Covid Jabs and Increased Cancer Rates

“More young Australians – are being diagnosed with Cancers – once thought once only to affect older people”

“Cancer rates are increasing in young Australians:

“Ovarian Cancer up 30% – Breast Cancer up 50% & Bowell Cancer up 71% – other Cancers rates are increasing.”

It isn’t just Australia – its the entire Western world – now there’s detailed peer reviewed studies with huge sample numbers – proving the link between the Covid vaccines and cancer rates.

Of course Legacy Media will never ever tell you this – as they were also the ones that told you repeatedly to take the experimental jabs.

Watch video: https://x.com/BGatesIsaPyscho/status/2025852402939695407?s=20

Is Your Blood Pressure High or Not?

Ever wonder why “normal” blood pressure keeps getting lower? Each drop expands the market — turning healthy people into lifelong customers.

~1940: 100 + your age (165/90 normal for a 65 yr old)

~1970: 160/90

~2000: 140/90

~2026: Must be under 120/80, or you’re “hypertensive”

The Profit Incentive…

• Global antihypertensive market: ~$27 billion in 2025

• Lower thresholds = millions more “diagnosed” = more scripts & revenue

• Most drugs only mask symptoms (stiff arteries, inflammation, stress) while creating side effects that often require…more drugs

Common Medication Side Effects…

• Chronic cough (ACE inhibitors)

• Electrolyte imbalances, low potassium/sodium (diuretics)

• Dizziness, fatigue, headaches

• Dehydration, muscle cramps, gout flares

• Insomnia, depression, vivid nightmares

• Slow/erratic heart rate, breathing issues

• Erectile dysfunction, libido loss

• Fainting spells, orthostatic hypotension

• Kidney strain, rare but serious angioedema

• In frail elderly: overly low BP linked to HIGHER mortality risk

Natural Ways to Optimize BP (Address Root Causes)…

• Eat whole, nutrient-dense foods — prioritize animal-based proteins, organs, eggs, dairy

• Eliminate seed oils, ultra-processed foods & excess sugar

• Boost potassium & magnesium (mineral-rich salt, leafy greens, avocados, supplement 4,700mg potassium & 600+mg magnesium glycinate if needed)

• Manage stress (breathwork, nature, sleep hygiene)

• Strength training + consistent movement

• Prioritize quality sleep & circadian rhythm

• Increase Nitric Oxide thru food & supplements.

Key nuance: In adults 80+, higher BP often correlates with better survival. Aggressive lowering can be harmful.

Question the ever-lowering numbers. Your health — not Pharma’s bottom line — should come first.

Video: https://x.com/ValerieAnne1970/status/2025616578470170990?s=20

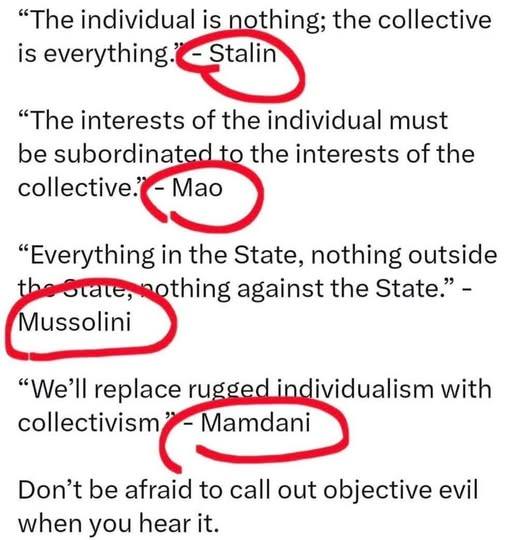

Collectivism vs Individualism

Those who fear you and wish to harm you try to make nothing of you. Keep that in mind when you look around and see who promotes what.

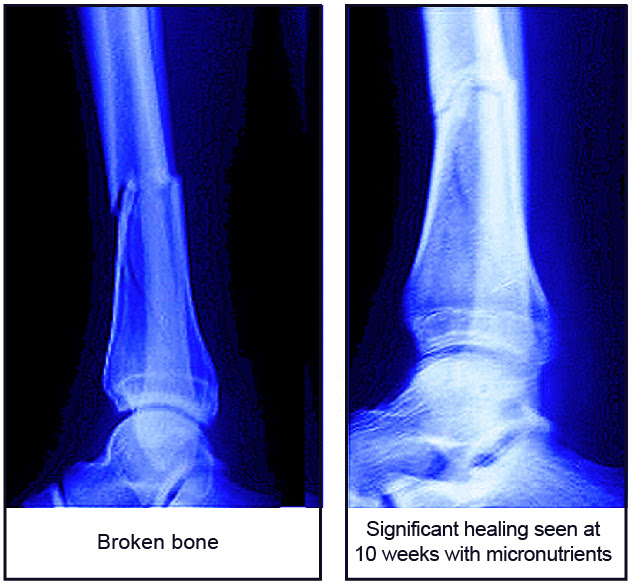

Healing bone fractures: rarely considered micronutrients

Everyone is at risk of fracturing a bone from a fall, sport activities, or a car accident and it is all the more likely to happen to people suffering from osteoporosis. Bone fractures are one of the most painful injuries and require a lengthy recovery time.

