By Matt Shumer • Feb 9, 2026

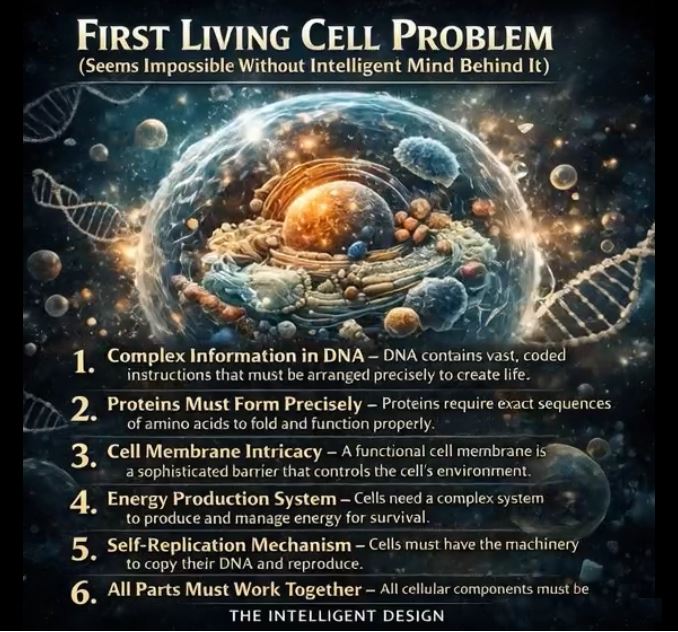

First Living Cell Problem

Charles Boycott

In 1880, a wealthy British land agent named Charles Boycott lived on a sprawling estate in County Mayo, Ireland. He was an uncompromising man who managed lands for an absentee lord.

A terrible harvest had left the local farmers starving and unable to pay their full rent. They didn’t ask for a handout. They simply asked for a 25 percent reduction to survive the winter.

But Charles Boycott was not a man of compromise. He refused their pleas and began the process of eviction to throw families out of their homes.

He expected the peasants to fold under his authority. He expected them to fear the law he represented.

But the people of Ireland had found a new champion in the Land League. Their leader, Charles Parnell, had proposed a different kind of warfare.

Instead of violence, Parnell suggested a policy of total social isolation. He told the people to treat an unfair landlord like a leper of old.

When Boycott tried to hire local workers to harvest his crops, nobody showed up. The fields sat heavy with overripe grain, rotting in the Irish rain.

He walked into the local shops to buy supplies, but the shopkeepers turned their backs. They would not take his gold.

He sent for his mail, but the postman refused to deliver it. His servants walked out of his house without a word, leaving him to cook his own meals.

He saw their resolve. He saw their silence. He saw their power.

But the British government stepped in to assist him. They sent 50 orange-men from the north and 1,000 soldiers to protect them while they harvested the crops.

It cost the government over 10,000 pounds to harvest a crop worth only 350 pounds. The victory was hollow.

Charles Boycott was a broken man. By December of that year, he fled Ireland in a carriage protected by a military escort.

His name was no longer just a name. It had become a verb that described the most powerful non-violent weapon in history.

Today, we still use his name whenever a community stands together to stop unfair practices. Collective action remains the strongest check on unbridled power.

Sources: Britannica / National Library of Ireland / History Channel

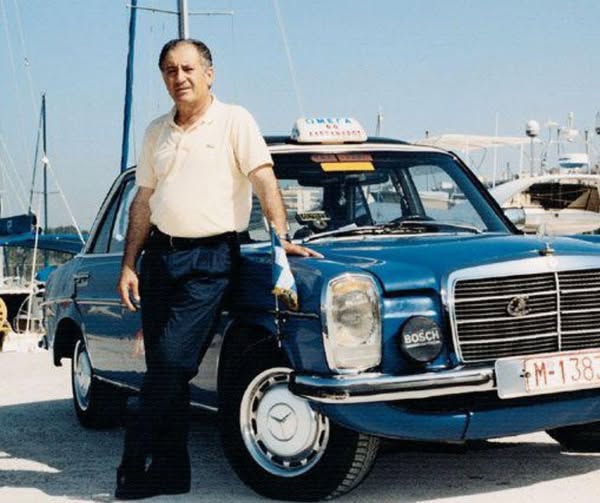

Gregorios Sachinidis’ Mercedes

He drove the same taxi for 23 years, performing every repair himself. When the odometer passed 4.6 million kilometers, Mercedes-Benz bought the car and put it in their museum.

