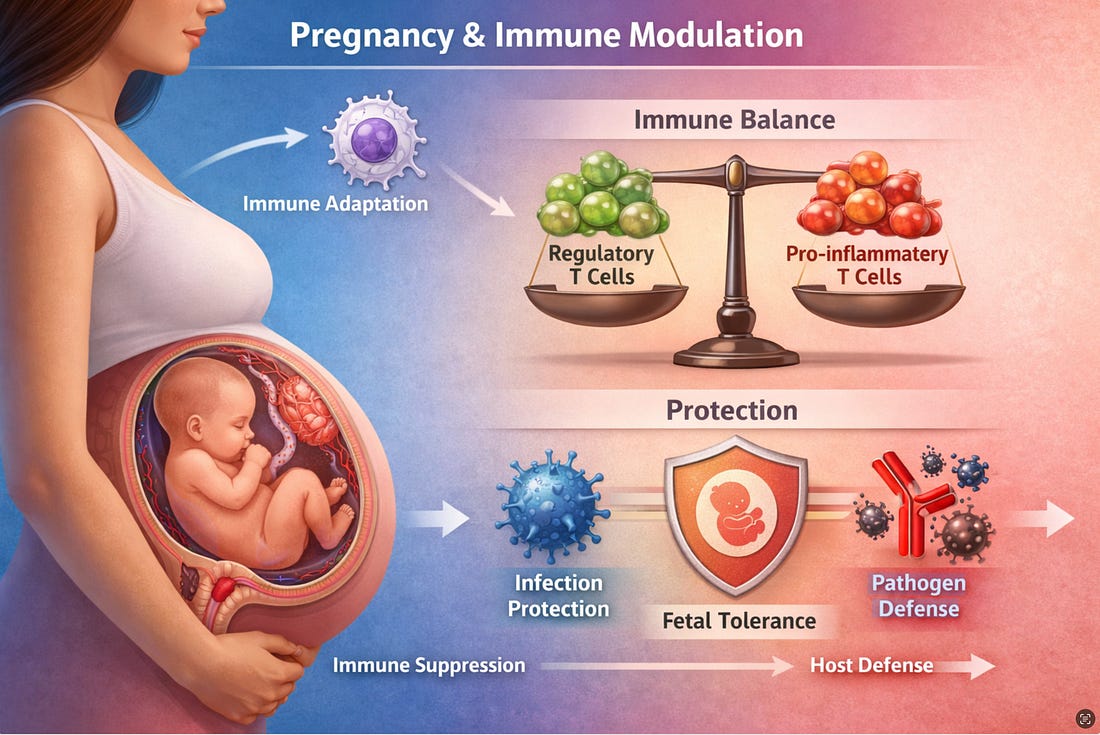

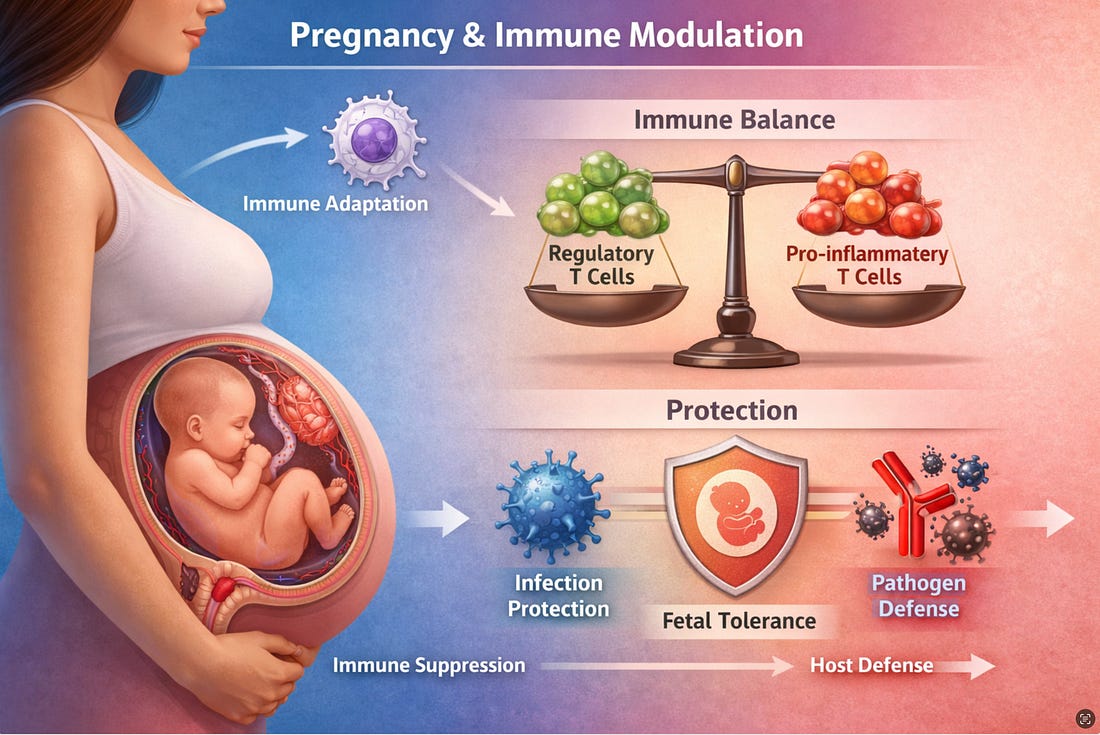

I had been told that a woman’s immune system “shuts down during pregnancy”. That is an incorrect oversimplification. The immune system does not shut down or reduce, it modulates its responses!

The claim that pregnancy “suppresses” the immune system has long served as a convenient shorthand for clinicians and public communicators alike. The reality documented in the scientific literature is considerably more sophisticated. Pregnancy does not weaken immunity in any straightforward sense; it recalibrates the immune system in ways that are both systemic and purposeful, with implications that extend well beyond the placental interface into how the pregnant body responds to pathogens and vaccines, and how the newborn is protected after birth.

Modulation, Not Suppression

The distinction between immune suppression and immune modulation is more than semantic. Multiple independent reviews have concluded that pregnancy reshapes the immune response rather than simply reducing it. As one widely cited synthesis states, the immune system during pregnancy is “not suppressed, but instead modulated to facilitate a pregnancy,” accounting for the differential susceptibility to different classes of pathogens observed across gestation.

This position is supported by large-scale longitudinal data. While there is little evidence for global immunosuppression during pregnancy, increased risks associated with certain viral infections reflect specific qualitative immunological changes rather than a general failure of host defense. The elevated severity seen with influenza, COVID-19, and hepatitis during pregnancy is attributable to targeted shifts in cellular immunity, not a wholesale reduction in immune function.

Those shifts are hormone-driven and body-wide. Estrogen, progesterone, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and cortisol each modulate specific immune components — cytokine profiles, NK cell behavior, regulatory T cell populations, and neutrophil activity — in ways that propagate systemically far beyond the uterus. A 2025 study from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai examining immunological transitions in uncomplicated pregnancies described dramatic changes in inflammatory mechanisms and immune cell dynamics when individuals transitioned from non-pregnant to pregnant states, with pre-pregnancy obesity further amplifying these inflammatory shifts.