The most common bone fracture, especially in active adults and children, is a broken leg, and often involves a tibial (or shinbone) fracture. In the US, approximately 492,000 tibial fractures are reported every year resulting in close to 400,000 hospital days. The usual time for healing a tibial fracture is 12 to 16 weeks. However, this is often delayed due to a high incidence of complications requiring strong painkillers for the patient. In European countries, osteoporosis related hip fractures were reported to be 620,000 according to a 2010 report.

A common perception is that vitamin D and calcium are the only nutrients needed for healthy bones or that they aid in the fracture healing process. However, this overlooks the fact that the framework of the bone on which calcium and other minerals are deposited is made of protein – collagen. Without healthy collagen, bone cannot form and function properly. Healthy bone formation depends not only on sufficient amounts of calcium and vitamin D, but more importantly on a proper supply of vitamin C, the amino acids lysine and proline, and other collagen supporting micronutrients. Since the human body cannot produce vitamin C and lysine internally, the deficiency of these critical nutrients is very likely and can be further depleted by stress associated with a bone fracture.

In a randomized double blind placebo-controlled clinical trial* involving 131 patients with tibial shaft fracture, we evaluated the effect of supplementation with collagen building micronutrients on the fracture healing time. The ages of study participants ranged from 15 to 75. We observed that the group of patients taking essential micronutrients containing vitamin C, lysine, proline, and vitamin B6 experienced faster fracture healing. Their fractures healed in 14 weeks, while it took 3 weeks longer for the patients taking the placebo (sugar pill) to experience similar healing. In addition, in about 25% of the patients in the supplemented group the bone fractures healed in as early as 10 weeks, while this was noted in only 14% of the patients in the control group. The patients in the supplemented group also reported improvements in a general feeling of well-being.

This study shows that a frequently missing factor in bone health – healthy collagen – plays an important role in optimum healing of bone fractures. A simple supplementation with specific micronutrients could greatly reduce healing time and patient suffering as well as lessen the economic burden on patient families and the healthcare system.

Top 12 low-carb vegetable options that maximize phytonutrient absorption

- Low-carb vegetables, primarily those growing above ground like leafy greens, are foundational to a ketogenic diet, offering maximal nutrients for minimal carbohydrate impact.

- The concept of “net carbs,” which subtracts indigestible fiber from total carbohydrates, is crucial for accurately assessing a vegetable’s suitability for keto.

- Each recommended vegetable possesses a distinct phytochemical and nutritional profile, contributing specific health benefits from antioxidant protection to anti-inflammatory support.

- Cooking methods can significantly influence the retention of nutrients, with techniques like quick steaming, sautéing, and roasting often preferred to preserve vitamin content and texture.

- Historical dietary shifts highlight the modern return to valuing vegetable diversity, moving beyond mere calorie counting to an appreciation for micro-nutrient density and functional food benefits.

A dozen pillars of low-carb nutrition

The guiding principle is straightforward: vegetables that grow above ground, particularly the leafy greens, typically harbor fewer digestible carbohydrates. This stands in contrast to colorful root vegetables like carrots and sweet potatoes, which store energy as sugars and starches and must be consumed judiciously. The metric that matters here is “net carbs”—the total carbohydrates minus the fiber. Since fiber passes through the digestive system largely intact, it does not spike blood sugar, making it the critical number for keto adherents.

Examining the list reveals a roster of familiar and versatile foods, each with a compelling nutritional narrative. Spinach and kale are the titans of the leafy greens. Spinach, with a mere one gram of net carbs per serving, is a stealthy source of iron, magnesium, and vitamins A and K. Its mild flavor allows it to be incorporated into everything from morning eggs to creamy soups. Kale, slightly higher in carbs but exceptionally dense in nutrients, is rich in vitamins A, C, and K, and contains antioxidants like quercetin. Historically, kale was a European staple for centuries, valued for its hardiness; today, its resurgence is tied directly to its superfood status. For both, gentle sautéing or consuming them raw in salads helps preserve their heat-sensitive vitamin C and folate.

