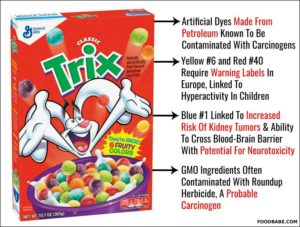

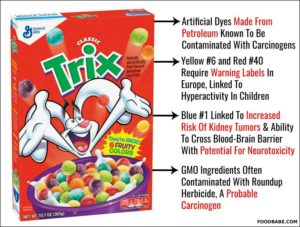

Removing them from his diet made a big difference to our 2 year old as far back as the early 1980s!

https://foodbabe.com/2017/09/28/marketing-artificial-color-children-illegal-amazing-story/

Tom's Blog on Life and Livingness

Removing them from his diet made a big difference to our 2 year old as far back as the early 1980s!

https://foodbabe.com/2017/09/28/marketing-artificial-color-children-illegal-amazing-story/

Telling it like it is!

http://careygillam.com/book

The latest trend in smoking has been E-cigarettes. They have been promoted as a much safer alternative to smoking regular cigarettes. But of course, there’s the old saying that starts out, “if it’s too good to be true…”

It turns out the Harvard School of Public Health decided to do a study on E-cigarettes and the results are startling. It looks as if they may not pose the traditional cigarette threat, but they pose a different one altogether.

Diacetyl is a flavoring chemical used in E-cigs which are linked to cases of severe respiratory disease, most notably the incurable condition called “Popcorn Lung.” This condition was first noticed in workers in microwave popcorn processing facilities who inhaled the artificial butter flavoring. The disease is totally debilitating and irreversible. It’s a respiratory disease which causes scarring in tiny air sacs in the lungs. This leads to shortness of breath and excessive coughing.

http://healthyfoodtreatments.com/e-cigarettes-cause-a-horrible-incurable-disease-called-popcorn-lung/

Someone recomended to me at the Mind Body Spirit in Sydney that I should check out the Medical Medium. Seems Anthony William and I share a view on which foods we should be consuming more.

http://www.collective-evolution.com/2017/10/30/what-your-brain-really-wants-when-you-crave-dairy-junk-food-caffeine-according-to-the-medical-medium/

About Wakefield.

You haven’t kept up with the latest on his colleague being cleared? But because you seem to cling to the idea that he was a fraud, you refuse to look at the panel who can’t refute Andrew Wakefields findings???. His finding have also been vindicated by other studies done by teams of specialists, one of them Venezuela university.

New Investigation Defends Wakefield’s Lancet Study

At the heart of the Wakefield controversy has been whether or not the children in the study were, in fact, diagnosed with non-specific colitis, or if that information had been fabricated — allegations that were largely initiated by investigative journalist Brian Deer.

Writing in the BMJ, research microbiologist David Lewis, of the National Whistleblowers Center, explains that he reviewed histopathological grading sheets by two of Dr. Wakefield’s coauthors, pathologists Amar Dhillon and Andrew Anthony, and concluded there was no fraud committed by Dr. Wakefield:

“As a research microbiologist involved with the collection and examination of colonic biopsy samples, I do not believe that Dr. Wakefield intentionally misinterpreted the grading sheets as evidence of “non-specific colitis.” Dhillon indicated “non-specific” in a box associated, in some cases, with other forms of colitis. In addition, if Anthony’s grading sheets are similar to ones he completed for the Lancet article, they suggest that he diagnosed “colitis” in a number of the children.”

In a press release, Lewis continued:

“The grading sheets and other evidence in Wakefield’s files clearly show that it is unreasonable to conclude, based on a comparison of the histological records, that Andrew Wakefield ’faked’ a link between the MMR vaccine and autism.

Now that these records have seen the light of day, it is time for others to stop using them for this purpose as well. False allegations of research misconduct can destroy the careers of even the most accomplished and reputable scientists overnight. It may take years for them to prove their innocence; and even then the damages are often irreparable. In cases where mistakes are made, every effort should be taken to fully restore the reputations and careers of scientists who are falsely accused of research misconduct.”

And, because there have been informed people all through the ages, from 1900…

http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/162135861?q&versionId=176701567

This was the recommendation from a friend on Facebook…

He toured Australia in the mid eighties, I bought his books back then raised my son’s now 35, 31 and 28 using his common sense book as a reference.

Brilliant book that every parent should have.

He called vaccinations The Medical Time Bomb and he’s not wrong….He was highly qualified and died way too young and way too healthy for my mind…..

This book I recommend to every parent.

By the way my son’s are all extremely healthy, got all childhood illnesses and are healthier because they did….immune systems are strong and their health and vitality is the envy of all their peers…

https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&an=Robert+Mendelsohn&tn=How+to+raise+a+healthy+child+&kn&isbn&sortby=93