Thessaloniki, Greece. 1976.

Gregorios Sachinidis, a taxi driver, purchased a brand-new Mercedes-Benz 240D. It was silver-gray, diesel-powered, built with the solid German engineering Mercedes was famous for.

For most people, a new car is exciting for a few years, then becomes just transportation. Eventually, it gets replaced.

Gregorios had a different plan.

He was going to drive this car until it couldn’t drive anymore. And he was going to take care of it so well that “couldn’t drive anymore” would take decades to arrive.

Every morning, Gregorios would inspect his Mercedes before starting work. He’d check fluid levels, tire pressure, listen to the engine. He treated the car not like a tool, but like a partner.

As a taxi driver in Thessaloniki—Greece’s second-largest city—Gregorios drove constantly. Airport runs. Long-distance fares to other cities. Daily commutes through heavy traffic. The car ran nearly 24 hours a day, often driven by Gregorios in marathon shifts.

Most taxis are destroyed by this kind of use. The constant stop-and-start, the heavy loads, the endless hours—it wears vehicles down quickly. Most taxi fleets retire cars after 300,000-500,000 kilometers.

Gregorios passed 500,000 kilometers in his first few years.

And kept going.

The secret wasn’t just the Mercedes engineering—though the 240D was legendary for durability. The secret was Gregorios himself.

He was both driver and mechanic. Every maintenance task, every repair, every adjustment—he did it himself. He didn’t trust anyone else with his car.

Oil changes? Done precisely on schedule, never delayed.

Brake pads? Replaced before they wore dangerously thin.

Engine adjustments? Performed with meticulous attention.

Gregorios kept detailed records of every service, every part replacement, every modification. He knew his Mercedes better than most people know their own homes.

When something made an unusual sound, he’d diagnose it immediately. A slight vibration? He’d investigate. A minor leak? Fixed before it became major.

This wasn’t obsession. It was respect—understanding that a machine given proper care will give years of reliable service.

The kilometers accumulated: 1 million. 2 million. 3 million.

Other taxi drivers watched in amazement. Mechanics who serviced the car were astounded. “This engine should have been rebuilt twice by now,” they’d say. “How is it still running?”

Gregorios would smile. “You take care of it, it takes care of you.”

By the mid-1990s, Gregorios’s Mercedes had passed 4 million kilometers—a distance equivalent to circling Earth 100 times at the equator, or driving to the moon and back more than five times.

The car had become legendary in Thessaloniki. Passengers would specifically request “the taxi driver with the million-kilometer Mercedes.” Journalists wrote articles. Car enthusiasts made pilgrimages to see it.

But Gregorios wasn’t interested in fame. He was interested in work. Every day, he’d climb into his Mercedes, turn the key, and the engine would start—reliable as sunrise.

The seats were worn from thousands of passengers. The steering wheel bore the smooth indentations of his hands. The dashboard had faded from decades of Greek sunshine. But the engine? The transmission? The mechanical heart of the car?

Still strong.

By 1999, the odometer showed over 4.6 million kilometers.

That’s when Mercedes-Benz heard about Gregorios Sachinidis.

Company representatives traveled to Thessaloniki to verify the claim. They inspected the car thoroughly, checked maintenance records, interviewed Gregorios.

Everything was authentic. The odometer hadn’t been tampered with. The engine was original (though rebuilt components had been replaced as needed). This was genuinely a 1976 Mercedes-Benz 240D that had been driven over 4.6 million kilometers—and was still running.

Mercedes-Benz made Gregorios an offer: they wanted to purchase the car for their museum in Stuttgart, Germany.

It would be displayed as a testament to Mercedes engineering and to the importance of proper maintenance—a real-world example of what was possible with quality manufacturing and dedicated care.

Gregorios accepted.

Saying goodbye to the car must have been bittersweet. For 23 years, that Mercedes had been his livelihood, his companion, his daily reality. He’d spent more time in that car than in his own home.