Neutrophils illustrate the paradox well: they increase in number during pregnancy, but their reactive oxygen burst and cytokine responses post-stimulation are dampened — a state of being “primed but restrained.” Complement proteins such as C3a, C4a, and CH50 rise markedly, indicating that systemic inflammation is regulated rather than suppressed. These changes reflect a purposeful reconfiguration designed to sustain both maternal defense and fetal tolerance simultaneously.

The Placental-Systemic Feedback Loop

The local and systemic immune changes of pregnancy are not independent. The maternal-fetal interface is a unique immunological environment that balances fetal tolerance with pathogen defense, protecting both mother and fetus while preventing immune rejection of the genetically distinct fetus. Specialized local mechanisms — Hofbauer macrophages, decidual NK cells, and regulatory T cells accumulating in the decidua — create a tolerance-permissive microenvironment sustained by IL-10 and TGF-β secretion.

Critically, the hormonal signals driving these local adaptations propagate throughout the maternal circulation. This feedback loop between the placental microenvironment and the systemic compartment is why the immune changes of pregnancy cannot be understood in purely local terms. The pregnant woman’s response to a respiratory virus or to an intramuscular vaccine reflects ongoing immunological work to maintain the placenta, not merely a localized uterine adaptation.

Vaccine-Induced Immunity During Pregnancy: Functional Differences Exist

The modulated immune environment of pregnancy has measurable consequences for vaccine responses. A 2025 study published in npj Vaccines — part of the Nature Portfolio — examined serological and cellular responses to COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccines in pregnant and non-pregnant women and identified meaningful qualitative differences. Antibodies from pregnant women were less cross-reactive to non-vaccine antigens, including the XBB.1.5 and JN.1 variants. Non-pregnant women showed greater IgG1:IgG3 ratios and higher neutralization against all variants tested.

In contrast, pregnant women showed lower IgG1:IgG3 ratios and reduced neutralization breadth but demonstrated increased antibody-dependent NK cell cytokine production and neutrophil phagocytosis, especially against novel variants. The study also found that pregnancy increased memory CD4+ T cells, IFNγ production, and monofunctional dominance, and elevated fatty acid oxidation. This metabolic shift constrains B-cell and T-cell expansion and functional intensity, providing a plausible mechanistic basis for the observed differences in antibody quality.

