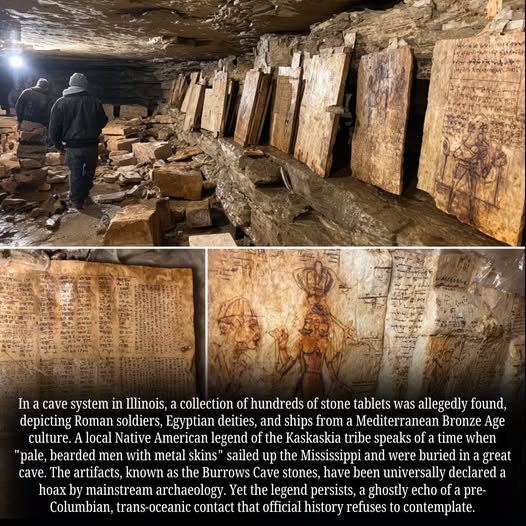

Pfizer Knew Jab Damages Reproductive Organs

Leaked internal Pfizer documents have revealed a disturbing truth: the vaccine’s greatest impact may not be on the lungs, but on the future of human reproduction. Instead of primarily targeting the respiratory system, the data shows an obsessive focus on the organs of fertility—particularly those that define masculinity itself.

https://thepeoplesvoice.tv/pfizer-mrna-nanoparticles-boys-damaging-masculinity-fertility/

Purposeful Eating

We all eat with a purpose. Most people eat with the purpose of satisfying hunger and taste.

Eating with that purpose results in most of us living the last 50 years of our lives suffering more and more symptoms and diseases, less energy and more senior moments.

There is an alternative – eating with a higher purpose: Eating with the purpose to fully satisfy nutritional and energy requirements in order to maintain long-term health.

If you need help on improving your eating, reach out to me.

COVID-19 “Vaccines” Reduce Life Expectancy by 37%

Alessandria et al followed 290,000+ people for years and found that two mRNA shots resulted in a 37% loss of survival time compared to the unvaccinated during follow-up. This isn’t public health—it’s population sabotage.

Click to view the video: https://x.com/NicHulscher/status/1965041283736461770

Australia: 18 people who took the same batch of Covid injection have all developed cancer.

Panini Grammar

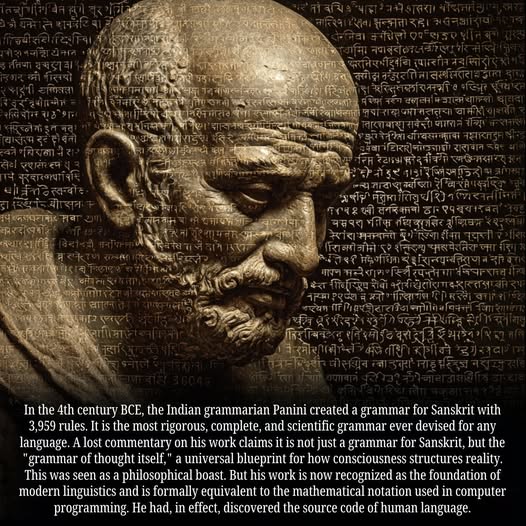

The Dreamtime as a Geological Record

How to tell if the honey you purchased really came from bees

The honey will naturally form a honeycomb pattern based on ‘memory’ if rinsed with water. Click to view the video:

Video calls every vaccine into question

President Donald J. Trump on Monday posted a video to Truth Social featuring doctors warning about thimerosal in vaccines and tying mercury exposure to neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism.

Watch the video: https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/posts/115169661443239054

Parents Of Vaccine Injured Kids Speak Out

Pediatricians typically earn $200–$600 per fully vaccinated patient, with some making more than $1 million annually.

Click to view the video: https://x.com/redpilldispensr/status/1964962837433856272