But he also understood the significance. His car would inspire mechanics, engineers, and drivers worldwide. It would prove that with proper care, machines can serve far beyond their expected lifespan.

Today, the 1976 Mercedes-Benz 240D sits in the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart. A plaque explains its extraordinary history: over 4.6 million kilometers driven by a single owner, maintained meticulously, a world record holder.

Visitors from around the globe come to see it—not because it’s exotic or beautiful, but because it represents something profound: the relationship between human care and mechanical reliability.

Gregorios Sachinidis proved several things with his faithful Mercedes:

First, quality engineering matters. The Mercedes-Benz 240D was built to last, with robust components and thoughtful design. But engineering alone wasn’t enough.

Second, maintenance is everything. Even the best-built car will fail without proper care. Gregorios’s meticulous attention to every detail—oil changes, brake inspections, engine adjustments—extended the car’s life far beyond normal expectations.

Third, respect for tools matters. Gregorios didn’t treat his taxi as disposable. He treated it as a partner in his livelihood, worthy of care and attention.

Fourth, expertise counts. Gregorios wasn’t just a driver—he was a skilled mechanic who understood his vehicle intimately. That knowledge allowed him to prevent problems before they became catastrophic.

Finally, patience and consistency win. There were no shortcuts. Just 23 years of daily diligence, small careful actions repeated thousands of times.

The story resonates because it contradicts our disposable culture. We’re taught that things wear out, break down, need replacing. Planned obsolescence is built into many products.

Gregorios’s Mercedes proves that with care, quality, and dedication, machines can serve far longer than manufacturers often promise.

The 240D wasn’t designed to last 4.6 million kilometers. But it did—because someone refused to accept that “good enough” was sufficient.

Other taxi drivers have tried to match Gregorios’s record. A few have come close. But most give up or retire before reaching even 2 million kilometers. The physical and mental dedication required is extraordinary.

You can’t skip maintenance. You can’t ignore warning signs. You can’t get lazy about care. One missed oil change, one ignored repair, and the streak ends.

Gregorios maintained that discipline for 23 years.

His story inspired Mercedes-Benz to emphasize durability in their marketing. “Built to last” became more than a slogan—Gregorios’s taxi was proof.

It also inspired mechanics and car enthusiasts worldwide. Online forums dedicated to high-mileage vehicles cite Gregorios as an example of what’s possible. His maintenance philosophy—preventive care, attention to detail, respect for machinery—is taught in technical schools.

Gregorios Sachinidis wasn’t famous. Wasn’t wealthy. Wasn’t particularly remarkable except for one thing:

He took extraordinary care of an ordinary car, and in doing so, achieved something extraordinary.

4.6 million kilometers.

23 years.

One man.

One Mercedes.

And the simple, powerful lesson that when you take care of things properly, they take care of you.

The silver-gray 1976 Mercedes-Benz 240D sits in Stuttgart today, a monument not to luxury or speed or beauty.

But to diligence. To care. To the quiet pride of work done well, day after day, for decades.

Gregorios eventually retired, bought a new taxi, and continued working.

But he never forgot his faithful Mercedes. And neither did the world.

Because sometimes, the most extraordinary achievements don’t come from dramatic moments.

They come from showing up every day, doing the work carefully, and refusing to take shortcuts.

For 4.6 million kilometers.

One kilometer at a time.

Grok says of the story:

Yes, the story is true, with a few minor inaccuracies or embellishments in the version you shared compared to verified sources (including Mercedes-Benz’s own official archives).

The core facts check out: Gregorios Sachinidis (sometimes spelled Grigorios or variations like Sachinides/Sahinidis) was a taxi driver in Thessaloniki, Greece. He acquired a 1976 Mercedes-Benz 240D (W115 series, diesel) in 1981—it was already used, with about 220,000 km on the clock (not brand-new as the story claims). He drove it intensively as a taxi for roughly 23 years until 2004, racking up a total of 4.6 million kilometers (about 2.85 million miles). This made it the highest-mileage Mercedes-Benz on record at the time (and possibly still, based on recent references).

