Now THIS is truth!

Except the spirit has no size and no position in space yet can conceive itself to be located.

Daily Job Moods At Work

When you really pay attention, everything is your teacher.

Funny iPhone Pic of Your Child

Stuck In Phone

A reminder that we are trying to free their minds from enslavement!

Celebrate today’s 200th anniversary of the birth of Australia’s greatest poet, Charles Harpur

With clowns to make our laws, and knaves

To rule us as of old,

In vain our soil is rich, in vain

‘Tis seamed with virgin gold!

But the present only yields us nought,

The future only lours,

Till we have a braver Manhood

In this Southern Land of Ours.

>From This Southern Land of Ours, by Charles Harpur (23 January 1813 – 10 June 1868)

Charles Harpur, Australia’s first national poet, but also philosopher, patriot, political activist and prophet, was born the second son of convict parents 200 years ago today on 23 January 2013 at Windsor on the Hawkesbury River.

Despite no mention of his bicentennial birthday on that supposed font of all knowledge, the internet, Harpur’s extraordinary and substantial collection of poetry, prose and philosophical writings are as pertinent and perhaps even more compelling today than they were when first published in the literary journals of the 19th century.

Given the proximity of his 200th birthday to the celebration of Australia Day, and that most Australians have no knowledge of this amazing forefather who felt called to be “the Bard of thy Country”, the CEC today pays tribute to Harpur’s life and legacy by introducing him to you, his fellow Australians.

In the mid-1800s Harpur and his poetry were synonymous with Australia coming of age and demanding its freedom and independence from the British Empire. In July 1826, the British sycophants at The Monitor newspaper in Sydney had written: “The people of New South Wales are a poor grovelling race… the scourge and the fetters and the dungeon and the Australian inquisition have reduced them to a level with the negro—they are no longer Britons, but Australians!” And a week later it reiterated that “they have lost their English spirit and have degenerated into Australians.”

Harpur was proud to be one such “degenerate Australian”, who like Robert Burns and other poets he greatly admired, including Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats and Poe, rejected the system of Empire and government of, for and by the oligarchs, in favour of the Republican ideal, that the common man had the potential to participate in his nation’s destiny, that he was the equal of the so-called upper classes and indeed that he was individually responsible for the future course of the nation.

Harpur also shared the vision of “freedom and independence for the golden lands of Australia” of the staunch republican Rev. Dr. John Dunmore Lang, saying of himself: “I am not only a democratic Republican in theory, but by every feeling of my nature. Its first principles lie rudimentally in the moral elements of my being, ready to flower forth and bear their proper fruit. Hence, as I hold myself, on the ground of God’s humanity, to be politically superior to no fellow being, so, on the same ground, I can feel myself inferior to none…”

Harpur maintained in fact that “the prime object of Society is, or should be, the perfection of Man” and all his important writings from early youth on, attempted, in one form or other, to nurture his fellow citizens’ “thinking power” as exemplified in the following stanza from his poem, Finality: “Why pile we stone on stone, to raise Jail, Fane, or Public Hall;—why plan Fortress or Tower for future days; Yet leave unbuilt, to wrong or guilt, The nobler pile—the Mind of Man.”

It worried Harpur deeply that “people are actually in danger of dying in their nobler part of sheer forgetfulness and want of mental stimuli” and he elaborated what he believed should be the aims and responsibilities of the true poet: “Her true vocation is at once to quicken, exalt and purify our nobler and more exquisite passions; and by informing the imagination with wisdom—suggesting beauty, both to enlarge and recompense our capacities of pathetic feeling and intellectual enjoyment, and further, in national and social regards, to illustrate whatever is virtuous in design, and glorify all that is noble in action; taking occasion also, at the same time, to pour the lightning of indignation upon everything that is mean and cowardly in the people, or tyrannical and corrupt in their rulers.”