This is not a picture of failed immunity. It is a picture of redirected immunity. The pregnant immune system compensates for narrowed antibody cross-reactivity by leaning more heavily on innate effector mechanisms. But from the perspective of protection against fast-mutating viruses, reduced cross-variant neutralization is a clinically meaningful limitation — one that routine titer comparisons in large immunogenicity studies may not capture. A 2025 systematic review in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, comparing the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant versus non-pregnant persons, similarly confirmed detectable and generally protective titers in pregnancy while noting the need for more mechanistic data on functional antibody quality.

These findings raise an open question in the literature: should vaccine formulations or dosing intervals be modified to account for the pregnancy-specific immune state? The available data do not settle this question, but they make a strong case for transparent, independent investigation.

Breast Milk: A Second Immune Transfer System

After birth, the infant faces its greatest pathogen exposure risk at mucosal surfaces — the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts — at a time when its own immune system is immature. Placental IgG transfer provides systemic coverage during the final trimester, but mucosal defense requires a different class of antibody. Breast milk addresses this gap, and the primary mechanism is secretory IgA (sIgA).

sIgA constitutes over 90% of immunoglobulins in mature human milk.8 When breast milk coats the infant’s oral mucosa, nasal cavity, Eustachian tubes, and gastrointestinal tract, sIgA binds pathogens at the surface before they can invade, keeping them immobilized for digestion and excretion rather than systemic entry. Critically, sIgA is stabilized by a secretory component that renders it highly resistant to digestive enzymes — a structural feature that IgG lacks — allowing it to remain functional throughout the infant’s gastrointestinal tract.

The sIgA content of breast milk is not generic. According to Brandtzaeg’s foundational work, the content of milk sIgA reflects the antigenic stimulation of the mother’s mucosal immune system by the intestinal and respiratory pathogens she has encountered.

Because mother and infant typically share an environment, this creates a personalized antibody repertoire calibrated to the specific pathogens the infant is most likely to face — a feature that formula cannot replicate.

Beyond immediate pathogen exclusion, breast milk sIgA plays a formative role in shaping the infant gut microbiome and regulating immune development. Experimental work in mice has shown that, in the absence of milk immunoglobulins, offspring develop natural IgA responses more rapidly, with premature germinal center reactions, suggesting that maternal sIgA actively modulates the pace and character of the infant’s immune maturation rather than simply substituting for it.

Natural Infection vs. Vaccination: A Difference in Milk Antibody Profile

A consistent finding across multiple studies is that the route of maternal antigen exposure determines the class of antibody predominating in breast milk. Natural infection — which stimulates mucosal immune tissues directly — generates an IgA-dominant milk antibody profile. Intramuscular vaccination, which acts primarily on systemic compartments, generates an IgG-dominant profile in milk.

This was documented explicitly in the context of COVID-19: mothers who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection had IgA-dominant antigen-specific antibodies in their breast milk, whereas mothers who received mRNA vaccines produced IgG-dominant responses in their milk.12 Whether breast milk IgG or sIgA provides more meaningful protection for the infant mucosal surface remains an active area of investigation.12 However, given that sIgA is structurally optimized for mucosal defense and enzymatic resistance, and given that influenza and pertussis vaccines administered during pregnancy have been shown to induce pathogen-specific sIgA and IgG in milk that protect breastfed infants from those respiratory illnesses,13 the route-of-exposure difference warrants continued study.

Conclusion

The scientific literature consistently supports one overarching conclusion: pregnancy represents a state of systemic immune recalibration, not suppression. The immune balance shifts from Th1-type proinflammatory activity toward Th2-type tolerance mechanisms; neutralizing antibody responses to novel antigens narrow, while innate effector pathways expand; and after delivery, breast milk provides a mucosal immune layer that is both personalized and only partially replicated by systemic vaccination.

Vaccines during pregnancy remain protective and are recommended — but the biological reality is more textured than institutional messaging typically conveys. Pregnant women generate detectable, functional immune responses to vaccines, while simultaneously operating under an immunological framework that prioritizes fetal tolerance, narrows cross-variant antibody breadth, and shapes infant mucosal immunity through a mechanism that intramuscular vaccines engage only incompletely. Understanding these distinctions is the reason to study it more rigorously, and to ensure that vaccine policy reflects the full complexity of the pregnant immune state rather than a simplified equivalence narrative.

Finish reading: https://open.substack.com/pub/rwmalonemd/p/pregnancy-and-immune-modulation