He performed meticulous maintenance himself, which was key to the longevity—regular oil changes, preventive repairs, and treating the car like a partner, aligning perfectly with the inspirational tone in the post.

Mercedes-Benz verified the odometer and records, confirmed authenticity (original engine block, though with normal rebuilds/replacements of wear parts), and acquired the car for their museum in Stuttgart, Germany, where it’s displayed as an example of durability and proper care. In exchange, they provided him with a new vehicle (often reported as a C-Class diesel).

Key differences from the story you posted:

He didn’t buy it brand-new in 1976 in Thessaloniki; he bought it used in Germany in 1981 and brought it to Greece.

The handover was in 2004 (not 1999), and it was more of a donation/transfer with a new car as a reward than a straight “purchase” (though sources describe it variably as Mercedes “buying” or “acquiring” it).

The dramatic “when the odometer passed 4.6 million” moment and company reps rushing to Thessaloniki to verify is dramatized, but the verification and acquisition did happen.

It’s not the absolute world record for any car (some Volvos and others have higher verified mileages), but it was the highest for a Mercedes and one of the highest overall for a single-owner vehicle.

This has been documented in:

Mercedes-Benz’s official public archive (they describe it as the highest known mileage for their brand, highlighting the W115’s longevity).

Greek media (e.g., Greek City Times articles from 2021 and 2025).

Automotive forums, enthusiast sites, and news outlets over the years (e.g., Team-BHP, Vintage Everyday, Supercar Blondie).

The inspirational lessons about maintenance, respect for machinery, and quality engineering hold up—it’s a genuine example Mercedes themselves have promoted.

So, while the narrative is a bit polished and motivational (as these viral stories often are), the events really happened.

On Taking Responsibility

A Boston College historian spent 30 years studying why great societies collapse — and she found 1 pattern that exposed the 3 words people always say right before everything falls apart.

Her name is Heather Cox Richardson. She is a history professor at Boston College. She has spent over three decades studying the rise and fall of American democracy. While most of us doomscroll through headlines until our stomachs turn, she does something different. She opens dusty archives. She reads forgotten letters. She traces the invisible cracks that appeared long before any civilization crumbled.

And after studying centuries of history, she noticed something chilling. The same three words appear again and again, spoken by ordinary people, just before disaster strikes.

“Someone will fix it.”

Let me explain what she means.

Picture an ordinary American family in 1859. A husband and wife sitting at a kitchen table. They have noticed things changing around them. The newspapers are angrier. Neighbors who once waved at each other now cross the street to avoid conversation. Political arguments at church gatherings have turned bitter and personal.

They feel the tension. They sense something is wrong. But they tell themselves the same thing millions of others are telling themselves at the very same moment.

Someone will fix it. The leaders will sort this out. The system is strong enough to hold.

Two years later, 620,000 Americans were dead in the bloodiest war the nation had ever seen.

To us, reading history books, the Civil War feels like it was always going to happen. We see the dates. We follow the timeline. We watch the dominoes fall in a sequence that seems obvious and unavoidable.

But to the people living through those years, nothing felt inevitable. They were just regular folks trying to get through their days. They believed things would work out because they had always worked out before.

Richardson has studied this pattern across American history, and she says it repeats with heartbreaking consistency. Good people see warning signs. They feel the ground shifting. But they convince themselves that someone else will step in. That the system will correct itself. That the fever will break on its own.

And by the time they realize no one is coming to save them, the window to act has already narrowed.

This is the heartbreak of studying history. You can see exactly where the exit ramps were. You can see the moments when one brave conversation, one different choice, one act of courage could have changed everything. You want to reach through time and shake people awake.

But here is where Richardson’s message shifts from warning to something powerful.

Those families in 1859 cannot go back. Their story is written. The ink is dry. The pages are sealed.

But ours are not.

We are living in an unfinished chapter. The pages ahead of us are completely blank. And unlike those families in 1859, we have something extraordinary on our side. We have their story. We know what happens when people stay silent. We know what happens when citizens assume the system will protect itself. We have centuries of hard evidence showing us exactly what the warning signs look like.

That knowledge, purchased at a staggering price by the generations who came before us, is our greatest advantage.

