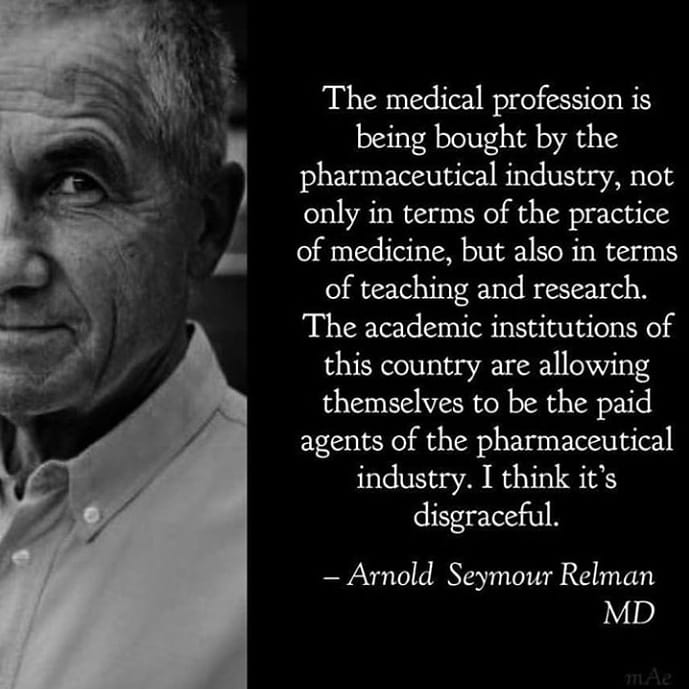

Medicine Bought By Pharma

Tom's Blog on Life and Livingness

Worth thinking about…

This isn’t going to change anyone’s mind but it may be of value in helping somone voice their thoughts.

If I held out a stick and said, “This is a stick.” few would disagree.

If I held out a rock and said, “This is a rock.” likewise, few would disagree.

If I held out a stick and said, “This is a rock.” most people would form the opinion that I was nuts. Because I was disagreeing with their reality. That has been the test of sanity these many years past. If you disagree with most people’s reality you are classed as insane. And reality is basically agreement.

A stick is not a rock. A rock is not a stick. Claiming a stick is a rock or a rock is stick is stating a lie. It is an insanity.

The Creator (or, if you don’t believe that, evolution) gave us two genders and only two genders. We were given them for a reason. Many reasons in fact. It takes one of each to make a pair. Pairs mate and we have successive generations. The species survives. It’s been very simple and has worked for man and beast since the game began.

Saying different does not change natural laws. Doing different does not change natural laws. If we had nothing but men pairing with men and women pairing with women the race would die out in a single generation. Therefore that is unworkable as an operating basis. Despite the loud protestations to the contrary of those who would violate the natural laws.

There is a legal principle that ignorance of the law is no defence. Ignorance offers no protection. That may very well have come from observation of natural laws. You can be ignorant of gravity and still fall to your death.

I posted a comment recently on FB to which someone asked my opinion, was it hopeless?

This was the guts of my response. I have added slightly to it.

I am currently asking myself the all important four word question (as well as discussing it with my daughter) “What will it take?”

To get vaccines from poisoning our children.

To get fluoride out of the water.

To stop destroying farmland for coal.

To stop destroying our aquifers for gas.

To stop the sell off of our farms, electricity and other assets to foreign nationals.

All of which I consider insane.

All these non-optimum conditions occur because someone gains from them.

The conclusion I have come to is nothing happens by chance.

Everything happens because it benefits someone – follow the money.

JFK said “There are no accidents in politics.”

I can see three reasons that politicians vote for these insanities. All require that they do not look for themselves.

I. They have been fed a steady stream of lies so they believe them.

Since it is hard to convince a man to change his mind when his livelihood depends on him maintaining his existing point of view and donations to political parties by corporations are allowed (let alone the guy who sold the port of Darwin to the Chinese is now employed by that company at a salary of $800,000 a year) then I do not believe putting the facts in front of our elected representatives will make much difference.

I beieve it will take educating and enlightening a sufficiently large enough group of active people so that the demand to change will overwhelming. That can take a long or a little time, depending on how effective we are at communicating the necessity to upset the status quo – which most are reluctant to embrace.

So anything you can do to “foward the message” in the way of reposting what I post, signing up for my newsletter (www.tlat.net) so you have those on file and can refer to them, seaching my blog (www.tomgrimshaw.com/tomsblog) or just engaging others in conversation adds to the movement.

If we do not stand up for our rights and defend our right to exercise them they will surely be eroded and we will be left without them.

Higher levels of urinary fluoride during pregnancy are associated with more ADHD-like symptoms in school-age children, according to University of Toronto and York University researchers. “Our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting that the growing fetal nervous system may be negatively affected by higher levels of fluoride exposure,” said Dr. Morteza Bashash, the study’s lead author and researcher at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

The drug companies are pushing world wide to have a monopoloy on “solutions” to your ills. If you do not want to be a “forever customer” on drugs, demand better and look for alternatives – nutrition, naturopathy, homeopathy, Chinese herbs, chiropractic to name a few. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/14/spain-plans-ban-alternative-medicine-health-centres