What you put your attention on, you manifest! Even in the animal kingdom let alone with humans! Of course the common denominator is a spirit that animates each.

Tom's Blog on Life and Livingness

What you put your attention on, you manifest! Even in the animal kingdom let alone with humans! Of course the common denominator is a spirit that animates each.

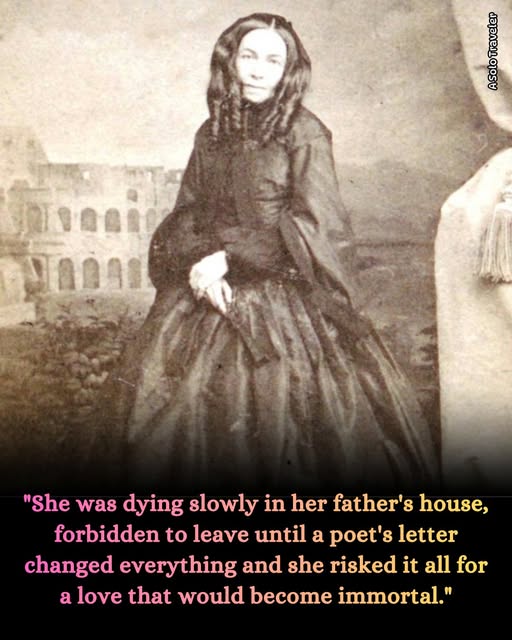

She was dying slowly in her father’s house, forbidden to leave—until a poet’s letter changed everything and she risked it all for a love that would become immortal.

Elizabeth Barrett was born in 1806 into wealth built on Jamaican sugar plantations. She was brilliant from the start—reading Homer in Greek at eight, writing epic poetry at twelve. Her father privately published her first work, “The Battle of Marathon,” when most girls her age were learning needlepoint.

Then her body began to fail.

A spinal injury. Lung disease. Pain so severe she could barely move. Doctors prescribed opium—laudanum—and she became dependent on it just to function. For years, she lived as a semi-invalid in her father’s London townhouse, confined to darkened rooms, watching life happen outside her window.

But her mind never stopped burning.

She wrote. Obsessively. Furiously. By the 1840s, Elizabeth Barrett was one of the most celebrated poets in England. Her 1844 collection “Poems” was a sensation. Critics compared her to Shakespeare. She was considered for Poet Laureate when Wordsworth died.

And then, in January 1845, she received a letter that would change everything.

“I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett…”

Robert Browning. A younger poet, six years her junior, writing to tell her that her words had moved him beyond measure. She wrote back. He replied. And suddenly, these two people who’d never met were pouring their souls onto paper.

For months, they only knew each other through letters. When they finally met in person in May 1845, something extraordinary happened. Robert saw past the invalid. Past the opium. Past the woman everyone had written off as too sick, too fragile, too ruined for real life.

He saw her.

And he wanted to marry her.

There was one massive problem: her father.

Edward Barrett was a tyrant wrapped in Victorian propriety. He’d forbidden any of his twelve children from marrying. Not for religious reasons. Not for financial ones. Simply because he wanted total control. Any child who married would be disowned completely.

Elizabeth was 40 years old. Sick. Dependent on opium. Living under her father’s roof and his rules. Most women in her position would have accepted their fate.

Elizabeth Barrett was not most women.

On September 12, 1846, she walked out of her father’s house, married Robert Browning in secret, and fled to Italy. She was 40. He was 34. Her father never spoke to her again.

And then? She came alive.

The sunshine of Florence. The freedom of her own life. The love of a man who saw her as an equal. Elizabeth flourished. Her health improved. She even had a son at 43—something doctors had said was impossible.

And she wrote the most famous love poems in the English language.

“Sonnets from the Portuguese”—Robert’s pet name for her—captured what it felt like to be truly seen, truly loved, truly free. Sonnet 43 opens with words that still make hearts stop:

“How do I love thee? Let me count the ways…”

But Elizabeth wasn’t just writing love poems.

She was furious about the world. And she used her poetry as a weapon.

“The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” confronted the horror of slavery with brutal honesty—shocking for a white Victorian woman. “The Cry of the Children” exposed child labor conditions so graphically that it helped change British law. “Aurora Leigh,” her novel in verse, argued that women deserved independence, education, and creative lives of their own.

She wrote about Italian independence. About corrupt power. About women trapped by society’s expectations. She didn’t just observe injustice—she attacked it.

Critics were scandalized. Proper Victorian ladies weren’t supposed to write about slavery, politics, or—God forbid—women’s desire for autonomy. Elizabeth didn’t care. She’d already defied the biggest authority in her life. She wasn’t about to be silenced now.

For fifteen years, she lived in Florence with Robert, writing, loving, raising their son, championing causes that mattered. She was happy. Free. Fully alive in ways she’d never been in England.

On June 29, 1861, Elizabeth died in Robert’s arms. She was 55. Her last word was “Beautiful.”

Robert never remarried. He kept her room exactly as she left it. He published her final poems and spent the rest of his life protecting her legacy.

Here’s what makes Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s story extraordinary:

She was told her life was over. That she was too sick, too old, too ruined to have love or adventure or freedom. Society had written her off. Her father had locked her away. Her body was failing.

And she said no.

She chose love over security. Freedom over approval. Life over slow death in a gilded cage.

She transformed personal pain into universal poetry. She used her privilege and platform to fight for people who had no voice. She refused to let illness, age, or society’s expectations define what was possible for her.

Every woman who’s been told she’s too sick, too old, too damaged, too much, or not enough—Elizabeth’s story is yours.