Richardson reminds us that civilizations almost never collapse in one dramatic moment. There is no single explosion. No single villain. No single day when everything falls apart. Instead, they erode. Slowly. Quietly. They die by a thousand small surrenders. They fade when exhausted people decide the fight is no longer worth having. They crumble when citizens forget one critical truth.

The system is not something separate from us. The system is us.

But Richardson also teaches the opposite lesson. Because history is not only a record of failure. It is also a record of impossible victories.

The women who fought for the right to vote had no guarantee of success. They marched for over 70 years. They were jailed. They were beaten. They were mocked in newspapers and dismissed by the men who held power. Many of them died without ever casting a single ballot. But they kept showing up. And they changed the world.

The civil rights activists of the 1950s and 1960s faced firehoses, attack dogs, bombings, and assassinations. Every single day, they woke up not knowing if their movement would survive. The outcome was never certain. Victory was never promised. But ordinary people, bone-tired and deeply afraid, chose to stand anyway.

Those movements did not succeed because the odds were in their favor. They succeeded because enough people refused to sit down when everything inside them wanted to quit.

And here is what Richardson wants us to carry with us today.

We are standing at our own crossroads right now. The chapter ahead is unwritten. That blankness feels terrifying. It keeps us awake at night. It makes us wonder if the future is already decided.

But it is not.

Every single day holds choices. How we talk to the person who disagrees with us. Whether we engage with our community or retreat behind locked doors. Whether we let fear push us toward silence or whether we find the courage to speak. Whether we surrender to the idea that nothing can be done or whether we pick up the pen and start writing something different.

Heather Cox Richardson has spent her life studying the ghosts of history. She knows their stories like old friends. She has traced their mistakes with sorrow and their victories with admiration.

But she does not live in the past. She lives in the fierce, stubborn hope of this present moment. Because she understands something most of us forget.

Inevitability only applies to what has already happened.

Tomorrow is still wet cement. We can still leave our handprints in it. We can still shape it into something worth passing down.

History is not a prison sentence. It is a map drawn by those who walked before us, showing us both the dead ends and the open roads.

The people who understand that map best are the ones standing in front of us right now, saying the same thing.

We still have time. But time does not wait for people who keep saying someone else will fix it.

The question was never whether we could change the story. The question has always been whether we will.

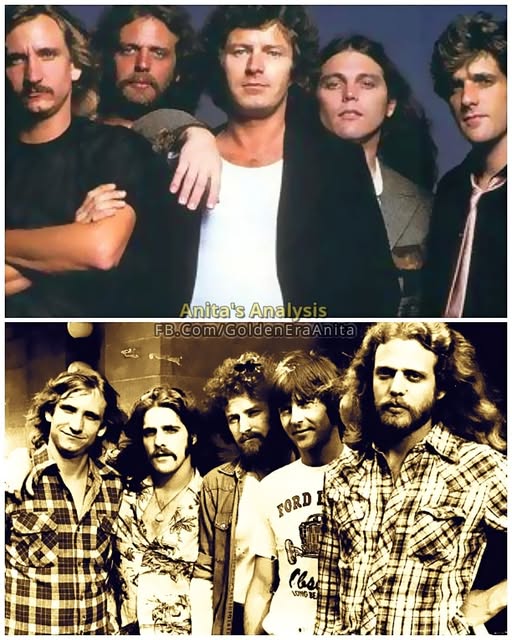

The Eagles – Hotel California

Doing the right thing is very rarely the wrong thing to do.

Weeks into recording “Hotel California” from the album “Hotel California” released in 1976, the Eagles faced a brutal realization. The master take sat in the wrong key for Don Henley’s vocal range. After investing countless studio hours polishing the arrangement, layering guitars, and tightening harmonies, the band made a costly decision. They scrapped the entire version and started again from the ground up.

The foundation of the track came from guitarist Don Felder, who had assembled a series of demo ideas on a 12 string guitar. When the band began shaping it in the studio, the instrumental track felt powerful and expansive. Henley pushed his voice to meet the melody line, but as sessions progressed, strain became obvious. The key demanded sustained high notes that could not hold up across multiple takes. Recording an album at that level of intensity meant repeating vocals for precision. A key that felt barely manageable on day one became punishing after weeks.