Cruciferous vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts form another cornerstone. They are celebrated for sulforaphane, a phytochemical with potent anti-inflammatory and potential cancer-protective properties. Broccoli and Brussels sprouts, each at about four grams of net carbs, are also excellent sources of vitamin C and folate. Cauliflower’s genius lies in its chameleon-like versatility at only two to three grams of net carbs; it can be riced, mashed, or even formed into a pizza crust. These vegetables benefit from cooking methods that avoid turning them to mush: roasting caramelizes their natural sugars, while quick steaming retains a crisp-tender texture and a greater percentage of their nutrients compared to boiling.

Then come the structural supports: asparagus, celery, zucchini, and green cabbage. Asparagus, a symbol of spring, is rich in folate and acts as a natural diuretic. It shines when grilled or quickly pan-seared. Celery, often dismissed as mere crunch, provides valuable vitamin K and apigenin, an antioxidant compound. Its historical use in medicine precedes its culinary role. Zucchini, at three grams of carbs, is the low-carb pasta alternative, easily spiralized into “zoodles” that absorb sauces beautifully. Green cabbage, a durable and historically vital food source across many cultures, is rich in vitamin C and can be fermented into sauerkraut, which adds beneficial probiotics to the gut.

Mushrooms, bell peppers, and the honorary fruit avocado round out the list with unique offerings. Mushrooms are the only item here that is not a plant but a fungus, providing B vitamins and the antioxidant mineral selenium. Their savory, umami flavor enhances any dish. Bell peppers, particularly the red varieties, are bursting with vitamin C, and their bright colors signal a high carotenoid content. The avocado is in a class by itself, providing nearly 20 vitamins and minerals and a wealth of monounsaturated fats, making it a perfect keto-friendly fat source to complement fibrous vegetables.

Maximizing the benefits from garden to table

Choosing these vegetables is only the first step. How they are prepared dictates the final nutritional payoff. Water-soluble vitamins like vitamin C and many B vitamins are vulnerable to heat and water. This makes techniques like quick sautéing in a healthy fat like coconut oil, ghee, or olive oil, or roasting at high heat, superior to prolonged boiling. Fat is not just for flavor; it aids in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K found abundantly in these vegetables. A drizzle of olive oil on roasted Brussels sprouts or a handful of avocado slices in a spinach salad is not just tasty, it is nutritionally synergistic.

The contemporary focus on these specific vegetables reflects a broader evolution in nutritional science. It is a move away from viewing food solely through the lens of macro-nutrients and toward an appreciation for the complex, synergistic effects of phytochemicals—the natural compounds that give plants their color, flavor, and protective properties. From the glucosinolates in broccoli to the anthocyanins that might give a purple hue to some cabbages, these components work in concert with vitamins and minerals to support cellular health, combat oxidative stress, and reduce inflammation.

Ultimately, building a low-carb diet around this diverse dozen is an exercise in nutritional intelligence. It is a plan that avoids monotony by offering a spectrum of textures, from the crisp snap of a raw bell pepper to the creamy heart of a roasted cauliflower. It connects modern dietary goals with the enduring wisdom of eating a wide variety of plants. For the individual committed to a low-carb path, these vegetables are far more than a permissible side dish. They are the essential, vibrant, and flavorful foundation upon which sustainable health is built.

Quote of the Day

“Constant kindness can accomplish much. As the sun makes ice melt, kindness causes misunderstanding, mistrust, and hostility to evaporate.”

Albert Schweitzer – Humanitarian (1875 – 1965)

An Encouragement To Expand Your Definition of ‘Home’

The sane and orderly of us keep a neat, tidy home, time and resources permitting. The state of the planet suggests we need to expand our definition of ‘home’ to be broader and more embracive.

Woke up early this morning thinking about our planet. Of all the things that have to be in place for optimal survival. Not about civilization, government, industry, trade and commerce or even clothing and shelter but basic level survival, like eating, and how good a job we could be doing but aren’t.

For starters, all life depends on sunshine as the basic starting block – our energy source. And some are thinking of blocking it!

Then there’s air. For centuries we have been polluting it and despite massive improvements we still have a long way to go. That’s just what we breathe. At a higher level the upper atmosphere is becoming increasingly congested with space debris that needs cleaning up.

And water. This is where quality really start to go downhill at an alarming rate. From drugs in the water that alter the gender of fish, whole, micro and nano-plastics that get into the food supply and wind up in our brain to chemicals, microfibers, industrial waste and untreated human effluent, the assault on clean, pure water is extensive and increasing. And we haven’t touched on the depleting aquifers and polluting them with fracking chemicals.