Few Australian writers and poets of Harpur’s time, or since, could claim to have risen to his ideal. However, despite much disappointment in this regard, Harpur never relinquished his hope that one day, his vision of having a “nobler Manhood in this Southern Land of ours”, would be realised. He wrote: “At this moment I am a wanderer and a vagabond upon the face of my native Land—after having written upon its evergreen beauty strains of feeling and imagination which, I believe, ‘men will not willingly let die.’ But my countrymen, and the world, will yet know me better. I doubt not, indeed, but that I shall yet be held in honour both by them and by it.”

All Australians owe it to themselves as citizens, and to the memory of this great poet, to grant Harpur’s long-awaited hope by reading a selection of his truly beautiful and profound poetry on this day.

Click here to read more on the life and work of Charles Harpur.

Click herez for a selection of Charles Harpur’s poems.

To read more about Charles Harpur and the republican impulse in Australian history, click here for a free copy of the CEC’s pamphlet, From the First Fleet to the Year 2000: The Fight for an Australian Republic.

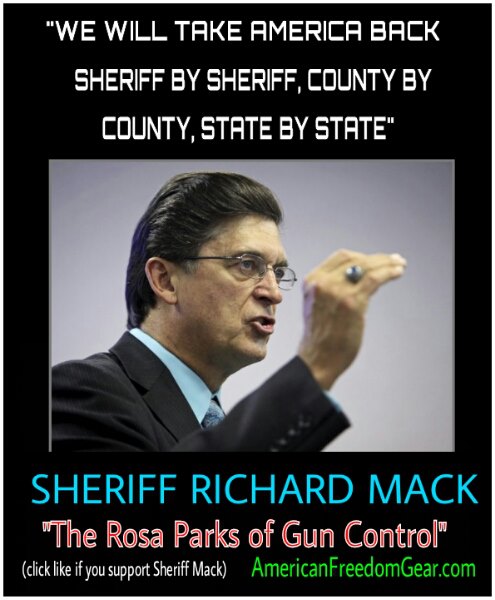

Power To The People

Sheriff Richard Mack

June 27, 1997 the Supreme Court decided that the federal govt has NO AUTHORITY to impose federal gun control laws on any US Sovereign State. Here is a great video of sheriff Mack teaching on States Rights https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TEFEnzQ_KPg

Liberty – From Spot On Ron Paul!

You are not responsible for your programming…

I wish you enough.

Recently, I overheard a mother and daughter in their last moments together at the airport as the daughter’s departure had been announced. Standing near the security gate, they hugged and the mother said:

“I love you and I wish you enough.”

The daughter replied, “Mom, our life together has been more than enough. Your love is all I ever needed. I wish you enough, too, Mom.” They kissed and the daughter left.

The mother walked over to the window where I sat. Standing there, I could see she wanted and needed to cry.

I tried not to intrude on her privacy but she welcomed me in by asking, “Did you ever say good-bye to someone knowing it would be forever?” “Yes, I have,” I replied. “Forgive me for asking but why is this a forever good-bye?”

“I am old and she lives so far away. I have challenges ahead and the reality is the next trip back will be for my funeral,” she said.

When you were saying good-bye, I heard you say, “I wish you enough.” May I ask what that means?”

She began to smile. “That’s a wish that has been handed down from other generations. My parents used to say it to everyone.” She paused a moment and looked up as if trying to remember it in detail and she smiled even more.

“When we said ‘I wish you enough’ we were wanting the other person to have a life filled with just enough good things to sustain them”. Then turning toward me, she shared the following, reciting it from memory,

“I wish you enough sun to keep your attitude bright.

I wish you enough rain to appreciate the sun more.

I wish you enough happiness to keep your spirit alive.

I wish you enough pain so that the smallest joys in life appear much bigger.

I wish you enough gain to satisfy your wanting.

I wish you enough loss to appreciate all that you possess.

I wish you enough hellos to get you through the final good-bye.”

She then began to cry and walked away.

They say it takes a minute to find a special person.

An hour to appreciate them.

A day to love them.

And an entire life to forget them.