Producer Bill Szymczyk recognized the issue while listening to playback. Technically, nothing was wrong with the arrangement. The rhythm section locked in tightly. Joe Walsh and Don Felder were refining what would become one of the most recognizable dual guitar sequences in rock history. Randy Meisner had already departed the band by that time, leaving Timothy B. Schmit to handle bass duties during the later touring era, though the album sessions still reflected the earlier lineup transition period. The problem centered on sustainability. Henley’s voice carried emotional weight in “Desperado” from 1973 and “One of These Nights” from 1975, yet this melody required a slightly lower placement to preserve strength and tone.

Lowering the key meant dismantling everything. Guitar voicings changed. Chord shapes shifted. Harmonic textures had to be rebuilt. Tape in the mid 1970s was expensive, and studio time in Los Angeles did not come cheap. The band had already invested heavily in making “Hotel California” the defining statement of their career. Letting go of a completed version required discipline few artists demonstrate at that stage of success.

Henley later acknowledged in interviews that he preferred singing within a range that allowed intensity without damage. Touring schedules added pressure. A recording key that barely worked in the studio could collapse under the stress of nightly concerts. The Eagles had learned from earlier albums like “On the Border” released in 1974 that studio precision must translate to the stage. If the song became a single, which it eventually did in 1977, it needed to hold up in arenas.

The restart process sharpened the band’s focus. Instead of treating the setback as failure, they approached it as refinement. Joe Walsh, who had joined prior to the album’s release, contributed textural guitar work that deepened the atmosphere. Felder reworked his parts to match the adjusted pitch. Henley delivered vocals with greater control once the melody sat comfortably in his range. What had begun as a technical obstacle transformed into a defining strength.

There was also a psychological element. By 1976, the Eagles were no longer a developing act. They were expected to produce a landmark record. Pressure mounted from both the label and the industry. Starting over signaled that they valued longevity over convenience. Sacrificing weeks of labor showed a commitment to quality that shaped the final sound.

The finished recording of “Hotel California” achieved commercial and critical success, winning the Grammy Award for Record of the Year in 1978. Listeners never heard the discarded version. They heard a performance balanced between power and restraint. That balance existed because the band confronted a mistake early enough to correct it.

Choosing to reset the key preserved Henley’s vocal authority and secured the song’s durability for decades of live performances, proving that technical humility can define artistic permanence.

Is Brain Rot Real? Researchers Warn of Emerging Risks Tied to Short-Form Video

Heavy short-form video use trains your brain to favor speed and novelty, which weakens sustained focus and makes everyday tasks feel harder to finish.

Attention loss linked to scrolling reflects learned brain adaptation, not a lack of intelligence, motivation, or discipline.

Endless feeds strain self-control systems, raising stress and mental fatigue while leaving confidence and self-image largely unchanged.

Younger users and frequent daily scrollers show the strongest effects, but attention strain appears across all ages and platforms.

Source: https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2026/02/11/brain-rot-short-form-video.asp

A Single 20g Dose of Creatine Increases Cognitive Processing Speed by 24.5% Within 3.5 Hours

A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that creatine rapidly enhanced brain bioenergetics and improved cognitive performance during sleep deprivation, with effects lasting up to nine hours.

Source: https://open.substack.com/pub/petermcculloughmd/p/a-single-20g-dose-of-creatine-increases

Grain-Free Schizophrenia Cure

Zero. That is the number of researchers who have published peer-reviewed studies on diet and schizophrenia who were contacted by the journalists who called the science “unfounded.”

Large Study Shows Flu Shot Increases The Risk Of Influenza By 27% – Yet 46% of Americans Still Go And Get Their Flu Shot A Year Later

As of January 31, 2026, approximately 46.0% of adults and 46.4% of children aged 6 months to 17 years reported having received a flu vaccination during the 2025-2026 season, showing a slight increase compared to the previous season.

A large Cleveland Clinic Study the year prior showed that the Flu Shot INCREASED THE RISK OF GETTING THE FLU BY 27%.

Finish reading: https://open.substack.com/pub/anamihalceamdphd/p/large-study-shows-flu-shot-increases