Finally, our soil. It has been said that the only thing that stands between us and extinction is 6 inches of topsoil and rain. So as soil is vitally important to preserve life, it deserves a mention. It is of and grave concern to learn that over the last 150 years we have lost 50% of the world’s topsoil.

What with long-term mono-cropping, continually farming crops without full composting, crop rotation and letting fields lie fallow, we are rapidly depleting the ability of soil to grow crops that fully nourish our bodies. And then there is the continued application of chemicals like glyphosate that kill the biodiversity in the soil.

These are all planet-wide problems so you could be forgiven for thinking, “What can I, as one person, do about them? It is too large a problem for me to affect.”

To help you take action on a personal level and give you data so you can advise others I have compiled a list of simple steps you can take, each of which will contribute to a better home for us all.

In no particular order of importance:

Sun

Oppose sun blocking experiments

Air

Don’t smoke or vape.

Buy low VOC paints/cleaners.

Use exhaust fan when cooking.

Walk or bike rather than drive short distances.

If you have a car, keep it well serviced to minimize pollution and waste.

Oppose atmospheric regulation or aerosol weather manipulation.

Water

Fix leaking taps promptly.

Install drip irrigation in your garden.

Use dishwasher and washing machine only with full loads.

Avoid microbead containing products.

Use ecofriendly detergents.

Avoid pouring fats/oils/grease, household chemicals, medications, or pharmaceuticals down drains—dispose properly via collection programs.

Filter your tap water for drinking rather than buying bottled water.

Buy natural fiber (cotton/hemp) clothes rather than plastic.

Before cooking, rinse rice/meat in filtered water to remove microplastics. (I know, does not prevent them from entering the water system but at least you are not eating them.)

Oppose fracking.

Buy from energy suppliers who do not frack if you can find one.

Store food in glass or stainless steel rather than plastic.

Buy more fruit and veggies fresh rather than packaged foods.

Save your produce plastic bags so you can take your own next time.

Support cleanup activities, like Clean Up Australia Day.

Soil

Buy organic where possible/feasible.

Avoid any food containing GMOs.

Buy and use a compost bin for your food waste.

Recycle your grass clippings.

Replace your lawn with a garden.

Grow your own herbs, fruit and veggies where possible.

Avoid chemical fertilizers, use natural alternatives.

If there is a community garden in your area, join it.

If you can, plant more trees personally or encourage others to do so.

Generally

Validate others doing the right thing.

Share stories that inspire and encourage others.

These steps are more or less realistic for most people and compound over time: one person’s changes inspire others, reduce demand on polluting systems, and directly protect local ecosystems that feed into global health.

And lastly, if you would like to help improve your home planet, feel free to share this article.

From your room mate on planet Earth,

Tom Grimshaw

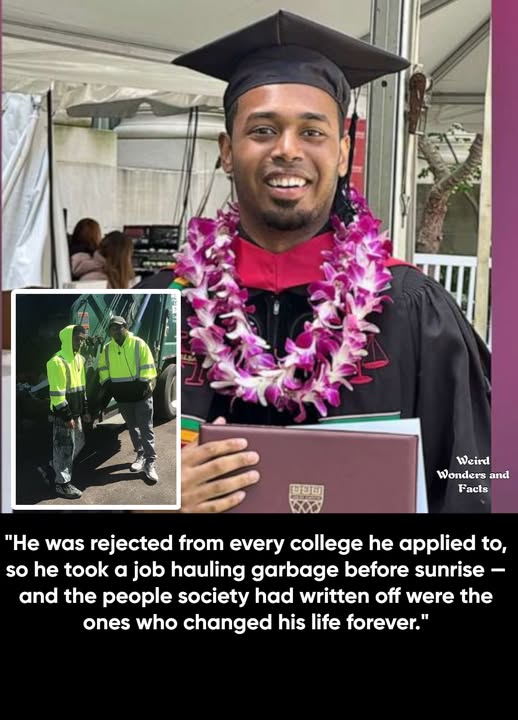

Rehan Staton

He was rejected from every college he applied to, so he took a job hauling garbage before sunrise — and the people society had written off were the ones who changed his life forever.

Until he was eight years old, Rehan Staton had a good life. He grew up in Bowie, Maryland, in a stable, middle-class home. He went to private school. He had two parents, a big brother named Reggie, and every reason to believe the future would be kind.

Then his mother left. She moved out of the country and didn’t come back.

