Below is ChatGPT’s analysis of the transcript of the interview. Many thanks to Shema Satya for directing ChatGPT to create this analysis:

ChatGPT’s Analysis of James Roguski’s Social Contract Interview:

Below is a full-map overview of what James covered, with his distinctive wording preserved as much as possible (and short, compliant quote fragments where it matters most).

Topic-by-topic map:

A) Money and payments: digital rails already exist; programmability is the next trap He tells the “plastic money” origin story: someone in a bar inventing credit cards to “skim 2–5% off the top,” once sounding insane but now normal. He says credit cards “create money out of nowhere,” most don’t grasp “what a racket… money is,” and money is “all digital… not yet programmable, but… pretty darn close.”

B) Government failure in crises + the “unspoken bond” among people: In disasters, he says agencies “get in the way” and “literally stop people from helping,” while ordinary people donate, show up, and rescue—because “we rely on each other” and government fails “when it’s most needed.”

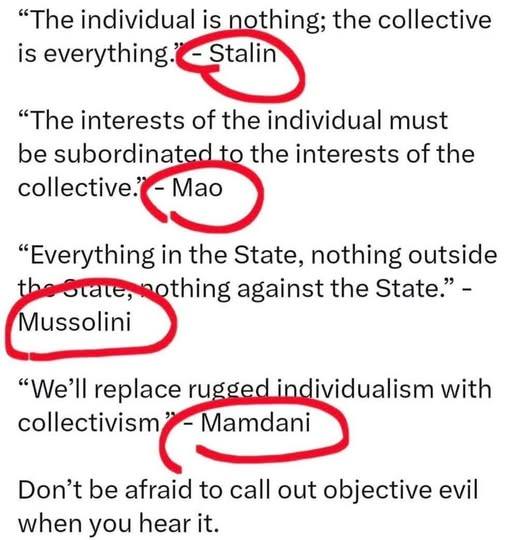

C) “Fascism” (his definition) and why swapping leaders won’t solve it: He rejects left/right framing and says the core is government + corporations colluding “at the expense of people.” “You’re not going to elect new people… the system is the problem.”

D) Religion and belief (brief but pointed): He says “belief is what you do when you don’t know,” and critiques outsourcing divinity to organized intermediaries vs finding it “inside of you.”

E) Education as training “slaves” vs producing creative, self-sufficient adults: He criticizes schooling as “bludgeoned in submission,” rewarding those who “submit and obey” to become “good slaves for the corporation or government,” contrasted with alternative education that yields a different adult—creative, self-sufficient, not preyed upon.

F) Thought, ideas, psyops, and tech mind-intrusion: He asks: “Where do you believe ideas come from?” and warns a “good idea” may be a “well- crafted psychological operation.” He brings in frequency/tuning analogies (radio/TV) and then the modern edge: Neuralink/sensors “tap into our thoughts… put thoughts into our minds.”

G) Capitalism / “isms”: He defines “capital” as “the means of production,” questions whether we want someone else to own it, says “anybody who is pro-capital… is anti-human,” while also rejecting communism/socialism/fascism—arguing we need something new that “doesn’t have a name.”

H) Decentralization as a general rule (with caveats): “When you centralize power you generally give up freedom,” and people with day-to-day control are “far happier than slaves.” He acknowledges the hard part: freedom can be abused; we need ways to stop abuse without turning society into a cage that provokes rebellion.

I) The PREPAct and “legalized criminality”: He says the PREP Act has “made criminal activity legal,” letting corporations “literally get away with murder,” protected from civil/criminal accountability.

J) “Too many laws” vs agreements: He contrasts Moses’ “10 rules” with modern scale: “hundreds of millions of words” of regulations—“no human being can comprehend that many rules.” His preference: “What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.”

K) Old ideas worth re-adopting + practical examples: He describes his “Garden of Eden” yard: 16–17 fruit trees, edible “weeds” (stinging nettle, mallow, dock, dandelion, lamb’s quarters, etc.), daily fruit/greens, and “Mother nature provides” seeds. He talks frugality (“waste not want not”) and refurbishing antique furniture left on curbs during COVID out-migration. He mentions mesh networks where devices relay communication—no single point a phone company can shut down.

L) Starving the beast: “stop feeding it” + build something better: He says the way out is easier when there’s “a better something to go to.” He explicitly calls out feeding propaganda via subscriptions (Netflix/Hulu) and feeding payment profiteers via credit cards: “Stop it.” But he warns: “the new systems are being built by the people who control the old system… tighter noose,” so alternatives must be independent.

Here is what he specifically means when he says “a social contract” / “a new social contract”:

1. Definition in plain terms (his phrasing): “A social contract… amongst each other, how do we agree to live with each other?”

2. Why it’s needed (his “problem statement”): Government has “morphed” into mind-control-by-representatives; if we’re “even talking about government, we’re barking up the wrong tree.” Our creations (government/corporations/nonprofits/religions) have “taken control of our lives,” and we “subjugate ourselves” by “signing contracts that give away our rights and freedoms.”

