’t just conduct—he embodied the music. He leaped, twisted, swayed. His gestures were huge, theatrical, passionate. Some conductors are technical. Some are precise. Bernstein was fire.

The orchestra responded. Without rehearsal, they followed his energy, his vision, his interpretation. The Rózsa was thrilling. The Strauss was nuanced. The Wagner surged with power.

When the final note of Die Meistersinger faded, there was a moment of stunned silence.

Then the audience exploded.

Applause thundered through Carnegie Hall. People stood. They cheered. They’d witnessed something extraordinary—not just a good performance, but the arrival of a major talent.

Backstage, Bernstein was mobbed. Musicians congratulated him. Audience members pushed past ushers to shake his hand. The phone lines at CBS were jammed with listeners calling to ask: Who is this guy?

The next morning, The New York Times ran the story prominently. The headline captured what everyone was thinking: a young, unknown conductor had pulled off the impossible. By Monday afternoon, Leonard Bernstein was famous.

Artur Rodzinski, the Philharmonic’s music director who’d hired Bernstein as his assistant, later said he knew immediately that November 14th would be remembered as the day Leonard Bernstein became Leonard Bernstein.

He was right.

The phone calls started immediately. Guest conducting offers poured in. Recording contracts. Commissions. Suddenly, every major orchestra in America wanted this 25-year-old who’d conquered Carnegie Hall with no rehearsal.

But November 14, 1943 wasn’t just about one great performance.

It revealed something essential about Leonard Bernstein: he was fearless.

Most conductors would have been paralyzed by the circumstances. No rehearsal? National broadcast? Substituting for a legend? The pressure alone would crush most people.

Bernstein thrived on it. The impossible odds didn’t scare him—they ignited him.

Over the next 47 years, Leonard Bernstein became one of the most important musicians of the 20th century. He composed West Side Story, Candide, and symphonies that are still performed worldwide. He became music director of the New York Philharmonic—the first American-born conductor to hold that position. He taught generations of musicians. He brought classical music to millions through his televised Young People’s Concerts.

But it all started with one phone call on a Saturday night and one impossible Sunday afternoon.

Leonard Bernstein’s story reminds us that greatness often arrives without warning. You don’t get to choose when your moment comes. You don’t get time to prepare perfectly. The opportunity appears, and you either rise to meet it or watch it pass.

Bernstein rose.

He was 25 years old, an assistant conductor with no rehearsal, facing the most important performance of his young life. He could have played it safe, followed the basics, just gotten through it.

Instead, he conducted like his entire future depended on it.

Because it did.