Every person who’s chosen authenticity over approval, love over fear, freedom over safety—you’re living her legacy.

She didn’t just write “How do I love thee?” She showed us: with courage, with defiance, with absolute refusal to accept a diminished life.

Your body might be fragile. Your circumstances might be limiting. The people who should support you might try to cage you instead.

But your voice? Your spirit? Your right to love and create and fight for what matters?

Those are yours. And nobody can take them unless you let them.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was dying in a darkened room until she chose to live in the full light. She wrote herself free. She loved herself whole. She made her life matter.

That’s not just history. That’s a blueprint.

Be brave enough to walk away from what’s killing you, even if it looks like safety. Love fiercely, even if it seems impossible. Use your voice, even if it makes people uncomfortable.

Because the world will always have opinions about what you should be, what you can do, who you’re allowed to love.

But you get to decide who you actually are.

Elizabeth did. And her words still echo across centuries: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways…”

All of them. Every single one. Without apology.

That’s not just poetry. That’s freedom.

A very inspiring and therapeutic chill pill.

Click to view the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=auSo1MyWf8g

Never thought of myself as a Maude! But it is a great idea! I’d like to seeit become widespread. Pass it along.

When an Amish woman has a new baby, often times a young Amish girl (about 15 or 16) will be sent to her home to help take care of the house, cook meals, and watch the other young children so the mother can spend time with her new baby. This might be a niece, or cousin or a girl in the same church district. The Maude might stay overnight for a week and then make day trips for another week or two. This is done as a gift to the new mother to allow her that time to rest and bond with her newborn. It also helps the young woman gain valuable skills in taking care of a family.

Now that’s an amazing act of kindness!

Susan Hougelman

Simple Life in New Wilmington PA

Chemical companies called her “hysterical” and an “unmarried spinster.” She was dying of cancer while they attacked her. Her book started the environmental movement. They tried to destroy her. She won.

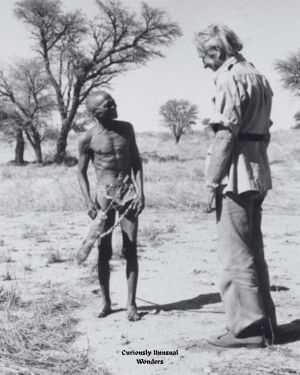

The Bushmen of the Kalahari speak of two kinds of hunger.

The Little Hunger is for food — the fire in the belly that must be fed to stay alive.

But then there is the Great Hunger.

The hunger for meaning.

The hunger that lives deeper than the stomach — in the chest, in the bones, in the quiet space behind your eyes.

It’s the ache to belong. To matter. To know why you are here.

Laurens van der Post, the man pictured here, spent years among the Bushmen — listening, learning, and trying to understand what we’ve forgotten in the modern world.

He wrote that the most dangerous thing in life isn’t sadness — it’s emptiness.

The slow, bitter erosion that comes from living without meaning.

We chase money. Status. Comfort.

We chase happiness as if it were the point.

But happiness is fleeting.

Meaning endures.

Because once you’re doing something that truly matters — something your soul recognizes as right — it doesn’t matter whether you feel good all the time.

You feel whole.

You feel connected.

You feel like you belong to something larger than yourself.

And in that belonging, even hardship becomes sacred.

This photo isn’t just a meeting between two men.

It’s a moment between two ways of being — one that remembers we are not only bodies to be fed, but spirits to be fulfilled.

Maybe that’s the real hunger we’ve been trying to feed all along.

Here are some tools to help you and those for whom you care to reveal your basic purpose in life: https://www.tomgrimshaw.com/tomsblog/?p=37862

During the filming of The Fifth Element (1997), there was a moment when the wild colors, the neon chaos, and the outrageous sci-fi humor fell away — and what remained was something unexpectedly vulnerable.

It happened while shooting one of Leeloo’s quietest scenes — the moment she looks at images of humanity’s wars and whispers, “Why… why is it worth saving?”

Milla Jovovich sat on the set, futuristic armor half-removed, exhaustion in her eyes from hours of stunts and alien language rehearsals. The crew expected another quirky take, another burst of Leeloo’s fierce innocence. Instead, she looked shaken.

Luc Besson approached her gently.

“Too intense?” he asked.

Jovovich shook her head. “No… it’s just real,” she whispered. “She’s learning what humans do to each other. And she still has to love them.”

Bruce Willis was nearby, silent. He’d spent most of the shoot being the unshakeable hero, the cool presence in a world gone mad. But in that moment, seeing Jovovich tremble, he knelt beside her and quietly said,

“Love is hard. But that’s why it matters.”

They rolled. Leeloo’s tears weren’t movie tears — they came slow, heavy, honest. Willis didn’t “act” opposite her; he just listened, his expression softening, the bravado gone.

Crew members later said it was the most human moment in a film filled with explosions, opera battles, and floating taxis.

When the take ended, Jovovich exhaled shakily and murmured,

“Saving the world isn’t the hard part. Believing it deserves to be saved — that’s the fight.”

Willis smiled, gentle — not as Korben Dallas, not as the action star, but as a man who understood tired hope.

“We save each other. One moment at a time.”

That day, The Fifth Element wasn’t wild sci-fi or comic-book spectacle.

It became a story about fragile goodness, about choosing love in a world that often forgets it — and about how sometimes the bravest thing a hero can do… is believe in humanity anyway.

Discover the revolutionary approach that transformed British Cycling from a century of mediocrity into world champions.

Click to view the video: https://www.flixxy.com/the-1-percent-rule-how-tiny-improvements-create-massive-success.htm