3. What it is not: Not “more government.” Not leader/follower dynamics: “don’t follow me, connect with me… It’s not leader and follower. It’s connection.” Not violent “burn it down” (he avoids advocating violence and notes violent revolutions often reinstall the same thing).

4. What it is aiming to replace (his target): “How do we want to deal with each other in a way that is different than government?” “We need… a different type of organized social contract.”

5. Scope: it applies to every domain (his list): He repeatedly lists domains: “money… health… education… communications… transportation” (and earlier, “personal health… money… communications… industry… business… work… every aspect of our life”).

6. Mechanism: build better parallel systems people choose (his “gravity” theory): If we create “a better system,” people “gravitate to it,” and the old system “withers and die[s] on the vine because we stop feeding the beast.”

7. His emphasis on legitimacy: “What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.” He points out most people never consented: “I didn’t agree to the constitution… It was agreed on your behalf.”

8. Where he’s putting it (his project): He says he’s working on “new social contract.com.”

Below is a “QUOTE BANK” built directly from the interview transcript“:

This quote bank shows something subtle but powerful: James never positions the social contract as ideology. He frames it as relational agreement, withdrawal of consent, and replacement by attraction.

“A social contract is really just how do we agree to live with each other.”

“The real question is not government — it’s how do we want to deal with each other in a way that is different than government.”

“What we actually need is a different type of organized social contract.”

“What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.”

“We’ve lost sight of the will of the people — by the people that we hire to work for us.”

“Sometimes you look at a building and say, this thing is decrepit and needs to be torn down.”

“If we’re even talking about government, we’re barking up the wrong tree.”

“We have created systems, and now we are subjugating ourselves to those systems.”

“You submit yourself to their authority by signing some kind of an agreement.”

“You give up all of your rights — maybe unknowingly.”

“I didn’t agree to the Constitution. It was agreed to on my behalf.”

“We didn’t sign up for this — we inherited it.”

“The actual beast system is already in place.”

“What if the Antichrist is not a person — what if it’s the system?”

“The ’they’ that everyone talks about is the hierarchy enslaving you.”

“AI and CBDCs are not the beast — they’re an adjunct to the system.”

“Fascism is government supporting corporations at the expense of the people.”

“It doesn’t matter if it’s left or right — the system is the problem.”

“You’re not going to fix this by electing different people.”

“Health and healthcare are not rights — the right is the right to decide.”

“Public health is a joke.”

“Symptoms are the lights on the dashboard.”

“Drugs don’t fix the problem — they just suppress the warning lights.”

“The World Health Organization has morphed into the marketing arm of the pharmaceutical cartel.”

“When I hear PHEIC, I think pharmaceutical hospital emergency industrial complex.”

“This is a cartel, not public health.”

“There are hundreds of millions of words in laws and regulations.”

“No human being can comprehend that many rules.”

“What works is agreements between people.”

“When you centralize power, you give up freedom.”

“People who control their day-to-day lives are far happier than slaves.”

“The system only exists because we keep feeding it.”

“If we build something better, people will gravitate to it.”

“The old system doesn’t need to be destroyed — it withers when we stop feeding it.”

“Don’t follow me — connect with me.”

“This is not leader and follower — this is connection.”

“Social Contract Principles”

Here is a distillation into 10 “Social Contract Principles”, written in James Roguski’s language and cadence, not polished into ideology, not softened, and not generalized. Think of these as load-bearing beams of his worldview.

1. We agree with each other — not rule over each other

“A social contract is how we agree to live with each other.”

The foundation is not authority, hierarchy, or rule-by-proxy.

It is direct agreement between people about how they will coexist.

2. Government is not the solution — it is the wrong question

“If we’re talking about government, we’re barking up the wrong tree.”

The social contract is not about fixing government, reforming it, or electing better managers.

It exists outside government.

3. Agreements create legitimacy — not laws

“What you need are agreements amongst people to live together.”

Millions of pages of laws do not create order.

Voluntary agreements do.

4. Consent must be explicit — not assumed

“I didn’t agree to this. It was agreed to on my behalf.”

Systems that operate without clear, conscious consent have no moral authority.

Inheritance is not consent.

5. What we create must never control us

“Whoever creates something should never be controlled by the thing they created.”

Governments, corporations, institutions, and technologies exist to serve people —

the moment they reverse that relationship, the social contract is broken.

6. Power must decentralize or freedom disappears

“When you centralize power, you give up freedom.”

Centralization always concentrates control.

Decentralization restores dignity, autonomy, and responsibility.

7. Fascism is the fusion of government and corporations

“Government supporting corporations at the expense of the people — that’s fascism.”

The social contract explicitly rejects cartel systems disguised as public good.

8. Rights are not permissions — responsibility comes first

“Health isn’t a right. The right is the right to decide.”

The social contract places responsibility back in the individual —

not outsourced to experts, authorities, or institutions.