Overnight, everything unraveled. Rehan’s father, now raising two boys alone, worked as many as three jobs at a time just to keep the lights on. Sometimes there wasn’t enough food. Sometimes the heat went out in winter, and Rehan slept in a heavy jacket because there was no other way to stay warm. His grades collapsed. The anger and hunger followed him into every classroom.

When a teacher suggested Rehan be placed in remedial classes, his father refused to accept it. He found an aerospace engineer at a local community center who offered to tutor Rehan for free. Within months, the boy was back on the honor roll. The teacher who had recommended remedial classes wrote his father an apology.

Rehan poured himself into boxing and martial arts through high school, winning national competitions and dreaming of going pro. Then, during his senior year, he suffered severe rotator cuff injuries in both shoulders. Without health insurance, physical therapy wasn’t an option. His path to professional sports was gone.

He scrambled to apply to colleges. Every single one rejected him.

So at eighteen years old, with no degree, no prospects, and a family struggling to survive, Rehan Staton took a job at Bates Trucking & Trash Removal. He collected garbage. He cleaned dumpsters. He started work before the sun came up.

Most of his co-workers were older men. Many were formerly incarcerated. Society had largely written them off. But these were the people who did something no teacher, no church leader, no guidance counselor had ever done for Rehan — they looked at him and saw potential.

They told him he was smart. They told him he was too young to be there. They said go to college, and if it doesn’t work out, this job will still be here.

It was the first time in his life that anyone outside his family had believed in him.

One of his co-workers connected him with the owner’s son, Brent Bates, who helped Rehan reach out to a professor at Bowie State University — a school that had previously rejected him. The professor was impressed and helped convince admissions to reverse their decision.

Then Rehan’s older brother Reggie made a decision that would alter the course of both their lives. Reggie was already enrolled at Bowie State. He saw the promise in his younger brother. And he dropped out of college so that Rehan could attend instead. Reggie went back to work to support their father and keep the family afloat — sacrificing his own education so his little brother could have a chance.

Rehan did not waste that chance.

He earned a 4.0 GPA. He transferred to the University of Maryland. He became president of the undergraduate history association, served on the dean’s cabinet, and was chosen as the commencement speaker for the class of 2018. The entire time, he kept working sanitation — waking before dawn to collect trash and clean dumpsters from 4 a.m. to 7 a.m., then rushing to class. Sometimes there was no time to shower between shifts, and he would sit in the back of the lecture hall in his yellow sanitation uniform, hoping no one would notice.

Then his father suffered a stroke. Rehan and Reggie both returned to work at the trash company to save their home and cover medical bills. Even then, Rehan didn’t stop. He graduated, took a job at a political consulting firm in Washington, D.C., studied for the LSAT, and applied to law schools.

He was accepted to the University of Southern California, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania, Pepperdine — and Harvard Law School.

When the news went viral, Rehan was uncomfortable with how the media framed it. The headlines all said the same thing: “Garbage Man Gets Into Harvard.” But that wasn’t the story he wanted to tell. He wasn’t self-made. He said so himself. His father worked three jobs. His brother gave up his own education. Sanitation workers — men the world had discarded — were the first to lift him up. A tutor volunteered his time for free. A professor fought to get him admitted. A co-worker’s boss opened a door.

Then filmmaker Tyler Perry saw the story and offered to pay Rehan’s tuition at Harvard.

At Harvard Law, Rehan didn’t forget where he came from. During his second year, he was walking to class and greeted a custodian in the hallway. The woman looked stunned and said she was sorry — she didn’t realize he was talking to her. Students, she said, usually looked at the wall rather than acknowledge her.

That moment stayed with him. Rehan used savings from his summer law firm job to buy gift cards for every custodian, food service worker, and support staffer at the law school. He wrote each one a handwritten thank-you note. And he founded an initiative called The Reciprocity Effect — an organization dedicated to recognizing and honoring the service workers who keep universities and institutions running but are too often invisible.

In May 2023, Rehan Staton graduated from Harvard Law School.

When reporters asked him about his journey, he didn’t talk about grit or willpower or pulling himself up by his bootstraps. He said something that cut straight to the truth of it all: “Although I get credit for working hard, working hard was the easy part because that I could control. I just happened to be around people who cared enough about me.”

Rehan Staton’s story isn’t really about one man beating the odds. It’s about what happens when the people the world overlooks — a struggling father, a selfless brother, a group of sanitation workers with criminal records — choose to believe in someone. And what happens when that someone spends the rest of his life making sure he never forgets it.

Not every hero wears a suit. Some of them wear yellow sanitation uniforms and start work before the sun comes up.

Success Rate