9. The system survives only because we feed it

“The beast only exists because we keep feeding it.”

Compliance, subscriptions, dependency, and convenience are its fuel.

Withdrawal of participation is non-violent power.

10. The old system dies by replacement, not destruction

“If we build something better, people will gravitate to it.”

Revolutions recreate cages.

Parallel systems dissolve them.

A Social Contract for Free People Based on Agreement, Consent, and Human Dignity:

James’s social contract is not utopian, ideological, or authoritarian. It’s pragmatic, relational, and grounded in consent and withdrawal rather than force, building parallel, living systems rather than fighting collapsing ones.

We do not seek to fix the old system.

We choose to outgrow it.

This social contract is not granted by government, enforced by authority, or mediated by institutions. It arises from agreement among people who choose to live together with clarity, responsibility, and respect.

1. We agree with each other — not rule over each other

• Our relationship is networked, not hierarchical.

• No one stands above another by virtue of title, position, or permission.

• We organize our lives through direct agreement, not domination.

2. Government is not the foundation of social order

• We reject the assumption that government is the natural or necessary source of legitimacy.

• If the question begins with “what should government do,” the question is already misframed.

• Social order begins with people — not institutions.

3. Legitimacy comes from consent, not inheritance

• No system has authority over us simply because it existed before we were born.

• Agreements made on our behalf without our consent do not bind us morally.

• Consent must be conscious, explicit, and revocable.

4. Agreements matter more than laws

• No human can comprehend millions of pages of rules.

• Law without consent becomes coercion.

• We choose clear agreements between people over endless regulation imposed from above.

5. What we create must never control us

• Governments, corporations, technologies, and institutions are tools — not masters.

• The moment our creations dictate our lives, the social contract has been violated.

• People come first. Always.

6. Power must remain decentralized

• Centralized power erodes freedom and responsibility.

• Decentralized power restores dignity, creativity, and self-determination.

• We choose systems that distribute control, not concentrate it.

7. The fusion of corporate and governmental power is illegitimate

• When government serves corporations at the expense of people, it ceases to be public service.

• Cartel systems disguised as “public good” are rejected.

• Profit does not override human life, health, or liberty.

8. Responsibility precedes rights

• True freedom begins with responsibility for one’s own body, life, and choices.

• No authority can replace personal responsibility without diminishing humanity.

• The fundamental right is the right to decide.

9. Systems persist only because people feed them

• No system survives without participation.

• Compliance, dependency, and convenience are its fuel.

• Withdrawal of consent is non-violent power.

10. We replace what no longer serves us

• We do not burn down the old world.

• We build something better and let the old wither from neglect.

• People naturally gravitate toward systems that honor life, choice, and coherence.

Ten Principles for a New Social Contract

(In the spirit of James Roguski)

1. We choose how we live together

A real social contract begins with a simple question: How do we agree to live with one another?

• Not through force.

• Not through authority.

• Through conscious agreement.

2. Government is not the starting point

• If every solution begins with government, we’re already lost.

• Order doesn’t come from institutions.

• It comes from people choosing responsibility, cooperation, and clarity with one another.

3. Consent matters — inherited systems do not equal agreement

• Most of us never agreed to the systems that govern our lives.

• They were decided for us, not by us.

• A legitimate social contract requires real consent, not assumptions.

4. Agreements work better than endless rules

• No human can understand millions of pages of laws and regulations.

• But people can understand clear agreements with one another.

• When rules replace relationships, something essential is lost.

5. What we create should never control us

• Governments, corporations, technologies, and institutions are tools.

• They exist to serve human life — not to dominate it.

• When our creations begin to dictate our choices, the contract is broken.

6. Centralized power erodes freedom. History is clear:

• The more power is centralized, the less freedom remains.

• Decentralized systems restore dignity, creativity, and personal responsibility.

7. Corporate power disguised as public good is not legitimate

• When government serves corporations instead of people, it stops serving the public.

• Systems that prioritize profit over life, health, and freedom deserve to be questioned — and withdrawn from.

8. Responsibility comes before rights

• Freedom is not something granted by authority.

• It begins with taking responsibility for one’s own body, choices, and life.

• The most fundamental right is the right to decide.

9. Systems survive only because we participate in them

• No system has power without our energy.

• Our attention, money, compliance, and dependence keep old structures alive.

• Withdrawing participation is a peaceful and powerful act.

10. The future is built, not overthrown

• We don’t need to destroy the old world.

• We need to outgrow it.

• When something better exists, people naturally move toward it — and what no longer serves quietly fades away.

Closing Declaration

This social contract is NOT an ideology.

It is NOT a movement to follow.

It is NOT a leader to obey.

It is an invitation…

• to connect with each other

• to consciously choose how we live together,

• to reclaim responsibility,

• and to build parallel systems rooted in consent, not control.

We are NOT subjects.

We are equals.

Moving forward into the future, we must choose and act accordingly.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jamesroguski/p/jerm-warfare